Dr Rachel Buchanan (Taranaki, Te Ātiawa) is an author, historian, archivist, journalist and curator. Her recent book Te Motonui Epa (Bridget Williams Books, 2022) tells the story of a treasured set of carved pātaka (storehouse) panels that were smuggled out of the country in the 1970’s.

When they resurfaced at a Sotheby’s auction years later it prompted a long and complicated process to bring them home again. It is a compelling story that involves skullduggery and theft and greed and it is written with the eye of a writer who thinks like a poet. We asked her some questions about her work.

Read the full WOMAN+ interview about Te Motonui Epa here.

On the eve of the apocalypse, the old people hid the treasure. They said karakia to ward off the terror and panic. Clear heads, steady hands, quick feet, teamwork, a plan. Future-proofing. They dismantled the pātaka and carried the five carved panels to Peropero, a swamp just north of Waitara. They placed the taonga in the gentle arms of mother Earth. The rangatira carved into the tōtara took one last look at the blistering Taranaki sky before they let go, sank beneath the surface and went to sleep. Power-save mode was fully activated. Snug and safe, our tūpuna dozed in the dark beneath the days and months and years of the 1820s and 1830s when Taranaki was gutted by invaders from the north.

They were waiting for someone to come back to get them, but no one did. The ones who had hidden the epa were killed or captured or had fled. Then, just as people began to return home to Taranaki, a new apocalypse began. The first shots in the war between Taranaki and Britain were fired on 17 March 1860 at Te Kōhia pā, just down the road from where the carvings lay. From there the fighting spread south, along the coast and inland, encompassing the whole province.

He rā pōuri, he rā tukupū pōuri kerekere.

These are days of darkness and the moon and stars give no light.

The hiding place at Motunui was forgotten. The soil shifted and the place markers sank. The temporary interment of the panels stretched into something more permanent. The epa were left alone, and the years became decades and the decades became a century and then the century became a century and a half. The carvings travelled on, unchanged, beneath the surface of time – not dead, not extinct, but dormant.

The problem was, the epa were hōhā. It was boring down there in the dark. It was lonely. And they were sick of being in the one spot. They wanted to have a look around – do something! So, our ancestors stretched their tongues, rolled their eyes and got ready to wake up.

The old world was about to meet the new.

The alarm clock went off in late 1971. Summer. Cicadas owned the airwaves. And cows. And the sea. If you lived near the coast, the sea hummed all night like a giant air-conditioning unit.

Cecil Smart, a Pākehā farmer, contracted Alec Fields of Inglewood to dig a ditch through the swamp opposite the Bailey house on Otaraoa Road, Tikorangi. Cecil and his brother Maurice ran drystock there. Thirteen years earlier, the brothers had leased the land from the Māori owners, the Skipper family. The block was known as Ngatirahiri 1D2.

The digger got to work, and in doing so scraped the edge of a buried length of wood, shearing off some of its carved surface.

Speckles of light at first, then a stream, then a flood. The air was a shocking blast of salty cool on our ancestors.

Cecil Smart was aware that Māori artefacts, as he called them, had been found nearby. A carved panel had been discovered there by local man Percy Cole in 1958. When Fields had finished his work and the whole ditch had been dug, Cecil contacted an acquaintance, Melville Manukonga, to see if he would like to come and have a look around. Manukonga, himself a carver, was the owner of Kurahaupo, a souvenir shop in New Plymouth. He sold his own work there and at other places, like the shop at Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Cecil showed him the spot where the digger had scraped the carving. Manukonga walked around, felt the carving with his foot, and bent down to examine it. Our tūpuna looked up at him. They blinked. They were so happy to be found, touched. Then Manukonga made a wider, more careful search. In the sides of the drain he saw four more carved panels, which, when placed together, formed the complete wall of a pātaka or food store. He also found two other pieces of carved wood, the bits that had been removed from the first panel by the blade of the drain digger.

Manukonga had found the odd stone sinker or broken adze before, but nothing as exciting as the panels. ‘It was like a gold prospector finding gold,’ he later said.

Cecil and Manukonga took the carvings back to Cecil’s place. They washed them, then Manukonga covered them in wet sacks and, with Cecil’s consent, took them back to his house at Constance Street, New Plymouth. He cleaned them again, treated them with a mixture of kerosene and linseed oil, and stored them in his shed. From then on, he regarded the panels as his property. Finders keepers, as they say.

Cecil’s brother Maurice Smart was away fishing when the panels were unearthed, but a few days after he got back he went over to Manukonga’s place to have a look at them. The carvings were in a very bad state. ‘As I say, they looked a mess,’ Maurice recalled. ‘When I saw the wood under the wet sacks I didn’t think they had any real value. All I thought at the time was that Mel Manukonga would be lucky to save them.’

