Sophia Loren started acting at 16, became a global icon in her twenties, was adored by Peter Sellers and Richard Burton – and, at 86, is still mesmerising on screen. But, she tells Stefanie Marsh, it all began with a childhood overshadowed by poverty, hunger and war.

Sophia Loren inhibits such a high-spec level of superstardom that she doesn’t even know The Rolling Stones wrote a song about her.

“Who?” she says, a disembodied, heavily accented voice calling from her home in Geneva.

“The Rolling Stones,” I repeat. There follows a puzzled silence.

The band’s ode to Sophia is on the bonus disc of 2010’s remastered Exile on Main St, a double album originally recorded in the early ’70s, around the time when – by implicit and infatuated international consensus – Sophia had artfully dodged the threat of being given ever-diminishing roles in the mould of “exotic hottie” by Hollywood, earning the rightful title, Screen Goddess.

But the song isn’t ringing any bells today. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards may be household names worldwide, but maybe not in the Loren household. “I know who The Rolling Stones are,” she says. “I’m not stupid! But I didn’t know about this song. Really? What is the title?”

Somewhere within range of her telephone speaker is the younger of her two sons, Edoardo Ponti, 48. He’s flown over from LA for 10 days to polish up his mother’s rusty English and shed light on the startlingly brilliant performance she gives in his new Netflix film, La vita davanti a sé (The Life Ahead).

They are close. Sophia was unusual among her peers for not developing any masochistic tendencies – no substance abuse, no car-crash love affairs. She married only once, and for life. Her husband was the Italian director Carlo Ponti, 22 years her senior, who, having spotted her in Rome when she was just 16, understood that here was a person with whom he’d like to spend his life, personally and professionally. They had two children: conductor Carlo Jr, 52, and film-maker Edoardo.

“The exceptional thing about growing up was how simple my parents always tried to keep it,” says Edoardo. “They were not people who invited Hollywood into their home, hobnobbing with actors. Acting was their day job. What they brought home was their passion for storytelling, their passion for the craft… It gives you that groundedness, knowing who you are, and it stops you from living co-dependently with this glamour thing. The spotlight is addictive. If you believe in it, you start acting stupidly to keep attracting it, and that was a trap my parents had the wisdom and intelligence never to fall into – because the spotlight becomes a black hole.”

The Stones song is called “Pass the Wine (Sophia Loren)”. “Passa el vino, Sophia Loren!” Edoardo translates for his mother with some excitement. She sounds amused, happy and satisfied by this title.

Thematically, it makes sense. Sophia was always the living embodiment of the non-Italian’s fantasy of Italy, the land of good food and wine: warm, witty, empathetic, stylish, good-looking, charismatic, abundant, assertive.

Hunger, she’s always said, was a major theme of her childhood. No film star in the world has been more photographed with food: eating whelks beside the Thames on the set of The Millionairess; pounding pizza dough in Recipes & Memories, her bestselling 1998 cookbook. The connection many men made between all these factors was well articulated by her friend Sir Noël Coward, who said, “She should have been sculpted in chocolate truffles, so the world could devour her.”

