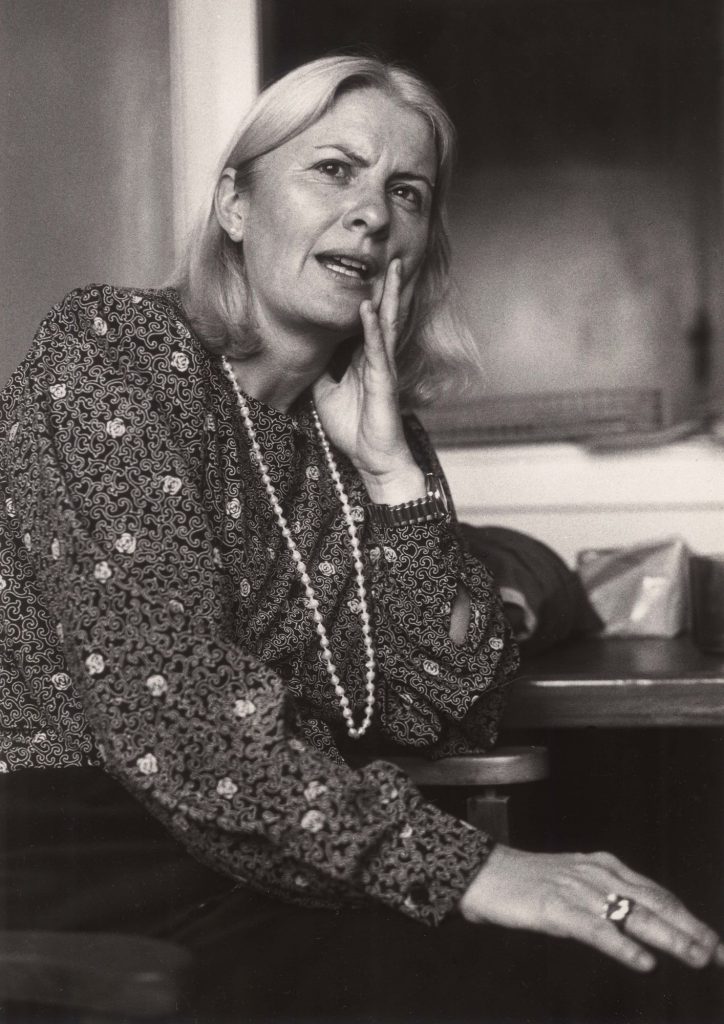

Feminist politician Margaret Wilson’s life has been a page-turner. She reflects on public service and the patriarchy in a new memoir, writes Sharon Stephenson.

There are two things you know for sure if you’re born a woman. First, that the world isn’t tilted in your favour. Second, that if you want to get anywhere, you generally have to work harder and faster than those with a Y chromosome.

Margaret Wilson – former Labour MP, Attorney-General and University of Waikato professor – received the hard work message early on.

“I’ve always been driven,” says Margaret from her Hamilton home. “And achieving equality is what drove me. It seemed to me that women were treated differently for no good reason, but I realised equality was absolutely fundamental if we were going to change anything.”

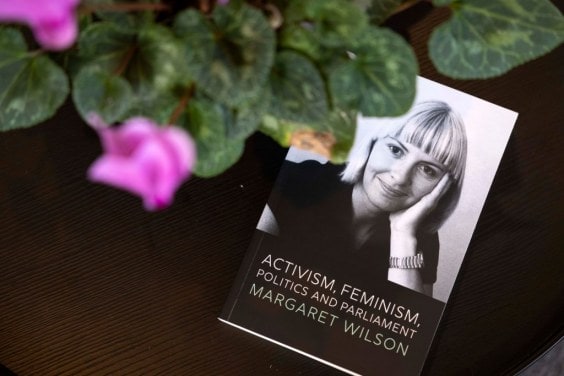

It’s an issue the 74-year-old writes about in her new book Activism, Feminism, Politics and Parliament, stitching together memories from her 50 years in public service as a unionist, lawyer, politician and lecturer.

There are chapters devoted to Margaret’s time as a law student, when she was only one of seven women in an intake of 200; the time she had to steer the governmental boat through tricky Treaty negotiations; even the time when, as Speaker of the House, she ordered her friend and then Prime Minister Helen Clark out of the debating chamber.

It’s a thrilling ride, one that Margaret says she spent almost four years writing. “I wanted to get it all down before I start forgetting things, but also while I still have the energy for it.”