Manukonga knew the carvings were very significant. He appreciated the exquisite skill in the strokes, the hours and days and months it would have taken to bring the figures to life from the fine red pine, the restraint and patience of the artists. He judged that one panel had been made with greenstone tools, because the markings were shallower. This panel had possibly been made for a maihi, a gable of a meeting house, and it was almost certainly made in pre-European times, though it may have been modified to fit with the newer work. Those other panels, with their deep, intertwined serpentine figures, had probably been carved with steel – early on, well before 1840. He took some photos of the panels with his Box Brownie and started to invite ‘interested people’ to his shed for viewings. Among them were Audrey Gale, the chairwoman of the Taranaki Museum Board executive committee, and her husband. The aim, Manukonga would later say, was to present the taonga to the Taranaki Museum.

On 26 August 1972, Audrey Gale made her second visit to Constance Street to see the epa. This time she was accompanied by New Plymouth-born anthropologist Dr Harry Skinner, founder of the New Zealand Archaeological Association and a former director of the Otago Museum. The carvings were now laid out in the living room, each set apart from the other. Put together, they were about 1.5 metres high at the peak of the middle panel and 1.2 metres wide – about the same size as the side of a small car. The anthropologist and the museum board chairwoman tiptoed around the panels for about three-quarters of an hour, then left.

Manukonga had also invited the director of the Taranaki Museum, Rigby Allan, but he did not turn up. Manukonga was so offended that he decided he would not present the panels to the museum after all. Instead, given the ‘complete lack of interest shown by Mr Rigby Allan’, he would mount them in his home. He later told Nigel Prickett, an archaeologist and former curator at the Taranaki Museum, that he heard Rigby Allan had gone to play bowls instead.

Some five months later, on 11 February 1973, Andrew Moller, a retired dairy factory manager from Edgecumbe, and his wife Margaret took Canadian visitors Mr and Mrs Jack Binkley to Manukonga’s house to view an assortment of his carvings. The men had become friends during the Second World War; Moller bought the Binkleys a wooden tiki as a gift.

Manukonga took the two couples out to the shed to show them the epa. Andrew Moller was impressed. As a member of the Bay of Plenty Historical Society, he knew a bit about ancient Māori carvings, and recognised that the panels were carved in ‘traditional Taranaki style’ and had been part of the end wall of a pātaka. Manukonga let him take a photograph, and Moller later passed this on to the curator at Whakatāne Museum.

On another occasion, Manukonga invited a local collector, Raymond Joseph Watenburg of Waitara, to value the panels. Watenburg believed the carving on the farthest left of the five panels was made by carvers associated with Manukorihi pā, Waitara. The other four he categorised as coming from ‘Ngatirahiri’. He later recalled that while he was looking at the panels, a man and woman arrived and asked him if he thought the panels were genuine. Watenburg said he thought they were, and that he estimated their worth at about $14,000. He also told them the carvings couldn’t go out of the country; the couple said they were setting up a collection on the East Coast. That night, Watenburg invited the pair over to his place to look at his collection, but they seemed unimpressed. The man did most of the talking. He was European. The woman was nondescript.

Melville Manukonga did not mention Raymond Watenburg at all in the account he later gave to investigators. The way he recalled it, a man and woman showed up unannounced at Constance Street one weekend afternoon in late February 1973. He had ‘no idea’ how they had heard about the carvings, as few people knew of their existence. The man was in his early thirties and spoke with an educated English accent. The woman was about the same age but she had an American accent. They drove a new car, something like an Austin Maxi. The woman told Manukonga that her father was a millionaire. They said they were travelling around New Zealand buying artefacts and had heard he had some carvings. They asked to have a look.

The epa were face to face now with a different kind of connoisseur, one whose networks extended well beyond Pākehā scholars, museum staff, fossickers and members of local historical societies, and out into the world of international dealers and collectors for whom discernment and discretion were the code words that hid other motives. Money was one motive, obviously. But there were other things too – about possession and protection, hoarding and storing, a sort of mooning sentimentality about the lost, the dead, the former, the primitive, the pure, the true.

The man and woman touched our ancestors’ faces and bodies, making a careful appraisal. They were clearly interested, and questioned Manukonga closely. He showed the couple specific parts of the panels that were particularly characteristic of Taranaki carving. Number one: the foreheads of the faces were pointed, like the summit of a mountain. When the panels were placed side by side, they also formed a mountain shape. That was one of the major giveaways. The writhing, serpentine figures cut so deeply into the wood were another Taranaki signature. As were the short, curved ridges that cut into the patterns on the eyebrows or mouths of the figures, and the open loops and spirals above the heads.

