The planet is warming up, and we need to change the way we grow to create resilient gardens that can cope with weather extremes.

Recently, a friend asked if I spend a lot of time worrying about climate change. I really had to stop and think about it. Absolutely, climate change is on my mind every day. Should I really buy that dress? Can that packaging be recycled? Would it be better to get that second-hand? But I find that contemplating climate change is a bit like thinking about space – its scale is so enormous that I feel overwhelmed and sometimes slightly fatalistic.

Internationally, there is evidence of climate change altering our gardens. A recent UK study showed that on average plants are flowering 26 days earlier than before 1987, and gardeners across Aotearoa say plants are working to a new schedule. A Whangarei gardener I interviewed last July reported that all her spring-flowering bulbs were blooming a month earlier, and on the West Coast, my parents-in-law harvested their tamarillos in June rather than October and their apple tree blossomed and set fruit twice within a year.

Without large-scale international change, it can be hard to see how composting our food scraps or replacing our lawns can help save the polar bears or prevent the sea from rising. But the act of gardening provides us with agency to have a positive impact in our own tiny corner of the world – and as more extreme weather becomes the norm we can prepare our gardens by making them more resilient.

Grow Trees – the original ecosystem regulators

All plants “sequester”, or take carbon out of the atmosphere during the process of photosynthesis to help them make glucose so they can grow. They store it in their leaves, branches, stems and roots. Their longevity and mass make trees best at this job, which is why there are massive tree-planting projects all over the world. Gardeners can play their part by planting a tree or 10. Even if you don’t have much space, you’ll still have room for something small. Many magnolia and Japanese maple varieties are suitable for small sections, or opt for a small kōwhai or a forest pansy.

Plant Natives

It’s a bit of a no-brainer that native species, which have evolved to our conditions, are best suited to our environment. This doesn’t mean they’re immune to climate change, but a 2020 study by the Bio-Protection Research Centre, hosted by Lincoln University, showed that they’re better at sequestering carbon and that when exotic plants decompose, they release 150 percent more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere compared with natives.

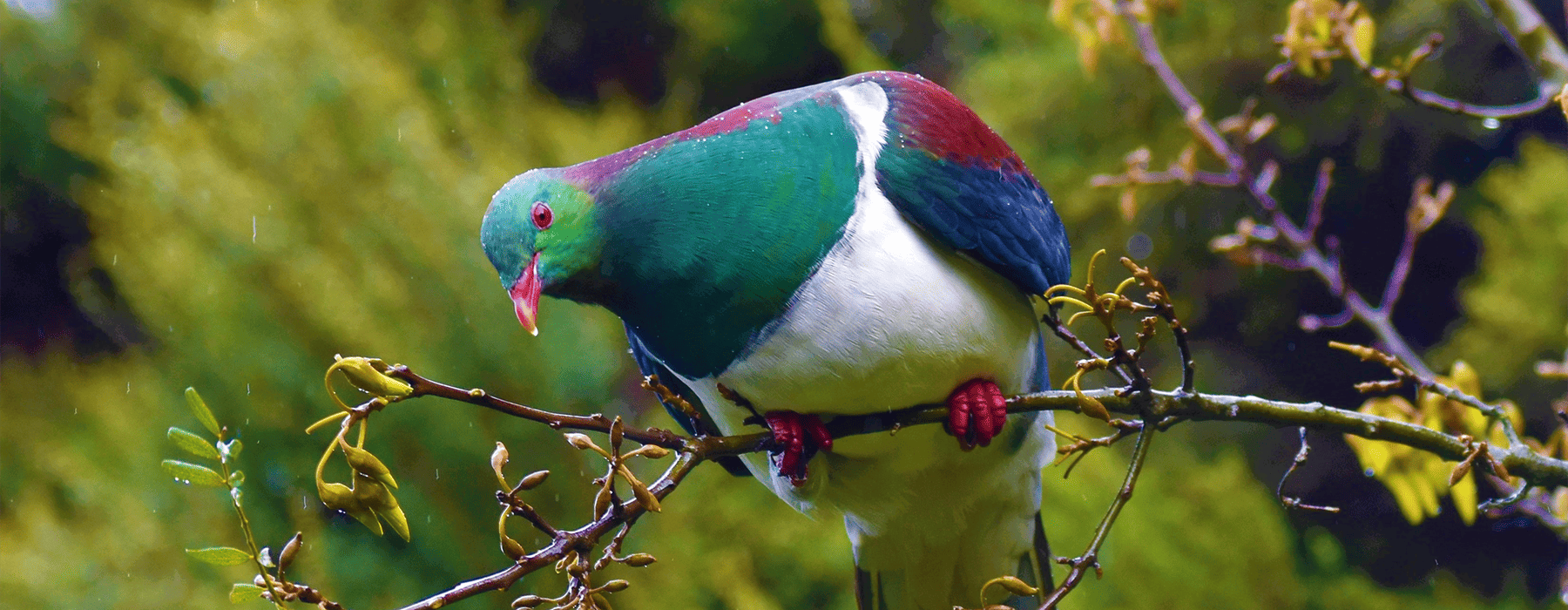

By planting natives, you’re also providing ideal food and habitat for our indigenous birds, insects and lizards. Forest & Bird has information on its website about native bird species and their preferred foods, but if you have the space, a pūriri will provide nectar, fruit and seeds almost year-round, and if you don’t have much room, kōwhai and flax provide tūī and bellbirds with nectar. Don’t overlook a pittosporum hedge either, which serves up fruit, seeds and nectar.

