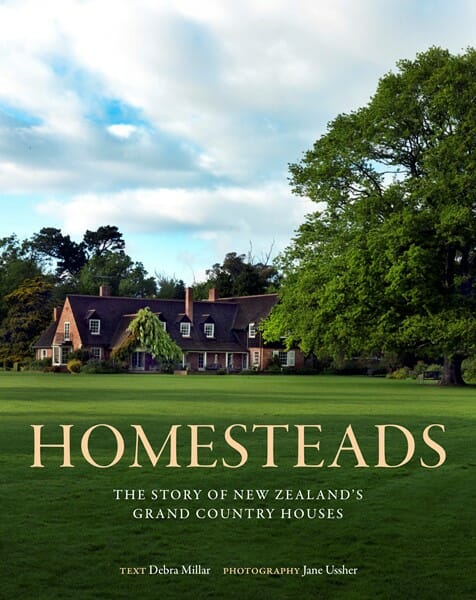

Photography by Jane Ussher. Words by Debra Miller

Men figure prominently in the stories of most station homesteads. But the house built at Merchiston Station between 1906 and 1908 was the ambitious vision of Edith Hammond (née McKelvie).

Edith oversaw the design and construction of the 34-room homestead at Rātā, just south of Hunterville, and personally selected many of the finishes and fittings used in the house.

The New Zealand International Exhibition, which was held in Hagley Park in Christchurch from November 1906 to April 1907, undoubtedly fuelled many of her ideas. The architect she chose, Joseph Clarkson Maddison, was responsible for the design of the temporary exhibition buildings, and an ornate Italian Renaissance-style fountain that stands on the driveway in front of the homestead was originally displayed outside the entrance to the exhibition’s main hall. The carved Oamaru stone fountain was made by a Christchurch stonemason, John Hunter of Colombo Street, as ‘an advertisement for New Zealand craftsmanship and for the use of Oamaru stone’. After the exhibition closed and the Hagley Park buildings were dismantled, Edith purchased the fountain for £30 and had it transported to Merchiston. It had cost £265 when commissioned.

Edith’s impressive three-year building project was underwritten by an inheritance from the estate of her father, John McKelvie — one of Manawatū’s pioneering station owners. Her husband, John Hammond, also hailed from prominent Rangitīkei farming stock, and when he and Edith married it was said to bring together two ‘of the oldest, wealthiest and most esteemed families in Rangitikei’.

The couple were living in a single-storey homestead at Merchiston when Edith ‘decided to build the house she had been dreaming of ’ and commissioned Maddison’s grand design. The original homestead, located just behind, burnt down while its replacement was under construction.

The initial budget for the build was £5000, but on completion it is believed to have cost almost three times that amount. Edith refuted this, however; an article in the Hunterville Express reported: ‘The description of the design of the structure is misleading, and the price, as stated — £10,000 — is incorrect.’

Despite the rising costs, Edith ‘refused to lower her standards’ and sent frequent telegrams to Maddison refining the design, via the on-site clerk of works. According to a Hammond family history, ‘Credit for the design and for the standard of the construction goes to Edith herself. She watched over every step in the building of the house, and checked out each feature of furnishing and decoration.’

As an example of her attention to detail, while there are 23 fireplaces in the house — resulting in two men being employed full-time at the station to cut firewood in Edith’s day — no two fireplaces have the same tile surround or mantelpiece decoration. Each bedroom has a unique cornice detail.

Richard Rowe, Edith’s great-grandson, lives there today with his wife, Vicki. He suggests that Edith’s approach to the house was heavily influenced by the unprecedented array of materials and decorative finishes she encountered at the Christchurch exhibition.

Maddison’s design includes a number of unusual features that add to the house’s striking appearance. An open-air belvedere, which contains a bell from John Hammond’s family home, York Farm, which was located on the banks of the Rangitīkei River, provides a sweeping view of the garden and farm. It occasionally comes to life when Richard and Vicki’s son William, a New Zealand champion bagpiper, plays from there. A turret reached via a narrow set of stairs at the western end of the house once served as a wardrobe where Edith Hammond’s best clothes were stored.

But perhaps the most distinguishing feature of Maddison’s design is the absence of a soaring entrance hall. Instead, there are three entry points to the house from the wide verandah that wraps around its east, west and south sides. There was no servants’ accommodation within the house: at the time it was built, domestic staff were housed separately on site, and this dispensed with the conventional arrangement of a grand staircase used by family and a narrow staircase for servants sequestered at the rear of the house. As a result, rooms open onto a central hall that forms the main circulation space. Laid out in a square plan form, it has an 8-metre stud height and is dominated by a massive staircase with banisters carved by Ngāti Hauiti craftsmen. In upstairs bedrooms, internal windows to the second-floor gallery increase the amount of natural light in the centre of the house.

