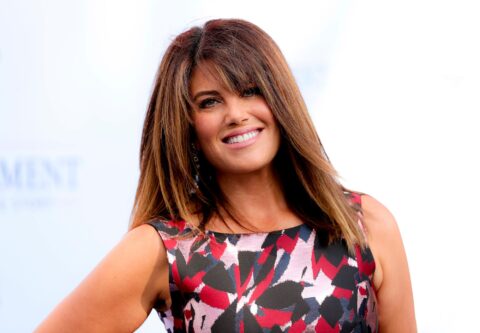

Author, radio host and mum of three, Stacey Morrison, talks to Thrive editor Niki Bezzant about the everyday family rituals that ground her, how losing her mother at a young age means she feels lucky to be growing older, and why she can never resist climbing maunga.

When it’s bedtime for Stacey Morrison’s three children, the whānau share a peaceful karakia, created by her husband Scotty. “It talks about how the sky is calm, the earth is still, and all of the world is still, and the sleep of everyone in this whānau will be content,” Stacey says.

Āio ana te rangi, āio

ana te whenua, āio

ana te ao katoa, āio

ana te moe a te whānau,

i roto i te māī,

te matihere, me te

māoriori e, kia au, kia

au, kia au te moe.

The sky is tranquil,

the earth is still,

everything is calm.

Our whānau sleeps peacefully, immersed in deep love and contentment,

sleep well.

– Scotty Morrison

It’s just one of the te ao Māori practices that Stacey (Te Arawa, Ngāi Tahu) relies on to nurture her family and look after her own wellbeing, while she deals with a workload that could easily make the rest of us feel like under-achievers.

Stacey and I catch up via Zoom, as you do these days, squeezed in between her other meetings, with accompanying background chatter from her children, aged nine to 15, who are doing schoolwork at home.

Later, she’ll head off to co-host her radio show with Mike Puru and Anika Moa on The Hits. She’s also found time in the past couple of years to co-author three books on te reo Māori, and recently released another, Kia Kaha, featuring stories of Māori who changed the world. She’s an active advocate for te reo, as is Scotty, who is also a TV presenter. Work for health-based charities, including Breast Cancer Foundation NZ, has a special place in her heart. Despite the various levels of Auckland’s lockdown, she’s continued to do a lot.

Stacey’s not sure she’s any different from anyone else though, and pushes back at those who say they can’t believe she fits so much in. “I say, ‘I think you do just as many things, it’s just that my things might be more visible.’”

And she loves flipping between different worlds and roles. “You have to be quite focused. I know that some people don’t like that way of working, but if that’s how you are, then it is quite energising.”

She’s learned, though, that even for her, being busy can take a toll, and she sometimes needs moments of quiet. “I’ve noticed that I drive in silence quite a lot now,” she says. “When you go out and put out a lot of energy, you do have to be realistic about how you’re going to feel afterwards.”

The spiritual side

Which is why those time-tested Māori practices woven through her family’s life are so important. Stacey is a fan of Te Whare Tapa Whā, a model for Māori health developed by Sir Mason Durie, which includes more than just physical and mental health.

“It talks about two other elements that perhaps get left out of other wellbeing models,” Stacey says. “And that is your taha whānau – how you’re interacting with your whānau and the social part of your life – and taha wairua, which is your spiritual side.”

It’s that spiritual side that enriches life and wellbeing for the Morrison whānau. “People will have different ways of practising it. For us, karakia – incantations – are a big part of us looking after our spiritual health.”

While we might think of karakia as prayers, they’re really more of a ritual; spiritual rather than religious. In fact, it’s not all that different from modern wellbeing practices like meditation and mindfulness.

“We’ll do it at least three or four times a day,” explains Stacey. “So we will have karakia for kai, when we’re going to eat. And that is really about mindfully being grateful for all of the resources that have come together for you to enjoy that food and how it sustains your body.”

Stacey reckons even if karakia isn’t your thing, “what you can participate in, and what the act is really about, is mindfully eating and mindfully thinking about what you’re nourishing your body with. That’s what I love, how efficiently karakia does that.”

She’ll also regularly say karakia at the start and end of hui (meetings). “And that has a different purpose: bringing energies together, recognising that people [might be] feeling heavy, so to try to shift that energy.

“I was part of a hui yesterday, and the others were a group who were able to get together, but I Zoomed into that. And still we can say karakia through a screen. We can still set intentions and recognise the energy in our room. Quite often, we talk about putting breath into your puku, and how calming that can feel.

“And in terms of our spirituality, sometimes it just requires you to look up, which is to look to the moon and look to the stars and have that moment of connection and not look down so much – like looking down at your phone… the environment will prompt you to think about things that you wouldn’t if you had your face in social media or in your emails.”

Looking up and looking out helps us connect more with the natural world around us, the birds and trees. “You can’t see those things unless you’re looking out. There’s spirituality in that.”

In mātauranga Māori, birds can be tohu – signs or messages. “And even plants and trees that you choose to have around you have meaning for us as well. One of them is at our door; we have karamū [coprosma]. We have that at our door because it kind of removes negativity. So it’s like an emblem for us… I guess like feng shui, right?” she smiles. “It’s to have a filter of positivity. Because Scotty and I have public roles and if you don’t dump stuff, of course it’s going to be heavy, because you’re just holding it all in yourself.”