Scholars had written – and would continue to write – about these features, noting the various details and publishing articles about them in the Journal of the Polynesian Society and elsewhere. John Yaldwyn, director of the National Museum, Wellington: ‘As a style, Taranaki carving has not been followed since the musket wars of the early nineteenth century.’ The skill and rarity of Taranaki work was remarkable. Past tense: mandatory. Tone: final. Stone-age Taranaki Māori art.

Now, an exhumation, a pulse, heartbeat, colour. A glowing miniature of the mountain on the lounge-room floor.

Touched, the figures looked startled, puckered, wrinkled, quizzical, intertwined, like birds or serpents trapped in wood. The arms and legs flowed in and out of each other, and in the central panel, a three-fingered hand reached out of a mouth.

‘Ancestor sculpture with the interwoven bodies possibly sexual in significance expressing ideas of fertility and abundance (a theme not inappropriate to a food store-house!)’

Like a strand of DNA made from wood. A double helix with tongues. Like eels seething in a black creek.

An encyclopedia in another language.

An index finger, pointing to the future and the past. Look!

Taonga tuku iho.

The epa watched the three people from many angles. Their eyes, where pāua shells once hung, were little knobbles in the wood, like buttons. They scanned the people’s faces. The man and woman were keen but not too keen. Nonchalance was a good mask. Melville Manukonga was hopeful, wary.

The man asked Manukonga if he was interested in selling the panels, and Manukonga said he was not. The man asked him to think about it and said he would contact him again.

Two or three days later, the man once again got in touch. He offered to buy the panels for $6,000. The average annual income in New Zealand at that time was less than $5,000. Manukonga and his wife Frances talked it over and decided to sell. The next day the man and woman came back. The man wrapped the panels in sacking and put them in the boot of his car. They paid Manukonga in cash, as per his request. ‘Whilst I counted the money I asked the two persons whether they intended to take the said panels out of New Zealand and they assured me they did not,’ he would later recall.

Several weeks later, the epa left New Zealand. How? The dimensions were one restriction on concealment. Height x width x depth, 1050–680 x 440 x 50mm. And the weight. The carvings could not be fitted in your carry-on or squashed into a sports bag. One theory was that the epa were painted red and smuggled out disguised as replicas. Another was that our tūpuna were hidden in the back of a wardrobe.

By April, the epa were in an apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side owned by Roberta (Bobbie) Nochimson, an historian and collector of Pacific art. The touching continued. The looking. The calculating. The telephone calls to interested parties. Swiss-based collector George Ortiz flew in to New York for a viewing.

The epa met him on 21 April 1973. They let their eyes bore into him. Then they made their eyes pop at him, pūkana style. Then they shrugged. What now, wee fellow?

George Ortiz was not much taller than the highest panel. One of his famous friends, British writer Bruce Chatwin, called him Mighty Mouse. He was a dapper dresser, with dark eyes, dark skin and a cap of black hair. He was also the possessor of an eighteenth-century mansion in Geneva and an ebullient, obsessive spirit – and primed to appreciate this masterpiece of Taranaki art. Ortiz prided himself on his eye, his gift, the way he could perceive what artists had put into their work.

Our tūpuna, so complex and beautiful, hit him with an incredible force. His response was emotional, visceral and instantaneous. It was FOMO at an epic scale. Two days later, George Ortiz agreed to a purchase price of US$65,000, to be paid in three instalments. A sort of Afterpay arrangement, with a little bit knocked off the price if he promised to throw in ‘a few minor items’ in return. The vendor admitted he had removed the carvings from New Zealand without a permit – but even so, he was still the owner, he held the title and he would pass that title on. Ask me no questions, I’ll tell you no lies. All in good faith.

They called it primitive art. Or Oceanic art, to be nice.

By 11 May 1973, our tūpuna were on a plane to Switzerland. From six feet under to 30,000 feet up, Taranaki’s envoy had been dispatched.

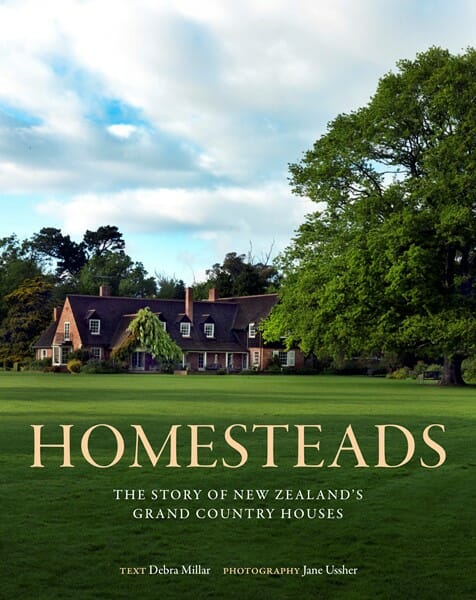

Imagery from: Rebecca McMillan