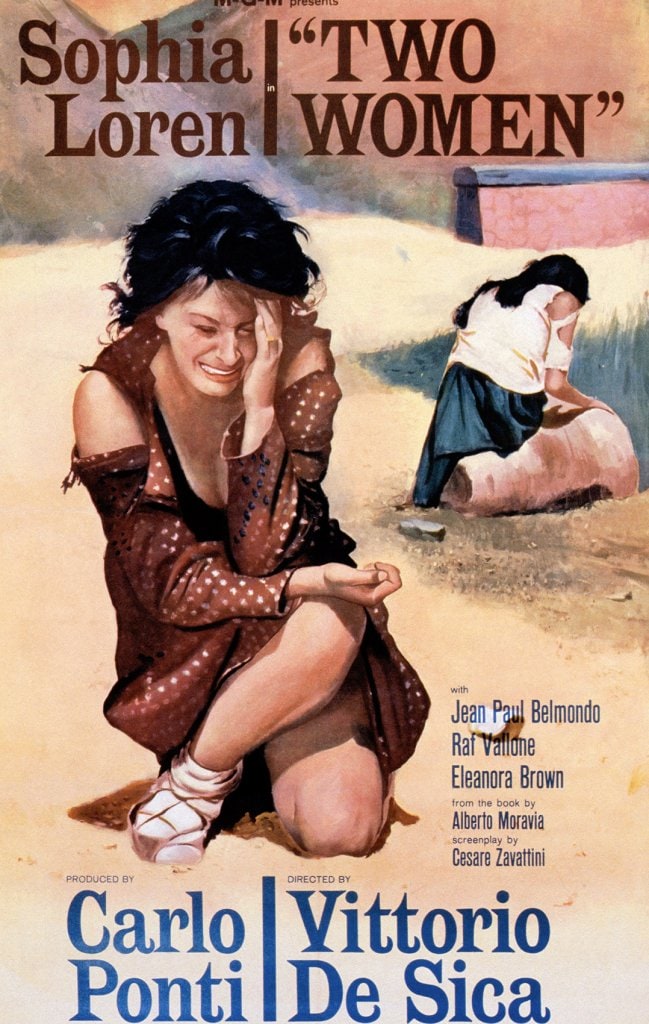

Two things are indisputable – that Sophia is a fine actor (the first to win an Oscar for a foreign-language film, 1960’s Two Women), and that men have always dropped like narcotised flies in her presence.

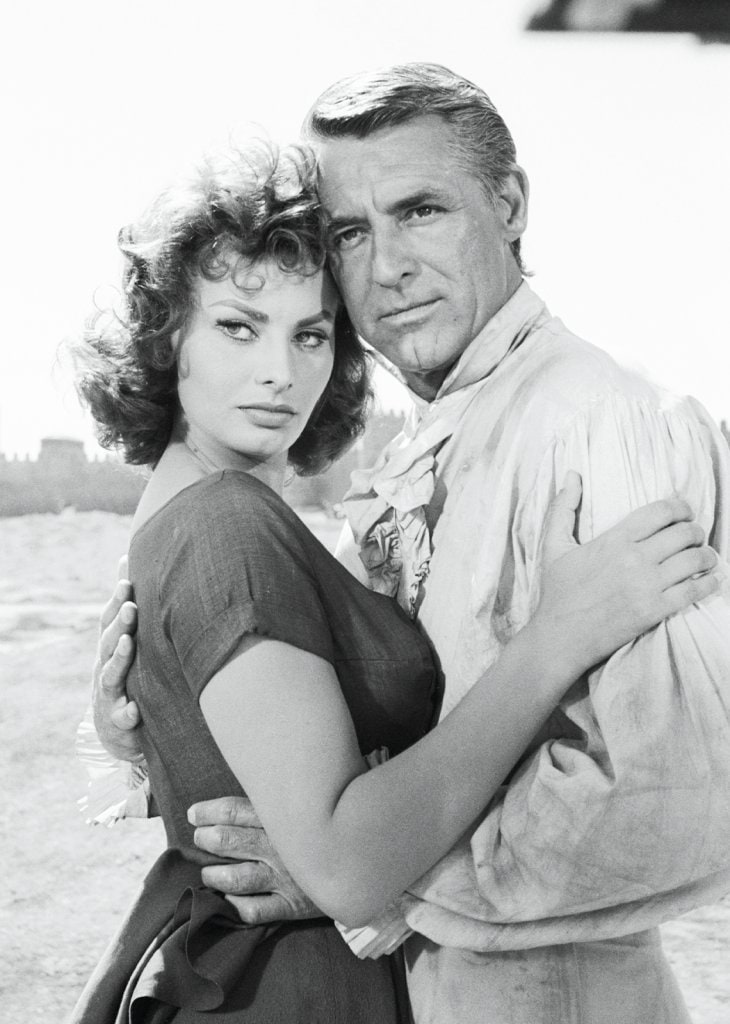

She turned down a marriage proposal from her leading man in Houseboat, Cary Grant, but at least he was granted the pleasure of a short relationship and a lasting friendship.

