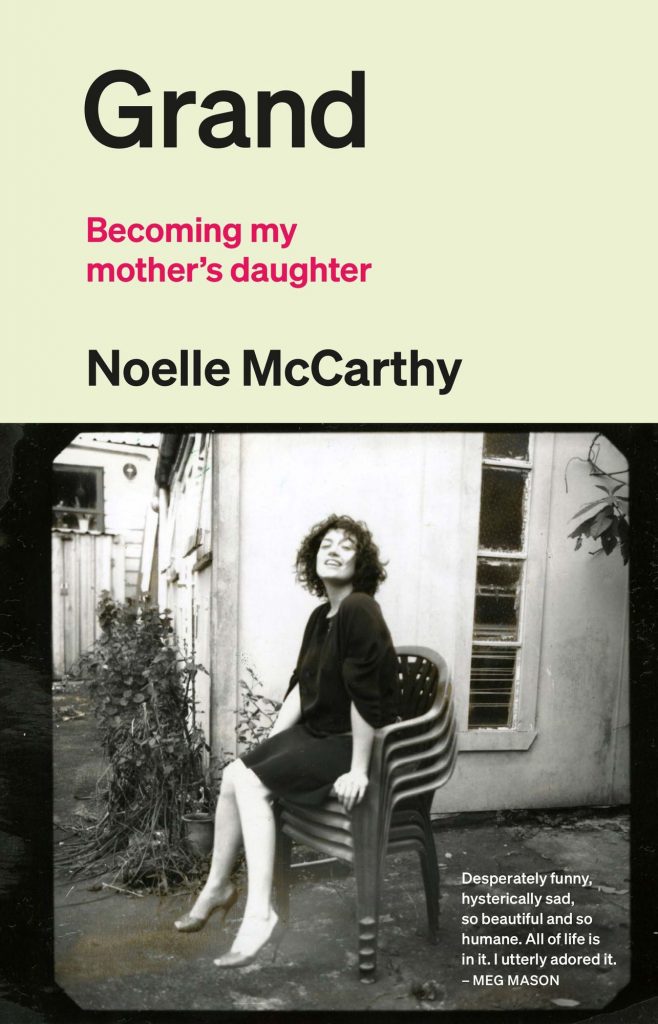

Journalist and podcaster Noelle McCarthy unravels brutal and profound family ties in her brilliant new memoir.

Some 200 pages into Noelle McCarthy’s spectacular maelstrom of a memoir, Grand – Becoming my mother’s daughter, unexpected peace breaks out.

It’s 2017 and we’re in Cork, Ireland, at a party celebrating the birth of Noelle’s daughter, Eve. Noelle and her husband John Daniell have already declared there’ll be no christening.

“Sure, you have to give people a night out,” her father, also named John, says. “They’ll only talk about you otherwise.”

At first the evening shapes up like so many others. There’s a relative in a kaftan with too much to say for herself, according to Noelle’s mother, Caroline. Caroline’s been pre-loading and is teetering on the brink of a tirade; tonight over Noelle’s perceived lack of gratitude for the enormous cake.

Then a cousin stands up and the room falls silent. He sings the opening lines to Leaving Nancy. There’s a yearning in his voice, hypnotic, and suddenly the whole room is swaying and singing under harsh fluorescent lighting. John McCarthy leads his daughter and the front-packed Eve to a space in the middle of the gathering. Caroline appears, fleet-footed.

“It’s just the three of us with Eve,” Noelle writes. “Strutting our little circle on the hexagonal function room carpet – me, Mammy and Daddy and their sleeping granddaughter.”

Noelle and I meet to talk about Grand on a sunny February morning at my apartment in Wellington. She sits on the floor, close to the recording iPhone. I perch on the couch, rudely forgetting to serve the morning tea she brought with her, because we’re writers and talkers and after some strong coffee, we’re away on a subject we both adore – memory.

The dance scene’s a precious serene moment in a swirling, majestic account of the alcoholism that plagued Caroline her whole adult life, and threatened to do the same to Noelle until she got sober in 2009. Noelle remembers how time seemed to pause, just then, for three generations of McCarthy women: Caroline, Noelle, and baby Eve. It was a rare détente in the fractious, sometimes violent relationship between Caroline and Noelle – a relationship that Noelle attempts to make sense of in the memoir.

“I knew something had happened there,” she says, of the dance. “I knew that I felt a great sense of belonging and contentment even though I was mortified and awkward.”

Noelle started drafting the memoir after the family moved from Auckland to Featherston in 2018. “My mother had been diagnosed with cancer, and I’d been making notes and thinking about everything, so I started writing little vignettes. And I noticed that the ones about my mother were more interesting… electric.