Sometimes she thinks the health of the karamū reflects her own wellbeing. “I’ll have a look at it and go, oh, that’s looking a bit brown. That’s not getting much love, is it. That’s probably relevant,” she laughs. “You know, if you’re not thinking about what you’re looking after in your life, even if it’s a plant or another living thing that you’re taking care of, then it might be a reflection of how you’re feeling in general and what you’re spending time on.”

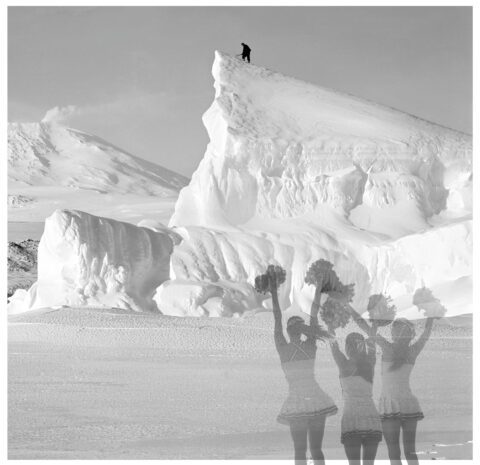

Maunga particularly resonate with Stacey. Wherever she travels, she can be found cajoling the family to hike to the top of a mountain. At home, she heads regularly to her local maunga (Ōwairaka), where Thrive photographed her. “It’s not even my maunga, it’s just a place that I relate to. We have a saying: E hoki ki ō maunga, kia purea koe e ngā hau a Tāwhirimatea – return to your mountains that you may be cleansed by the winds of Tāwhirimatea. I love that feeling of being on a maunga. It’s probably because I come from the south; from Ngāi Tahu.”

A loving legacy

There’s a strong thread of connection between past and present in the advocacy work Stacey does, especially for Breast Cancer Foundation NZ. She lost her mum to breast cancer almost 20 years ago, when she was just 45. Stacey was 27.

Before she died, Stacey’s mum, Sue, wanted to raise awareness of breast cancer. “She wanted to help even just one other whānau keep their mum around for longer, and we met at least one woman where that had been the case.

“I guess Mum gave me the example: even if something that’s happening to you is quite awful, you still have an opportunity to help somebody else. So I see that as legacy work for her.

“When you lose someone in a way that feels cruel – because it’s not long enough that you have with them – I think it’s helpful to have something that gives purpose to that loss, but also honours them.”

Her peers are now starting to lose parents, she says, and she can offer some comfort from her own experience of grief.

“I’ve noticed people my age or older thinking they don’t have a right to grieve as much as someone who loses a parent young,” she muses. “And also, underestimating how it will feel for them. No matter what your relationship is with your parents, this is a massive life event. It might be the first big life grief you’ve had.

“Grief feels like it’s pulling you down from within. And that’s a hard thing to experience, you know, in your middle age of life, when you’ve had a lot of life experience, but you haven’t had that experience.

“When you’ve been through that grief, it builds a different empathy with other people when they lose someone. So I just hope that people of my generation who lose their parents take that time to heal and don’t feel weak – even though it might seem like the natural order of life – and understand that it’s hard. It’s really hard.”

She feels the loss of her own mother all the time, still. “My sister and I were just talking about it today. She said, ‘Oh, Mum would be so proud of you’ for something I’d done. And for both of us it’s things like that we miss. We can’t talk to her about it. She never met her grandkids.

“I would have loved to ask Mum about childbirth. There were even things that I would have challenged her on. She didn’t have any cancer treatment for 10 months because she found out when she was pregnant with Georgia, and then she postponed treatment for 10 months while she breastfed her.

“And as much as I feel really grateful for being able to breastfeed my babies, if I was older, I would have said to her: ‘Breastfeeding is important, but you being around is even more important…’ but those are all conversations you’re not ready to have until you are older, you can’t anticipate it.”

Happy to be older

Stacey says losing her mum has made her think differently about ageing.

“I’ve outlived Mum by three years already, so I’m really mindful of that, and grateful for that, and grateful for my health as a result,” she reflects. “I’d be very ungrateful if I was mad about this privilege that I have, that my mum didn’t have. I’m very mindful that getting older is a privilege a lot of people don’t have.”

Stacey is interested in how her body changes and feels as she gets older.

“I think Mum always used to say, you know, it’s not as easy to get rid of weight after 30. And I was like – that’s not even a thing,” she laughs. “But then at around 45 I realised: okay, so it might be a thing.

“Of course, I have some vanity about ageing,” she says. “But I would like to look more within than from the outside about it.

“I think culturally we’re fortunate because as you age, as a Māori woman your roles can change, and the mana of women and the role and wisdom that older women carry is really valued.

“I think of some of the healers I know, who are quite often older Māori women, and there’s this security of feeling that they’ve lived a lot and they know more, and that is valued.

“I feel I want to be old. That’s one of my goals. To be old and be a really active grandparent. Both my husband and I have lost friends who are the same age or younger, so we’re really determined to be fit and healthy, and live a long life.”