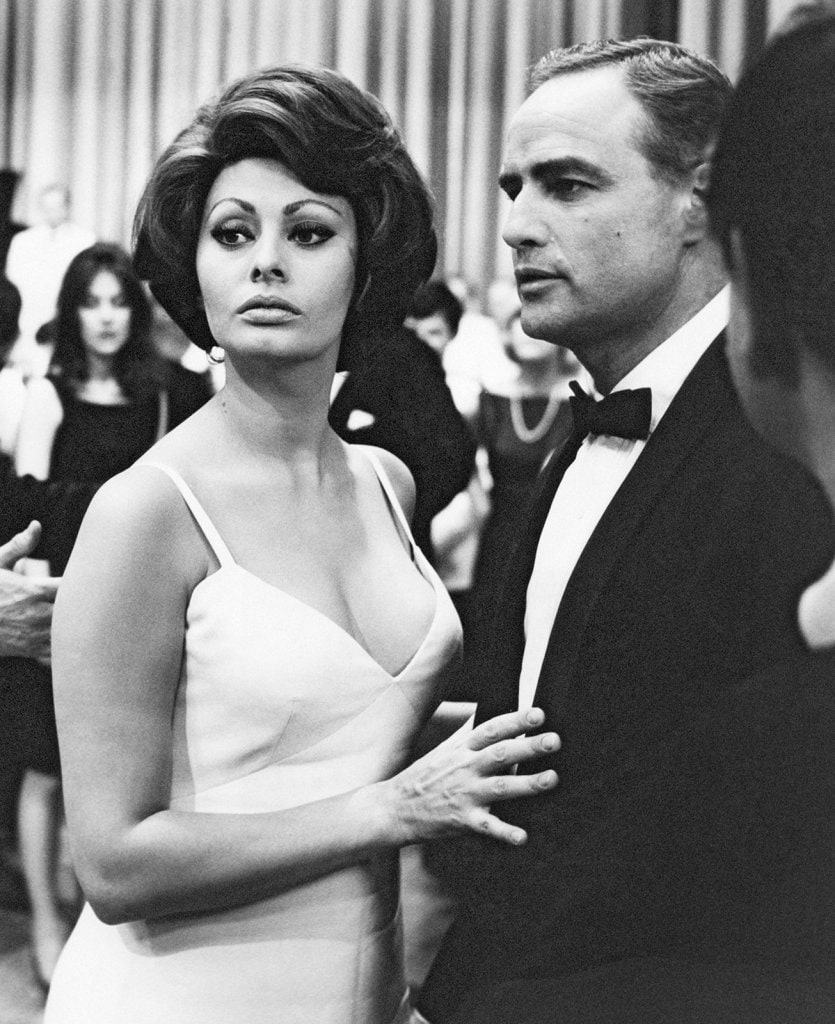

She rebuffed Marlon Brando.