Right Plant, Right Place

Before you plant any new species, check that it’s suitable for your climate. This goes for native species too, as many of them are endemic to particular regions – for example, puka don’t like frost. Most councils have information on their websites about plants that are suitable for your area, but you can also see what grows well in your neighbourhood.

Auckland Botanic Gardens, which is part of the international Climate Change Alliance of Botanic Gardens, carries out trials to investigate which plants are suited to the local climate and maintains a database of these on its website.

“Planting things appropriate to the conditions rather than struggling to maintain unsuitable plantings is a big part of making things easy for ourselves and sustainable in the long run,” says Ella Rawcliffe, who is the Gardens’ botanical records and conservation specialist.

“We also keep an eye on pest plants and diseases, which are both likely to become more prevalent as conditions in Auckland become warmer and there are more extreme weather shifts.”

While you don’t need to go full succulent and pull out all your roses yet, it’s worth thinking about plants that can cope with extreme weather and drought. Good options include borage, hebes, echiums, figs, geraniums, French lavender, pelargoniums, cotton lavender, rosemary, bird of paradise and grapes.

Grow Your Own Food

Food waste statistics in New Zealand are pretty appalling. The Kantar New Zealand Food Waste Survey shows that we waste more than 100,000 tonnes of perfectly good food per year. Vegetables make up a third of the figure, with oranges, mandarins, apples, bananas, potatoes and lettuce appearing in the top 10 list of foods we waste the most. Though it’s still too cold to grow bananas in many parts of the country – for the time being – it’s easy to sow and grow greens such as lettuce, silverbeet and perpetual spinach (a silverbeet lookalike that is much less finicky than regular spinach). And if you have room, don’t forget to plant a fruit tree or two.

Love Your Soil

One of the keys to sequestering carbon is to treat your soil right. Healthy soils are like sponges and will soak up carbon from dead plant matter – you can even call yourself a carbon gardener!

The first rule is to never leave any soil uncovered. Just as you don’t see naked patches of soil in nature, ensure your soil is densely planted with a diverse range of plant species. Diversity is important because the roots of different plant species will penetrate the soil at different levels, resulting in maximum carbon drawdown. Think of this as living mulch. Borage, nasturtiums, phacelia and marigolds are all good living-mulch contenders. If vege gardens are left bare in winter, plant nitrogen-fixing cover crops such as legumes or blue lupins to avoid the soil sitting bare for a season.

Alternatively, lock moisture into the soil by adding a layer of pea straw, bark or compost around your plants. Don’t forget to mulch around plants in pots too, as they dry out quickly.

Instead of tilling soil, opt for “no dig” methods to avoid releasing carbon back into the atmosphere, damaging the soil structure and disturbing the microorganisms doing the hard work underground. Instead, build your garden beds up with compost, manure and other organic matter.

Make Compost

Home composting is a more environmentally friendly option than sending food scraps to landfill where they emit methane, a greenhouse gas that is significantly more potent than carbon dioxide. Compost is the ultimate soil conditioner, and homemade compost is the best you can get because you know exactly what goes in it. To make good compost, aim for a 50/50 mix of greens, which add nitrogen, and browns, which add carbon. Greens are plant matter, fruit and vegetable waste, coffee grounds, grass clippings (never add more than 5cm at a time as they’ll stink out your bin), weeds and animal manure. Browns are dried leaves, dead branches, twigs and cardboard.

Water Wisely

Last summer was the fifth driest on average in New Zealand and 55 locations had a record or near-record warm summer. This trend means that water restrictions will become more widespread across the country. Consider installing a rainwater tank that diverts rainwater from your downpipe. We have a DIY one that collects the water that runs off our garage roof and stores it in an upcycled food-grade barrel.

It’s important to water correctly. Limit watering to just two or three times a week during the hottest part of summer, and make sure the water penetrates about a spade’s depth down into the soil. This will encourage plants to send their roots down deep where it’s cool, making them more resilient during dry periods.

Gradually harden up plants such as fruit trees so that they can cope without any additional water. Plants in nurseries that have been cosseted with daily watering won’t survive if you plant them and leave them to fend for themselves. However, if you start off by watering them just once a week or so in summer, then gradually reduce the amount of water over time, they will adjust their growth rate to suit the new conditions.

Lose The Lawn

Think hard about whether you really need a lawn. In a 2022 study by Auckland University of Technology, researchers showed that once mowing, fertiliser and watering are taken into account, lawns actually emit carbon rather than capture it, and that if a third of grassed spaces were returned to treescapes in cities, up to 1600 million tonnes of carbon could be absorbed from the atmosphere. Consider replacing your fine sward with a diverse selection of plants, or plant more trees – an orchard would be lovely!

Feed Naturally

Synthetic fertilisers disrupt the relationship between plant roots and microorganisms, and they emit a lot of carbon into the atmosphere when they are manufactured. Instead, give your plants a boost by enriching soil with compost and manure, or make nutrient-rich tonics out of natural ingredients. To make seaweed tea, fill up a tub with seaweed, add water, put a lid on it and leave it to sit for three weeks. Dilute it with water to the colour of weak tea before spraying it on your plants. You can use this method with weeds as well, especially troublesome ones that you don’t want to relegate to the compost heap.

PHOTOGRAPHY: GETTY