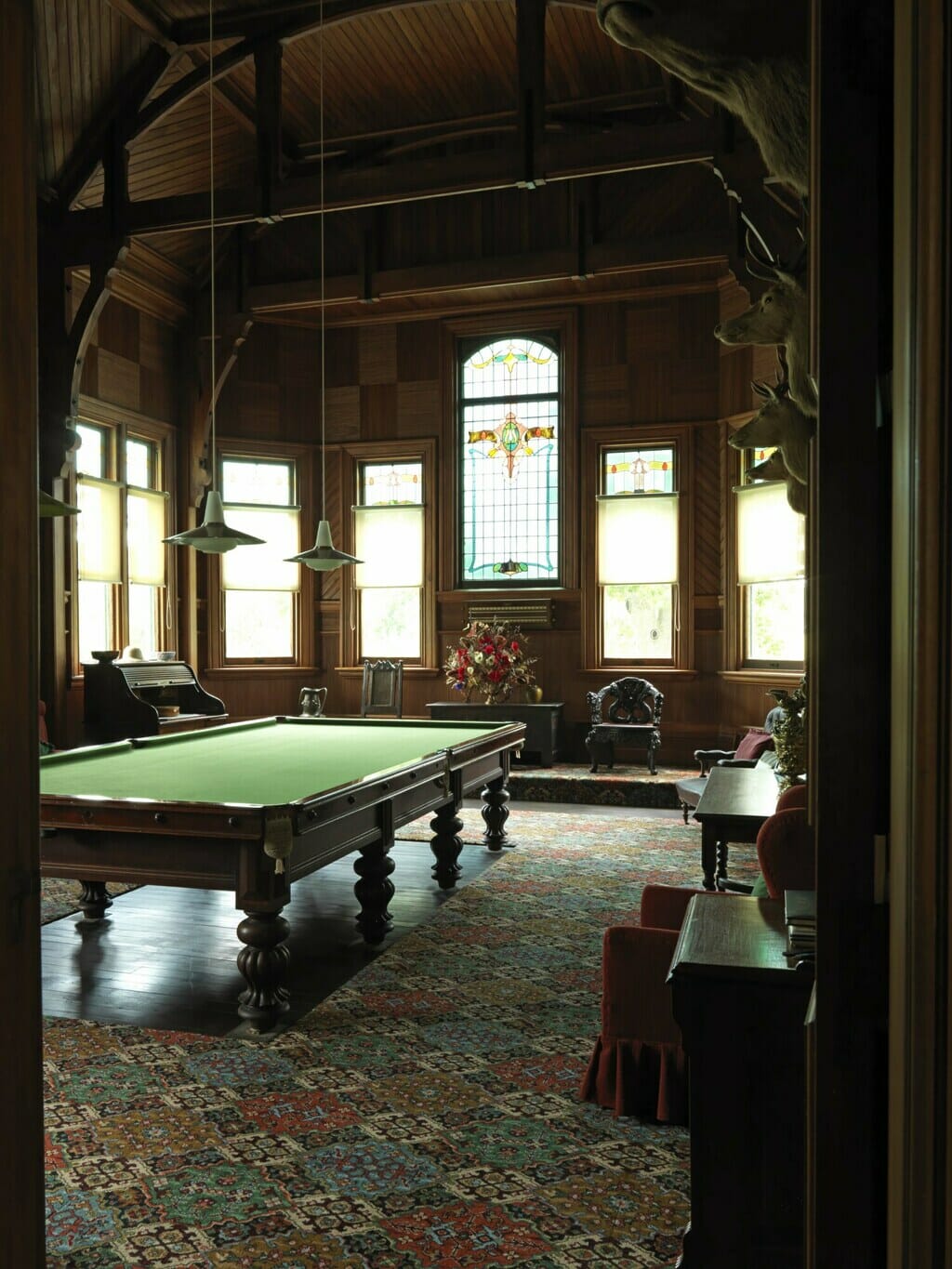

The chapel-like billiard room on the northeast corner of the house has rimu panelling carved by Ngāti Hauiti carvers, reminiscent of tukutuku patterns found in wharenui. Edith and John Hammond were fluent in te reo and were made honorary Ngāti Hauiti chiefs as a result of their close connections with the local iwi, according to Richard. Stained-glass windows in the billiard room exhibit the art nouveau influences reflected throughout the house’s interior detailing. An entrance door with stained-glass panels and floor tiles with a Greek key pattern in the main south-facing entrance continue the interior decorative flourishes.

A wide range of timbers were used in the house — mataī, tōtara, kauri and rimu for interior finishes, Oregon pine for the framing, redwood for window frames, and Australian tallowwood for flooring and blue gum for beams.