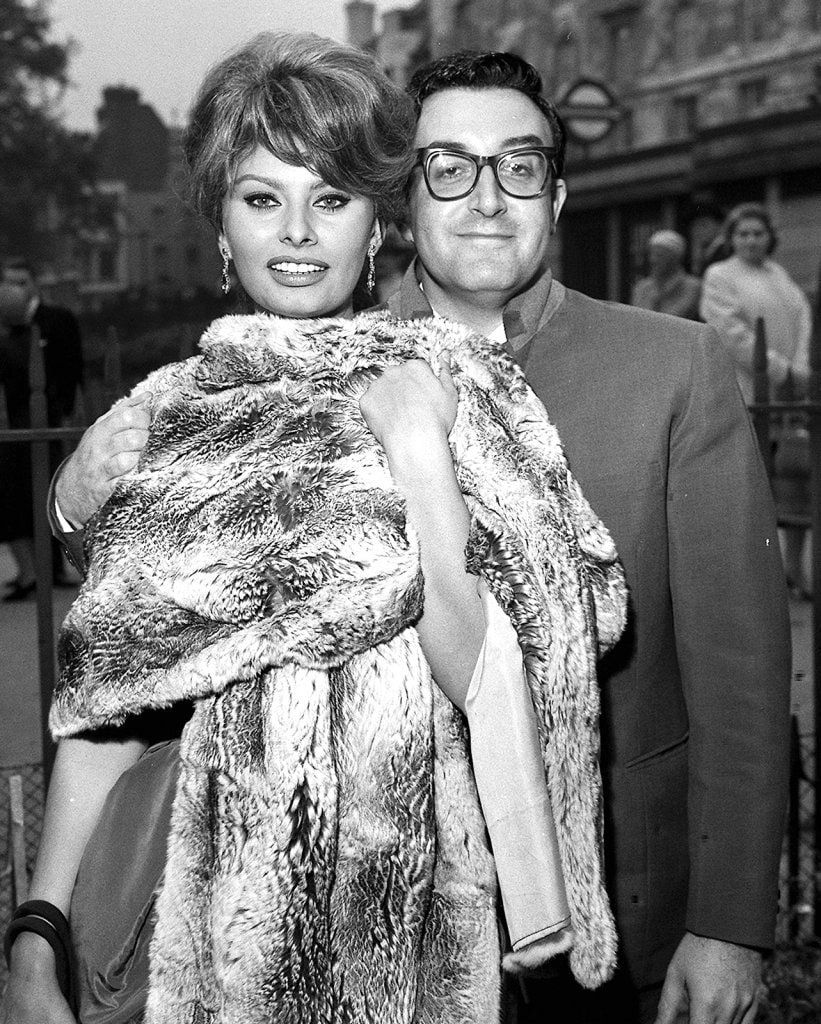

Poor Peter Sellers became so obsessed with her during the filming of The Millionairess that he left his wife and two children. (When his five-year-old daughter asked if he still loved them, he replied, “Of course I do, darling, just not as much as Sophia Loren.”)

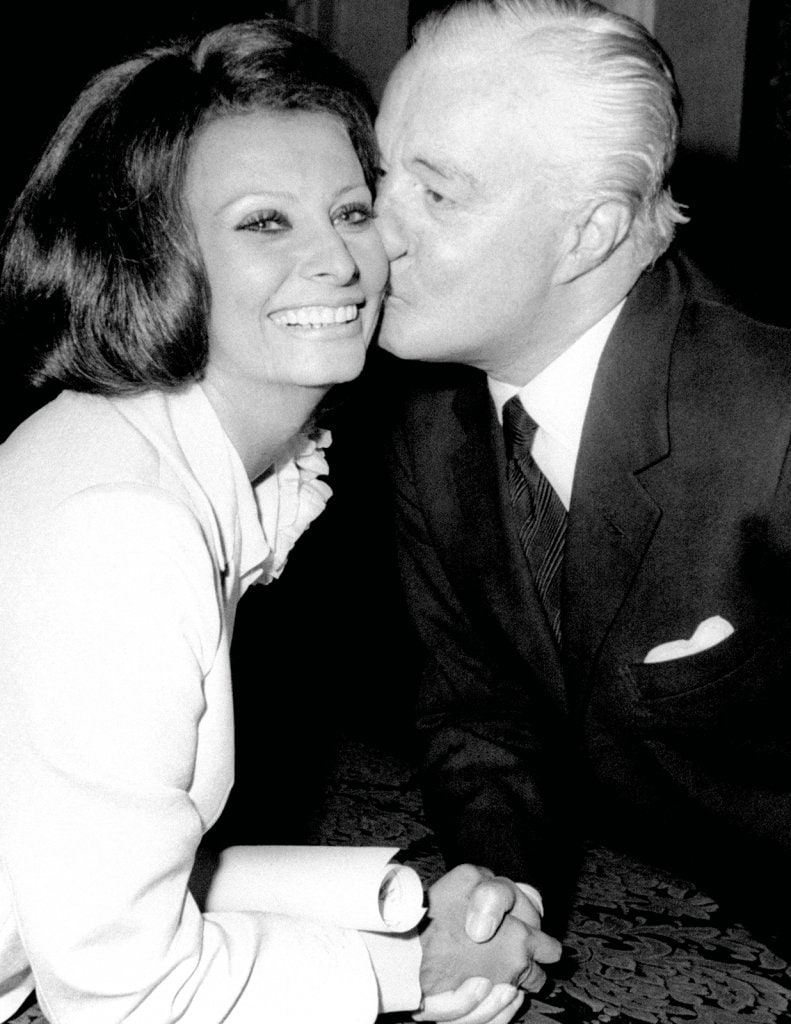

“Beautiful brown eyes set in a marvellously vulpine, almost satanic face,” was how Richard Burton, her co-star in a remake of Brief Encounter, described her. “Stupendously intelligent. Beat me at Scrabble twice.”

