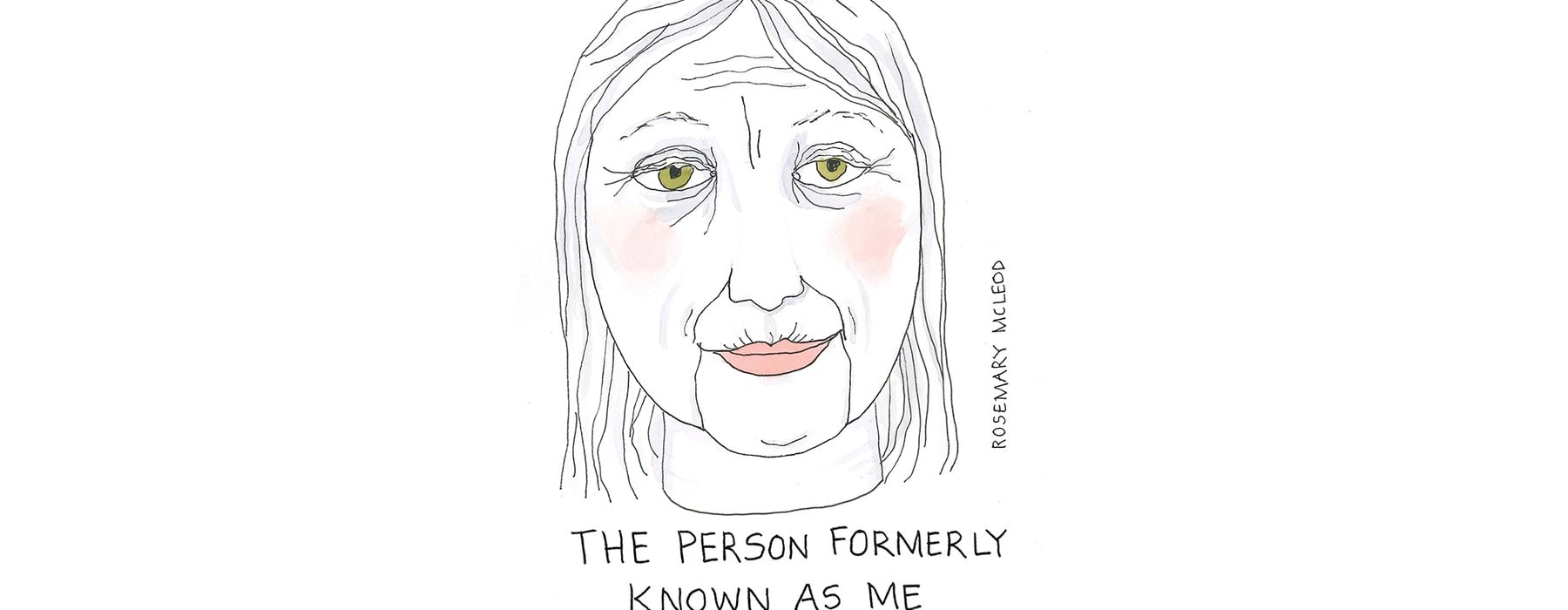

In a moment of reflection, Rosemary looks back at what she imagined her future-self to be and confronts the inescapable reality of ageing.

The woman who used to be me was going to be – and look – the same age for decades and have boundless energy. Her hair wouldn’t change colour or get thinner as the years rolled by. Hairy legs would be shaved promptly, even in winter, and hairs on her chin would be stalked ruthlessly and plucked. Other hair would be her own business.

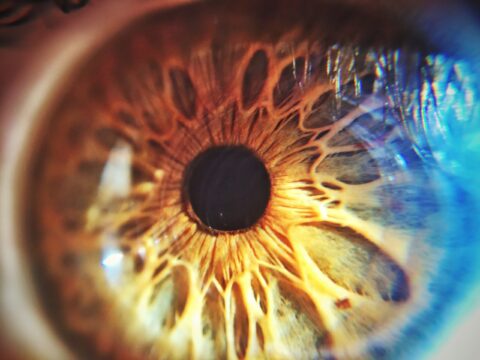

Her face would please her by not changing. She would not watch the organs formerly known as her eyes become small, overhung with curtains of pleated skin. Her lipstick would never bleed into her pleated lips – there’s an Issey Miyake theme here – or onto her teeth.

No ventriloquist’s puppet lines would form at the edge of her mouth, dragging down to her chin. When it came to Issey Miyake, she would recognise in time that his Pleats Please things were mainly worn by older women. And ditch hers. Denial is comforting.

She would not get deaf or need glasses, even though there were suddenly hearing clinics everywhere begging for her money. Unlike her father, as he aged, she would not hold books at arm’s length and pretend to read them or make gentle grunting noises as if she truly heard what someone just said. She would invent what they just said. It’s more interesting.

The veins on the backs of her hands would not become prominent and knobbly like her grandmother’s – like everybody’s grandmothers’. She’d have thought it unlikely that she’d have children, but she would have kids, and they’d grow up to be astronauts. Never in a million years would she need orthopaedic surgery.

Confident of her parenting skills because she’d read books, the woman would possibly lose any confidence at all, as is the inevitable way with parenting. Her children would laugh at her when she was angry, which was not in the books. This seems strangely familiar.

Her teeth would not get stained with tea and coffee and red wine. They’d gleam like an American TV anchor’s dazzling piano keys. They’d never need bridge work or implants, and she’d lose none ever. The torture at the school murder house would have been worth it. Her smile would not reveal shades of creamy grey fake teeth that never quite matched.

The woman who used to be me would now be older than both her parents ever got to be. She might think, occasionally, that she might not exist in the world forever.

That woman would laugh nervously at retirement home advertising trying to convince her that, if she bought in to a paradise-for-the-elderly, she’d be knocking back cocktails while elderly men serenaded her on the guitar. Or possibly the mandolin.

She wouldn’t drink cocktails anyway, especially if someone played the mandolin. The woman who used to be me fights against the urge to wear florals, and her legs are always covered for fear of frightening children. She will not wear the white, low-cut tops that rich, high-maintenance women with leather skin do. Too many pleats. Nor will she wear pastel colours or track pants. That’s a promise.

She’ll not wear clothes that she’d worn in a previous incarnation, like ribbed sweaters, batwing sleeves and above-the-knee skirts. As if her legs were ever her best feature. As if she has any idea what her best feature was. The woman who used to be me would be comfortable with technology, and never curse a keyboard or a digital alarm clock, as I do constantly.

She’d struggle with involuntary weeping, like when a three-year-old child lost overnight in the cold is found safe and well, or the SPCA advertises a glut of kittens, or – here she’d weep buckets – when the Duke of Edinburgh left instructions for his horse to be fed sugar lumps on the day of his funeral.

She would be embarrassing. It can’t be helped.