Most weeks in politics are difficult, but the week of our interview has been especially tumultuous: Auckland remains in Level 4 lockdown, the rest of the county has dropped to Level 2 and Aotearoa is grappling with the aftermath of a terrorist attack. How does Margaret think the government is handling these issues?

“Government is all about balancing the needs of the individual with the community, which is never easy. This government has done extremely well to get through this, but it will become harder as people become weary and resistant to lockdowns.”

Margaret is especially pleased with the push for vaccination, not least because she’s the Deputy Commissioner of Waikato DHB and an enthusiastic cheerleader for immunisation.

“I’ve just opened a new vaccination centre in Tokoroa,” says the woman who shows no signs of slowing down. “I’ve always had lots of stamina, despite the cancer.”

She’s referring to the cancerous tumour she discovered in her left leg when she was 16. Within a week, Margaret’s leg had been amputated above the knee and a prosthesis fitted. It was a surgery that would cause her chronic, life-long pain.

“I didn’t want to take too many painkillers because I worried they would affect my judgement.”

It’s why she’s never been a planner, a to-do lister, or a buyer of five-year diaries.

“I worried that the cancer would return, so I’ve never really planned my life. I’ve just taken it as it came and made the most of it.”

It’s also why Margaret opted for a career in law. At the time of her surgery, she was studying to be a PE teacher. But that no longer felt possible, and Margaret cast around for a career that would support her financially.

“Choosing law was primarily about making me financially independent. Being dependent on others when you have a disability really does constrain your life. But I grew to love the law and was driven by the belief that everyone should know the rules and what their legal rights are.”

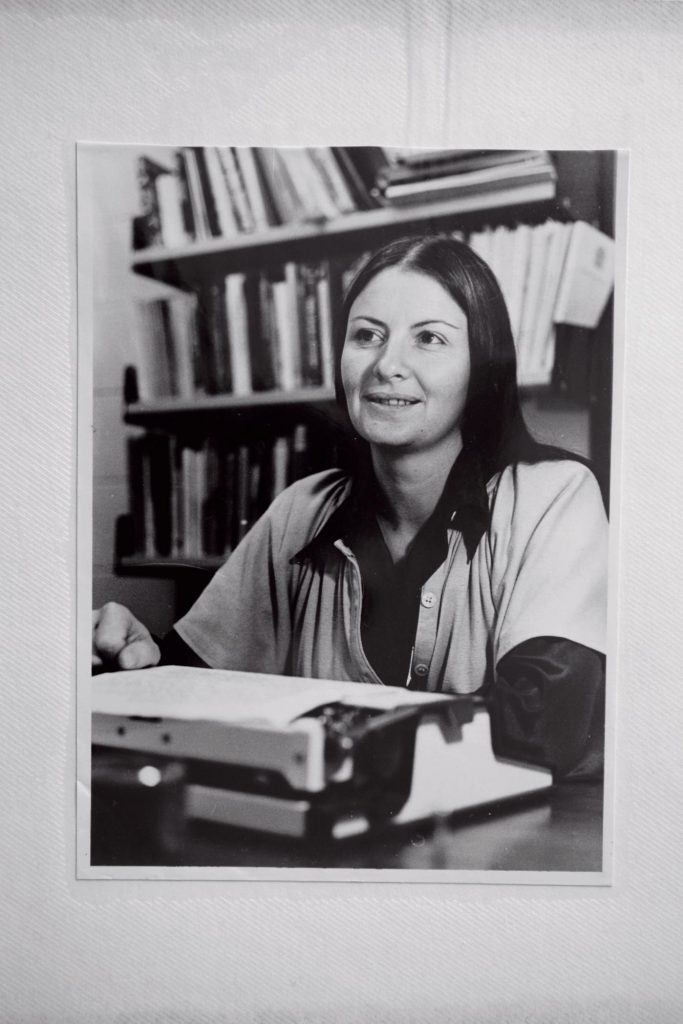

PHOTO SUPPLIED

I grew to love the law and was driven by the belief that everyone should know the rules and what their legal rights are.

Ironically, Margaret didn’t always have such a healthy respect for the rules: an early chapter in her book highlights how she was kicked out of kindergarten for stealing cocoa from the kitchen.

“Morrinsville winters were cold!” she declares in her defence.

Margaret was born in Gisborne, the eldest of four children. Her parents later ran a grocery store in Morrinsville and she attended the same high school that Prime Minsiter Jacinda Ardern later went to.

After graduating from the University of Auckland, Margaret got a job at a barrister’s office, and volunteer work for the Legal Workers’ Union kept her busy.