“Actually, that was a story my mother always used to tell me,” pipes up Edoardo. “He knew how much my mother loved the British accent and recorded tapes for her on how to pronounce words.”

Sophia sighs at the thought of this unmet goal: “I’ve been trying to have a British accent all my life.”

In The Life Ahead, she’s all but unrecognisable. She’s given herself over to the character physically: her face is angry and defeated, her hair wiry brown, her gait exhausted.

She plays Madame Rosa, a former sex worker and Holocaust survivor who looks after the children of “working women” while doing her best to stamp out the last glimmer of her humanity with hostile cynicism. When one of the children she takes in, Momo, calls her a b****, you’re inclined to take his side, but you also know the pair will form a bond.

The film is the third adaptation of La vie devant soi (The Life Before Us) by French author Romain Gary. Edoardo read it as a teenager and says Sophia herself needed no convincing, “because my mother likes to risk, she likes to push the envelope. She likes to do things she hasn’t done before.”

“When I read the story, I was enchanted,” recalls Sophia. “I knew it was something for me. Also, [I wanted] to do a film with my son.”

When I read the story, I was enchanted. I knew it was something for me. Also, [I wanted] to do a film with my son.

Sophia says she’s only interested in “special stories that really move me to tears, and it’s not easy to have that. We’ll wait.”