“One of the places I started was with my daughter. Once I became a mother, my relationship with my own mother shifted. Suddenly so much of the tension went out of it. It’s interesting to look back, now that she’s not here, and see that we had that relatively harmonious, mellow time. I started to feel the differences between her experience and my experience as a mother. It was visceral.”

Editor Vanessa Manhire is to be credited with the way the vignettes drift seamlessly – beautifully – between Noelle’s child and adulthood, between Caroline’s mothering of Noelle and her siblings and the earlier, secret births of two other babies (one died, the other was adopted out). The reader slips effortlessly in and out of the decades, between Ireland and New Zealand, never confused about time or place. The storytelling is as engrossing as a novel – Noelle pulls no punches in recounting her mother’s raging drunken behaviour and her own chronic alcohol blackouts during her high-profile years as an Auckland radio journalist and broadcaster.

“I like the irony of it,” she says, of the subtitle Becoming My Mother’s Daughter.

“I thought I was doing everything, for so long, in opposition to my mother. I thought she held me back. I remember thinking in my late teens that I’m never getting married because she can’t possibly come to the wedding.

“I had all that self-obsession and solipsism of a young person – that she had blighted my life – and then came the reckoning with my own drinking. I thought, I cannot believe this… is it the cruellest cosmic joke imaginable? I should have known.”

Becoming her mother’s daughter left Noelle terrified of passing on addictive traits to her own child. There’s a heartbreaking moment in the memoir, when she discovers she’s pregnant with a girl. Her instinctive reaction is one of dismay; an irrational fear that McCarthy women are destined for alcoholism.

She’ll talk to Eve about this, when Eve’s old enough to understand, she says. There’s a lot to talk to Eve about, I suggest, and she agrees. Caroline died in March 2020.

“I can already see my mother slipping from Eve’s mind. Even now, she knows her as a photo. I’m glad there’s a record. But there’s no way of dressing it up – if I put someone else in a book, that’s my act. And it’s not an act of autonomy, I’ve placed her there.”

I ask her whether she feels ready for the regurgitation of her own difficult period in the public eye. The memoir doesn’t shy away from accusations of plagiarism in 2008, or media coverage – including photos – of the fallout from excessive drinking.

“I’m 43,” she says. “I’m a grown up, I made a decision that it was worth it. What I love about a book is that you can always go back to the text. Everything I have to say – it’s all here. I’m protective of my family and my space but I’ll be open, without exhausting myself. I feel ready for it.”

What does her father think of the memoir? Aside from denying one claim that he once drank 16 pints, Noelle laughs, he finds it strange to be in a book.

“But he’s ordered lots of copies. My mother was such a powerful force in all our lives – it was a good thing to be able to talk about her, using the book as a starting point. We’ve had some good conversations off the back of it.”

Alongside the bruising truths, you can feel – on every page – Noelle’s respect for her mother. Caroline fought hard to have Noelle, and then her sister Sarah, enrolled in the best high school, refusing to accept an initial rejection.

“She was intelligent and she was frustrated, but she was fanatical about education. And in retrospective terms of becoming my mother’s daughter, that’s where she left her impact. That’s where she put her mark on us.”

Caroline associated County Kerry with her childhood, with happiness. Cork frustrated her intensely, Noelle says. The two of them took a trip to Kerry when Noelle was a child, to a religious festival called the Pattern.

“It came to me very late, this memory – most of the book was written. It was pivotal. I realised I remember her happiness. It was only when I look back that I saw how she intrepid she was. She didn’t even have a bank card or her own front door keys… but she got us down to Kerry.

“I just miss her. I miss her being in the world, for herself. That was the hardest – I realised only in her death that she loved being alive, she had a furious hunger for the world. That’s a truthful thing about her that I realised in writing the book.”

And in spite of the teenage dread, there was a wedding. Noelle and John married in France in September 2018. Her father fears flying, so never made it, in spite of Caroline’s promise to get him on the plane. Mary next door got Valium going to Bulgaria, she told Noelle. She said if he takes a couple of them, he won’t know what he’s doing.

“I can’t believe I have to get married without the public-facing parent,” Noelle writes.

There are a few challenges. Caroline is unimpressed with the heat, the camping ground, and, specifically, the absence of an off-licence. Eve falls over and gashes her forehead before the ceremony. No one can find the key to the cupboard where the wedding dress is being stored. But after the vows are spoken, Noelle recalls lines from the TS Eliot poem Burnt Norton:

At the still point of the turning world… Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is.