Renowned for her remarkable pictures of World War II, Lee Miller is less well known as a fashion photographer. But as a key contributor to British Vogue, she did much to keep style alive despite rationing. A new exhibition and book have brought her extraordinary career to light.

*This is a voiceover created by AI and therefore some of the words or pronunciations may be incorrect. We hope you still enjoy this listening experience.

Fresh from swimming on the Côte d’Azur with her friend Picasso, 32-year-old photographer Lee Miller would have been dazzlingly tanned – pale blonde hair gleaming – when she turned up at British Vogue’s New Bond Street headquarters in September, 1939, on the hunt for a job.

On hearing that Hitler had invaded Poland, Lee and her lover, the artist Roland Penrose, had hightailed the 1300km trip from Antibes to Brittany’s Emerald Coast in a car, to board a boat back to Britain.

Both were ardent surrealists (he organised Britain’s first surrealist exhibition in 1936; she had lived and worked with the artist Man Ray in Paris during the late 1920s). They’d even met at a surrealist ball. It was like being “struck by lightning”, Roland said. A note she wrote to him afterwards was filled with one word: “darling”, over and over again.

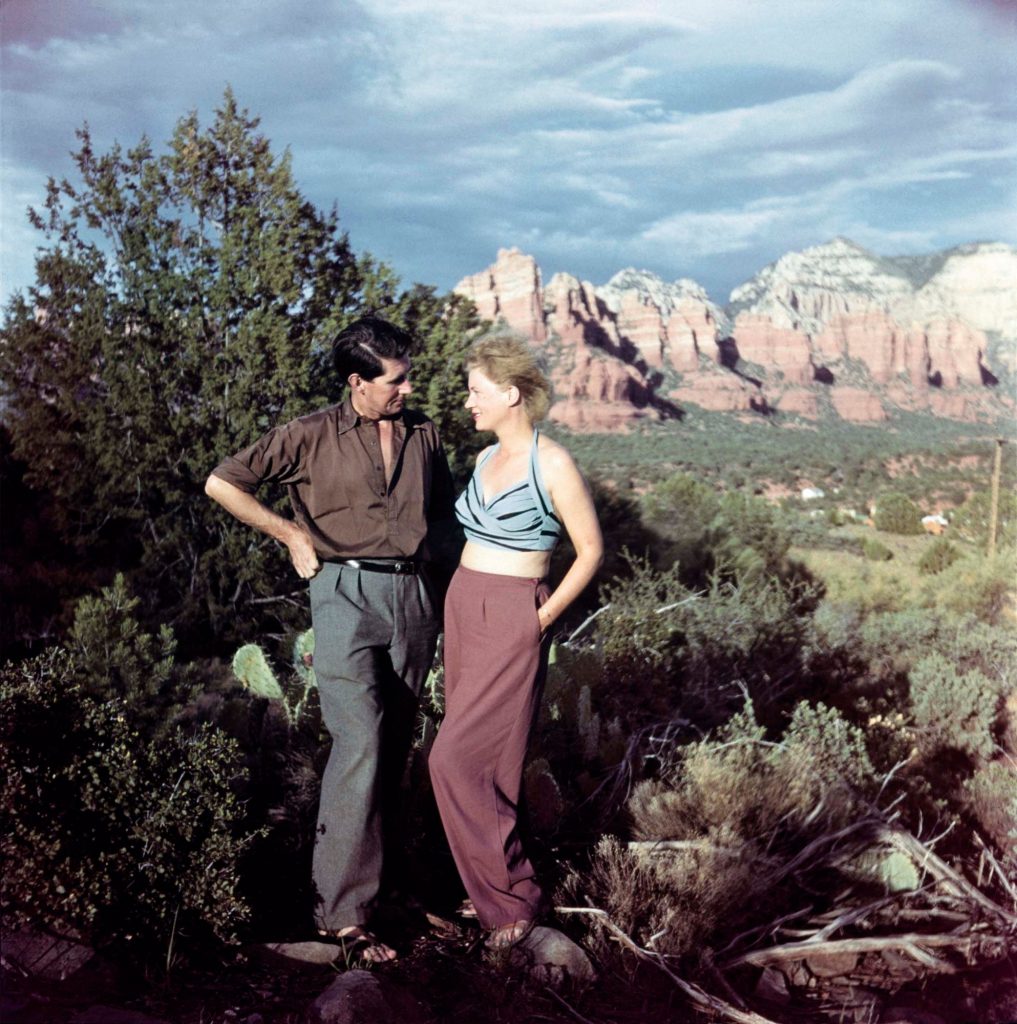

PHOTO FROM THE LEE MILLER ARCHIVES

When they got back to Hampstead after that boat crossing, Lee found a fierce letter from the US embassy insisting she return to her native New York for her own safety. Not that she heeded it, preferring to tear it up, pour a stiff drink and plot her next move: Vogue. One wonders if she asked Roland his opinion about any of it, but I doubt it.