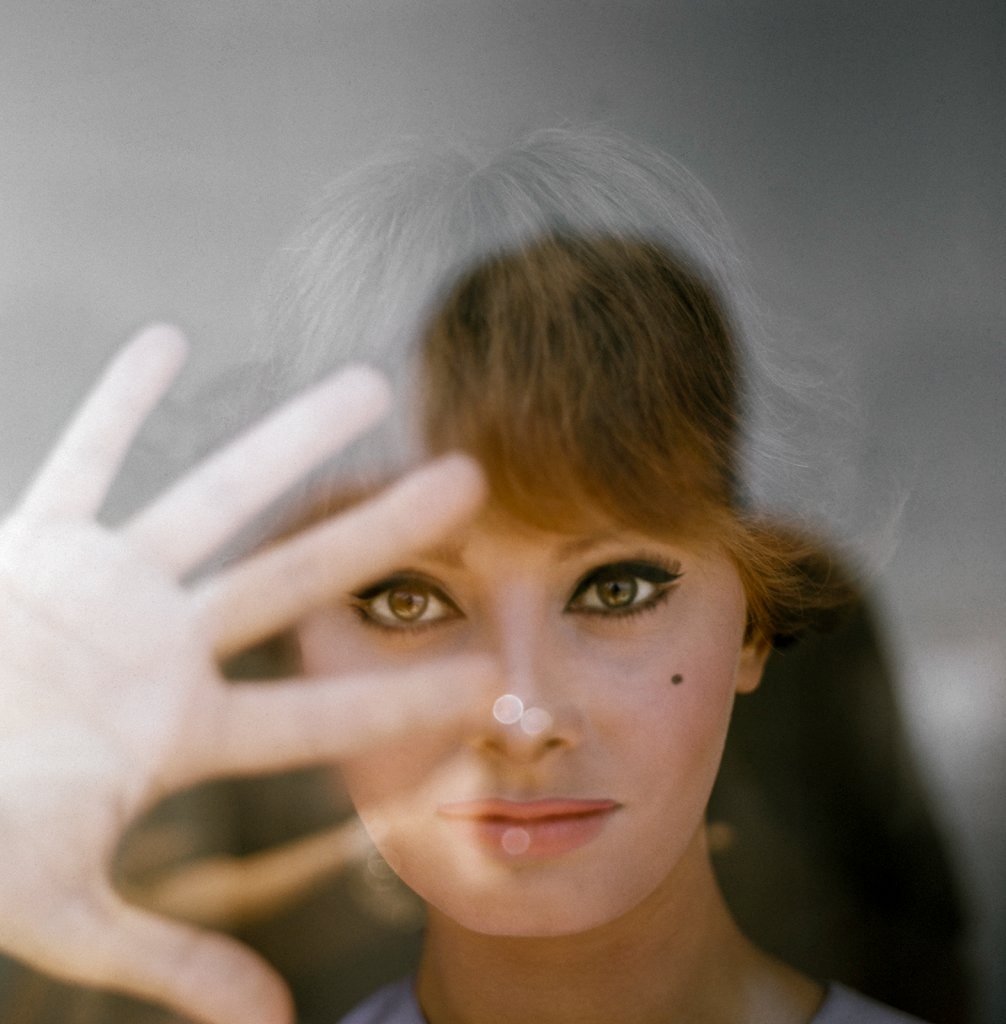

Without a video link, both you and I will have to imagine what she looks like in real life, aged 86. She’s dressed, she says, “normally”, but even in the time of pandemic, it feels like slander to imagine the woman who turned down the role of Alexis Colby in Dynasty defaulting to casualwear. We do know that two days ago, she cooked pasta alla Genovese, and a bit about the physical backdrop, which seems to sum up so much of how we’ve come to think of her: a grand apartment in Vieille Ville, Geneva, with tapestries and a long velvet sofa, antique tables crowded with framed family photographs, gold leaf accents and, of course, a grand piano – all items refugees from the 50-room Ponti estate outside Rome.

Sophia’s beauty in youth and opulent lifestyle later on can give the false impression that there was something inevitable about what she came to achieve.

She was born Sofia Scicolone in Rome in September, 1934, in a charity ward for unmarried mothers. She may have been just one of thousands of young, desperately poor girls, but her fatherlessness put her at a double disadvantage in a country that revered the Catholic church as much as it did its patriarchs. Her parents went on to have a second child, Maria, yet her father still refused to have anything to do with them.

Sophia’s biography describes growing up during the war – how, by the time she was eight, the family was starving, hiding from air raids in a rat-infested train tunnel full of “sickness, laughter, drunkenness, death and childbirth”. She never slept in a bed with fewer than three family members. When a piece of shrapnel grazed her chin (the scar remains), the family moved to Naples (she considers herself Neapolitan), then returned to Rome after the war, where her grandmother ran a bar from their living room.

In her youth, Sophia’s mother, Romilda, had won a Greta Garbo lookalike competition. Her daughter won a special award at the Miss Italia beauty pageant in 1950, aged 15.

She began scraping out bit parts as an extra in Italy’s growing film industry. Then she was spotted by Ponti. He changed her name to Sophia Loren and, in 1953, cast her as a lead in a film adaptation of Aida.

She spent her first pay cheque on her sister, buying the rights to her paternal surname from their father. “They gave me one million lire and that was the only money I had… With a lawyer I did everything I could to buy the surname for my sister.”

Intense fear of poverty and illegitimacy in general turned into a lifelong driving force. The word that comes up most often in Sophia’s conversation is “difficult”. “It’s very hard, when you have never had any opportunity to know what life is, what is going to go on, whether you can succeed – everything was a big question mark. And I really experienced the war. Bombing everywhere and killing everybody. It was really awful. And no money. No food. Just looking around for any opportunity which, for me, was very difficult because I was very young.

“I had to be positive because there were good opportunities for me to live this life that did not yet exist, but that I wanted to exist. I tried to do my best with what I had, in my body, in my head, just to be able to make it, to just go! Go, go, go!”

The memories are vivid. “I couldn’t carry on the way I was living at that time with nothing to look forward to other than what I was doing in my work, which was very little.”

Sophia says her most important teacher was Vittorio De Sica, who in 1954 directed her breakout film, The Gold of Naples, and precipitated her 13-film collaboration with Marcello Mastroianni and, eventually, a career in Hollywood.