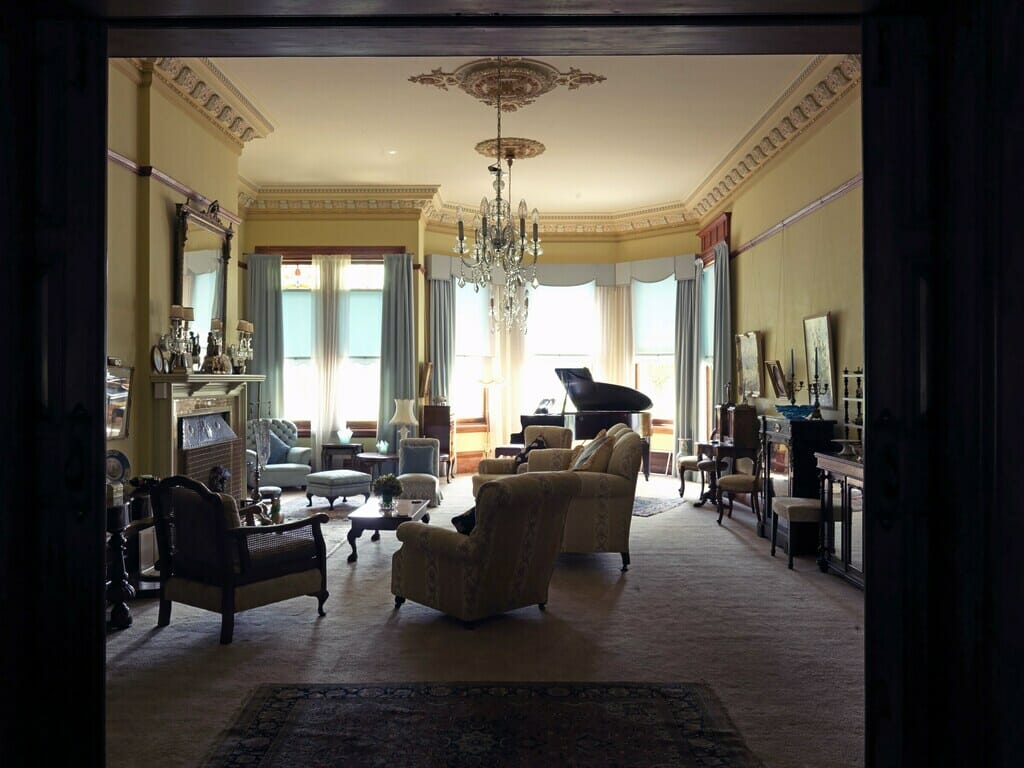

The dining room has a sprung kauri floor, and massive rimu cavity sliding doors that open to the adjoining formal drawing room, so that the two spaces can be converted into a ballroom. A grand piano in the drawing room dates from the time of Richard’s grandmother Beryl Hammond.

These days the formal rooms are seldom used except for extended family gatherings and guided house tours. Richard and Vicki, who moved into the homestead in 2017, occupy just six recently refurbished rooms on the ground floor at the rear of the house, which are now centrally heated. Richard’s mother lived in the house until she was 90, and it had been empty for four years when Richard and Vicki decided to move there from their neighbouring farmhouse.

The present-day station is 910 hectares, a fraction of the 11,000 acres (4500ha) in John and Edith Hammond’s day. Richard marvels to think of his great- grandparents breaking in the land, which was so densely covered in bush that farm access was gained by crossing the Rangitīkei River — sometimes up to 20 times a day. It was only when tractors started to be used in the 1930s that the farmland was finally cleared.

At the time the homestead was completed the railway line extended to Hunterville. Weekend visitors would travel by train from Wellington and the surrounding district to the station at Rātā. From here they would be collected in buggies and driven to the house, where they would arrive via a driveway that skirted a pond and crossed a bridge that is still a feature of the immaculately maintained 3-hectare gardens. Stables were located behind the house. When the age of the motorcar arrived, the driveway was moved to its current position closer to the house and encircling the stone fountain.

Horses still play a big part in the life of the station. Vicki is a keen rider and has been deputy master of the Rangitikei Hunt, which was started by Richard’s great-great-grandfather. An annual hunt is still held on Merchiston. Vicki travels to Marton to work during the week, and Richard is kept busy managing the station’s Angus beef breeding programme. The family has plans to open the homestead and grounds to more visiting tour groups and for special events. Merchiston is owned by an extended family trust, with Richard’s brother Lloyd and sister Helen and their families all part of its activities.

A full-time gardener and groundsman is employed, and a carefully planned maintenance programme has kept the homestead in pristine condition. But the upkeep of the house and garden is a constant drain on the station’s resources and maintenance is carefully staged to keep costs in check.

Despite the homestead’s proximity to State Highway 1, and its Category 1 Heritage New Zealand listing, it remains a little-known landmark of the Rangitīkei district. Entering its tree-lined driveway seems to instantly transport visitors back in time. Ironically, when Edith Hammond built her grand mansion it would have been considered the height of modernity. Towering beside the homestead today is a Lombardy poplar, thought to be one of the oldest in New Zealand. It grew from a stick Edith used as a riding crop when she and John Hammond rode across their property to select the site for their first home. Like the homestead, it is testament to Edith’s vision and the legacy left for future generations of the family.