Vogue, though, turned her down. They were doing just fine with Cecil Beaton, they said. Only they hadn’t reckoned with Lee’s grit. She began turning up at the magazine’s photo studio day after day, all bounce and bonhomie, making friends as only she could, and making herself so indispensable that, in January 1940, she was hired as a fashion photographer.

Lee’s star rose quickly. As revealed by a UK exhibition at Farleys House & Gallery – her and Roland’s former Sussex home and now a “house museum” – and the accompanying book Lee Miller: Fashion in Wartime Britain, she would become one of British Vogue’s most treasured and prolific wartime contributors.

Between 1940 and 1944, when she left for the front, Lee produced over 400 pages of fashion images. That’s before we even consider the photographs she took for Vogue’s pattern and knitting supplements.

“She has borne the whole weight of our studio production through the most difficult period in Brogue’s [British Vogue’s] history,” the magazine’s then-editor, Audrey Withers, wrote to her colleagues in America.

Lee’s credentials for the role were impeccable. Following her time with Man Ray, she had run a chic photography studio in 1930s New York (Saks Fifth Avenue and the actor Gertrude Lawrence were clients). Vanity Fair had named her “one of the most distinguished living photographers”.

Besides, in her youth, Lee had been an American Vogue cover girl, modelling for socially prominent photographers such as Edward Steichen and Arnold Genthe. None other than Vogue’s owner, Condé Nast, had discovered her, when she had been crossing a Manhattan street.

At 19, with daring garçonne-style short hair, she was blindingly beautiful. Even catty Beaton put his usual hauteur aside, comparing her to “a sun-kissed goat boy from the Appian Way”.

Given Lee’s international renown today, and the many times her work has been exhibited since her son Antony discovered it all entombed in their attic after she died in 1977, it is surprising to learn that nearly all the photographs in the new exhibition have not been seen since they were first in Vogue – if ever, in some cases.

PHOTO FROM THE LEE MILLER ARCHIVES

“We knew they were here,” says Lee’s granddaughter and director of Farleys, Ami Bouhassane. “All of her work was analogue, archived a long time ago, but we’re a small team and digitising has only been something we’ve been able to do as we go, and no one had asked for it. None of us knew how much of the wartime fashion material there really was, or how beautiful it is. A lot of the negatives were still in their original envelopes.”

None of us knew how much of the wartime fashion material there really was, or how beautiful it is.

PHOTO FROM THE LEE MILLER ARCHIVES

To everything she did, Lee brought glamour and flair. “She carried out these fashion assignments with great seriousness,” says Vogue contributing editor Robin Muir. “She brought to them the whole weight of her time in 1920s Paris and 1930s New York.”

The photographs have three qualities. First, their hard-edged brilliance; the world Lee creates is marvellously true and sharp, like cut glass. Second, their vigour – they sort of hum, with what I think of as a vestige of her own considerable energy. Third, their surrealist additions, such as egg boxes and curtain tassels, and even the recently invented Slinky toy.

“She got her dad to send one over from America,” says Ami. “Lee was fascinated by gadgets and new inventions. Our house is full of them.”

PHOTO FROM THE LEE MILLER ARCHIVES

The thing is, “utility” clothing, introduced by the government in 1942 under rationing, desperately needed Lee’s outlandish flourishes. The fringing and furbelows that made interwar fashion so gorgeous were long gone. There was nothing fancy (or sexy) about plain-cut tweed suits and woollen stockings.

No one had the money to buy fancy clothes or cosmetics anyway. In March 1942, photos by Lee accompanied an article that asked, “How is chic to be maintained on an income much reduced?”

“We don’t so much live as manage,” grumbled journalist Lesley Blanch. “It’s one long battle against lapsing into dullness and discomfort.”

Vogue had vowed in 1939 to remain “a tonic to the eye and to the spirit” during wartime, but one wonders how on-board Lee’s editors really were with her photographing models accompanied by inflatable fish and the like. Sadly, no memos detailing those conversations survive.

Ami thinks this is because Lee was mostly commissioned verbally. Certainly, her pocket diaries, with their scribbled appointments at Aperitif and other restaurants near Vogue’s offices, back this up.

“She drank five gins at lunch,” noted the magazine’s then managing director, Harry Yoxall, after one such “meeting”.

Of course, there is a question hovering over all of this like a barrage balloon. Because why bother with hairstyles and skirts and the like when the country is at war, the sound of planes ever in the sky?

Partly, it was about morale. “To work for victory is not to say goodbye to charm,” declared a wartime advert from cosmetics company Yardley. “For good looks and good morale are the closest of allies.”

Vogue’s American editor-in-chief, Edna Woolman Chase, was in this camp. In a 1939 memo to Harry, she reminded him that Vogue’s popularity during World War I had been down to it retaining “standards of beauty and of taste, which, in a devastated world, was a pleasing relief”.

Economics had a role, too, explained beautifully by a Picture Post feature in October 1940 that showed Lee hard at work in the studio, photographing model Jacqueline Craven in a Norman Hartnell gown.