She landed in Los Angeles with a five-picture contract from Paramount, but no English.

“I started by learning the script. What does that mean? What are they saying? Trying to understand what was happening around me, because I was completely lost. But,” she says proudly, “I was willing to learn, willing to go, go, go! Yes.”

It was intimidating shooting in the US with her heroes hanging around the studios. “It was really very hard for me to think of what I had to do in front of the camera with some of the people I had seen in films – my God! And in another language!”

She got a call from Charlie Chaplin to co-star in 1967’s A Countess from Hong Kong opposite Marlon Brando and hardly slept, worrying she’d never live up to Charlie’s expectations. “Never, never, never! But then, if you’ve had a hard life, you learn to cope with things you didn’t think you could before. Because I wasn’t only thinking of myself. I had ad big family behind me and they needed me badly.”

Working with Charlie “was a big moment in my life and when we finished, I cried my eyes out because it was one of the most wonderful moments of my career. He was teaching me the craft. My God! Charlie Chaplin! All this was inside me, but on the outside I looked very calm and pretended to understand every word he was saying.”

Sophia says it’s untrue that her husband ever told her to tone it down, but one of his cameramen certainly did, shouting during a screen test, “She’s impossible to photograph! Her face is too short, her mouth is too big, her nose is too long!” A charge of being “too much” follows her through her life, but her charisma and comic timing worked well in both Italian comedic and neorealist cinema.

She was always a force of nature, the opposite of Hollywood’s demure female ideal. In contrast, her predecessors, such as Grace Kelly and Audrey Hepburn, seem like cosseted anaemic princesses, and her contemporaries such as Marilyn Monroe like pleasers. Clark Gable, stiff and disapproving opposite her in It Started in Naples (1960), seems to be actively trying to shoot down her self-confidence with an arsenal of chauvinistic remarks.

How did Sophia have the confidence to withstand all this? “I don’t think I could have changed very easily,” she says. “If they had asked me to change something, I would have said, ‘No, thank you, I’m not coming.’”

On the charge of having irregular facial features, she laughs. “I didn’t have a terrible nose but, of course, when you make a movie, they like a face that’s very soft, very pretty, and I didn’t photograph as I was supposed to. But people got accustomed to my nose. I never changed anything about my nose

or my mouth, which sometimes I thought were too big, or my eyes – too big. Everything was too big in my face. But I became kind of accustomed to my features and they became a nice face, a nice image, and it just went on from there to now.”

She seems pleased about this. “Not bad. Not bad. It was not easy for me to go to America and be judged by so many people. But, generally, when I was asked to do a role, the role accepted how I was. I was not a monster! I had the same nose, the same face, the same body – which was kind of sexy.”

Besides, she really needed Hollywood, “because everything that I was doing in Italy was very small. I think I had to go. I think I had to learn English – I had to! And I did.”

To what extent does Sophia’s drive originate in her childhood poverty? “I think it is the only thing,” she says. “Of course! Because if it’s not that, it’s the other thing. And the other thing was, I didn’t want to go through the feeling of losing my battle. It sounds exaggerated but I started to be a kind of ‘fighter’ and I was willing to learn everything that was coming at me. Even the most difficult things. I always tried. Sometimes I didn’t succeed, but most of the time, with a smile on my face, I convinced people that I could do it. And I did.”

There’s a pause while she takes in these memories, then a faint laugh and an admission. “In a little while I’m going to cry,” she says.

“I am crying,” confesses Edoardo.

“My son is crying,” confirms his mother.

“We get very emotional, very quickly,” he explains.

“I know,” says Sophia, “because I started from nothing, really nothing.”

Her achievements still seem to astonish her.

“Sometimes it’s been a hard life, but it’s also been a wonderful life and I really hope that many girls have the same kind of experience because it is really incredible what I have – from nothing! Nothing! Nothing. The war, soldiers, bombing everywhere. It lasted a long time… With my grandmother, my mother, my sister – nothing else, just hope.”

It’s an awe-inspiring moment. “Hope. Hope. Hope! And I did believe in that. Yes.”

Text by The Times