Her great-grandfather was a Liberal MP and her father was on the Morrinsville Borough Council, so politics weren’t totally foreign to her. She probably would have continued as a lawyer, campaigning for women’s and workplace rights, if it hadn’t been for Robert Muldoon becoming prime minister in 1975.

“Muldoon was so unfair and we all wondered, ‘How could this happen?’ It was such a reversal of the values that I had. I knew I had to get involved to fight for the life I wanted to live.”

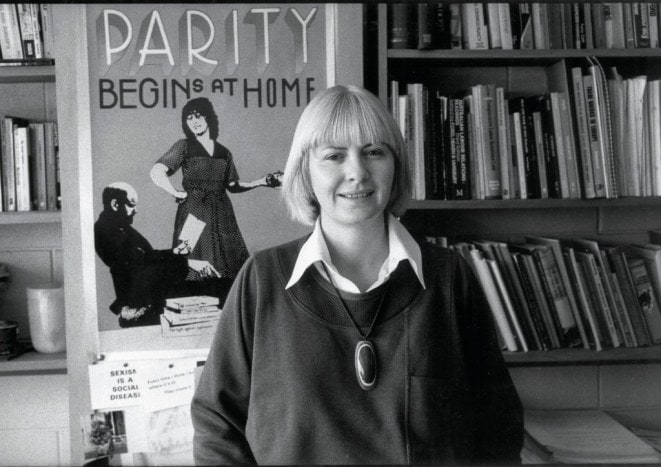

Margaret eventually became Labour Party President, working under David Lange and banging the drum for women’s rights and employment equality.

But when the party lost the 1990 general election, Margaret moved back to Waikato as the founding professor of the University of Waikato’s law school.

Then one day in 1999, the phone rang. It was Helen Clark, asking Margaret to come back. She did just that, entering as a list MP who was bumped straight into Cabinet – a rare move for a new MP.

It was a frantic but fulfilling nine years during which Margaret variously held the Labour and Treaty Negotiations portfolios, was Attorney-General and Speaker of the House.

Her wins were many, from establishing the Supreme Court and overseeing Treaty of Waitangi settlements to causes even closer to her heart – equal pay and parental leave legislation.

“We made a lot of progress in getting equal pay, human rights and equal opportunities on the agenda,” she says modestly.

Like everyone in the public eye, Margaret had her critics: from what she wore to rumours that she lost her leg in a motorbike accident. And then there was the unfair “she doesn’t smile enough” comments.

“That was usually because I was in pain with my leg.”

Margaret also copped flak for being single and not having children.

“It’s interesting how people thought I couldn’t comment on family issues because I didn’t have children. And I remember it being raised as an issue when Jenny Shipley and Helen Clark were leaders. But having kids wasn’t practical for me. I needed a good income to be able to raise them on my own, and it would have been difficult to do my job with children. Plus, being a single mother wasn’t easy back then and, to be honest, the biological urge wasn’t strong.”

Instead, Margaret relished the opportunity to be an aunt to her five nieces and nephews.

“The role of aunt is important and not enough people talk about that. Aunts provide an important place not just for young people to have secure conversations they might not be able to have with their parents, but also for money if needed. I love my role as an aunt.”

Margaret started writing her memoir in her former Hamilton house and ended it in her new town house, at the oak desk she inherited from her great-grandfather.

“Last year, my twin younger sisters decided we should all downsize our homes and prepare for the next stage of our lives. So we found these three town houses next to each other.”

Margaret shares her home with Madam, a rag-doll cat who “adopted” Margaret shortly after her previous cat was run over.

“Madam belonged to my former neighbours, but decided she liked my house better.”

Although losing her leg put an end to her many sporting pursuits, Margaret still loves watching sport – the day we chat, she’s keeping one eye on the TV, watching the cricket.

The rest of the time, she’s spending lockdown like most of us: cleaning out cupboards (“I’ve got rid of 40 years worth of papers”). What she’s not doing is cooking – “I can cook, but I don’t enjoy it.”Ask Margaret about her future plans and she admits retirement “could be on the cards at some stage”.

“I’m not a planner, as you know, so the fact I’ve made it this far is amazing! But I’d like more time to read the histories and biographies I enjoy, and to establish a garden.”

But that doesn’t mean she won’t keep the feminist fires burning.

“What keeps me awake at night is the way women’s rights are regressing. After 40 years of getting somewhere, the world is on the cusp of going backwards. Look at the US where they’re dialling back abortion laws, or the Taliban’s rise to power. We need to be so vigilant and aware that respect for equality and fairness is not universal. That worries me a lot.”