In the accompanying text, Anne Scott-James (Vogue’s beauty editor) wrote: “Is it necessary to take all this trouble when the country is fighting for its life?” She answered: “Because standards are more important than ever… [Fashion] stimulates our exports… Fashion pays for ‘planes and supplies.’”

Which leads us to the third answer – influence. Women’s magazines reached an astonishing 93% of women at the time, giving them “a special place in government thinking”, explains Julie Summers, whose biography of Audrey Withers was published last year. “Ministers needed to have access to every aspect of women’s lives; to influence their thinking.”

During the Blitz, for instance, the Ministry of Food asked Audrey to encourage readers to prepare for winter by pickling and preserving fruit and vegetables, while the Ministry of Supply requested Vogue urge women to volunteer for war work. Other magazines, such as Woman and Home, also reported on practical war-related matters, though none reported on it directly in the way Vogue did.

As for the other side of the coin – those making the clothes that Lee was photographing – unlike in WWI, nearly all of the major fashion houses decided to stay open, though they had to rethink their way of working. Norman Hartnell, for instance, began sending sketches out to clients, and only cut precious fabric on request. Others trialled travelling shows.

But if Vogue kept calm and carried on, it was not easy. Staff at New Bond Street swept up broken glass and brick debris. Fashion models were scarce and sittings interrupted by air raids. If the alarm sounded, everyone had to trudge down six flights of stairs to the cellar, which had been kitted out with desks, a shovel and a stirrup pump.

PHOTO FROM THE LEE MILLER ARCHIVES

They rose to the challenge, though. Edna Woolman Chase observed in 1942 that her British staff had attained “a mystic quality. They seem truly to have found their souls.”

Lee wrote to her parents that it had become “a matter of pride that work went on, the studio never missed a day, bombed once and fired twice, working with the neighbouring buildings still smouldering, the horrid smell of wet charred wood, the stink of cordite, the fire hoses still up the staircases”.

Like many women, Lee and Audrey found a special sense of purpose in wartime. The more difficult things became around them, the better they coped.

“The two of them wanted more than anything else to make an impact,” explains Julie. “It made for a rock-solid working relationship that turned into a great affection for and trust of one another. Audrey understood Lee better than most – her vulnerability as well as her ambition.”

Eventually, though, Lee’s eyes began drifting to Europe, as she wondered whether she could be doing something more worthwhile. While photographing short hair was essential for the war effort (long hair and factory machinery made for hideous bedfellows), it was also deathly boring.

“It may be good for the country’s morale,” Lee wrote to her parents, “but it’s hell on mine.”

She applied for and received accreditation as a US war correspondent. Audrey, who “realised that Lee was about to produce a body of work the likes of which she would never see again”, according to Julie, did not try to stop her, though she also made sure she had first dibs on anything Lee produced.

“In a time of war,” Audrey would recall, when she was 87, “[Vogue] needed to report war, and Lee Miller might have been created for the purpose of doing just that for us.”

PHOTO FROM THE LEE MILLER ARCHIVES

Vogue needed to report war, and Lee Miller might have been created for the purpose of doing just that for us.

Lee’s first report in uniform came in 1944, from an evacuation hospital near Omaha Beach, in the wake of the D-Day landings. Soon after, she was the only woman correspondent at the siege of St Malo.

“I thumbed a ride,” she would write, “I had bought my bed, I begged my board, and I was given a grandstand view of fortress warfare reminiscent of Crusader times.”

PHOTO FROM THE LEE MILLER ARCHIVES

When she bumped into a friend there, Life photographer David Scherman, he was startled at the change in her.

“Steichen’s former fashion model had been a fastidious, obsessive clothes- horse,” he later recalled. “Now, in the excitement – and joy – of battle, all this nonsense went out the window… She looked like an unmade, unwashed bed.” Audrey gave six pages to the Saint-Malo report that Lee filed.

“Good girl, great adventure, wonderful story,” she replied, though she would become increasingly concerned about her protégée. Indeed, Lee’s onward journey into the war – pictures of dead soldiers, of Dachau concentration camp, and, in what is probably her most famous photograph, of herself unclothed in Hitler’s bath – came within a hair’s breadth of destroying her.

By the time she and Roland moved into Farleys in 1949, Lee was exhausted, depressed and an alcoholic. The house, which would later become known for its convivial gatherings of bohemians and dissidents, had to cradle her back to health.

It was the typed pages of Lee’s Saint-Malo report, now yellow with age, that Antony discovered in the attic in 1977. Until that moment, he wrote in his 1985 book The Lives of Lee Miller, “she had been so self-deprecating about her life and so dissolute in her later years” that this material he had unearthed – including some 60,000 photographs in all – uncovered a woman he had never known.

Audrey and Lee kept in touch until the end. On one of her visits to Farleys, Audrey brought with her as a gift two tumbler pigeons, so called for the impossibly graceful, daring aerobatics they perform when in flight.

Could there be a better analogy for Lee Miller? At any rate, their descendants leap and somersault over Farleys still.

Text: © Lucy Davies/The Telegraph. Photos: © Lee Miller Archives, England 2021. All rights reserved, leemiller.co.uk.