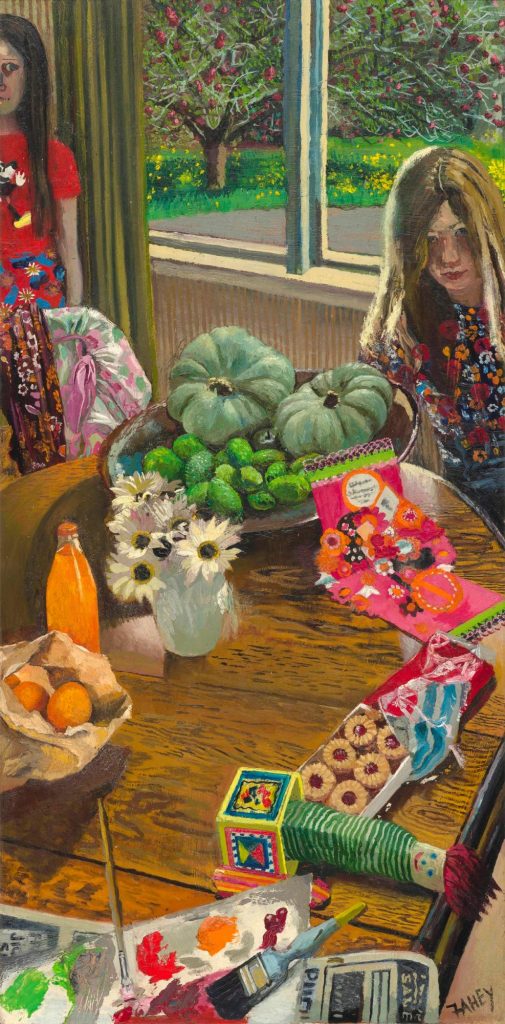

With her riotous depictions of domestic life, Jacqueline Fahey created a unique home for herself in the New Zealand art world. She talks to Dionne Christian about gender barriers, defying convention and why she’s still painting in her nineties.

Jacqueline Fahey’s rebellious spirit showed itself early. Now 92 and exhibiting new paintings, the acclaimed artist and writer still remembers being “expelled” from Timaru Girls’ High School kindergarten when she was just four years old.

It might have been because of an incident involving throwing the shoes and socks of older pupils into a swimming pool; that was surely compounded by her steadfast refusal to tuck her singlet into her underpants the way head teacher Miss Barr thought girls ought to.

Some 87 years on, we’re still policing how girls dress, while Jacqueline continues to defy convention. When we meet at her home in Auckland’s Grey Lynn, she’s wearing her trademark red lipstick and is trying to secure a pair of stunning earrings – a series of small petals in pyramid formation – one of which refuses to stay in her ear. She’s dressed in a black sweater embellished with large white pearls, a black satin skirt, embossed tights and sensible – albeit fashionable – shoes.

“We’re not doing the photos today,” I mumble, hoping she hasn’t taken extra time and trouble to ready herself for a shoot. “I know,” she replies, “I’m just dressed normally!”

PHOTO BY LUKE HARVEY

How I wish my normal was as stylish. Then again, once the interview finishes, I’ll race across town to pick a teenager up from school and go straight to pony club before heading home to make dinner and ensure the younger daughter does her hated maths homework. That life – working in the gaps between domesticity – is something Jacqueline well relates to. After all, she has long painted the world according to women.

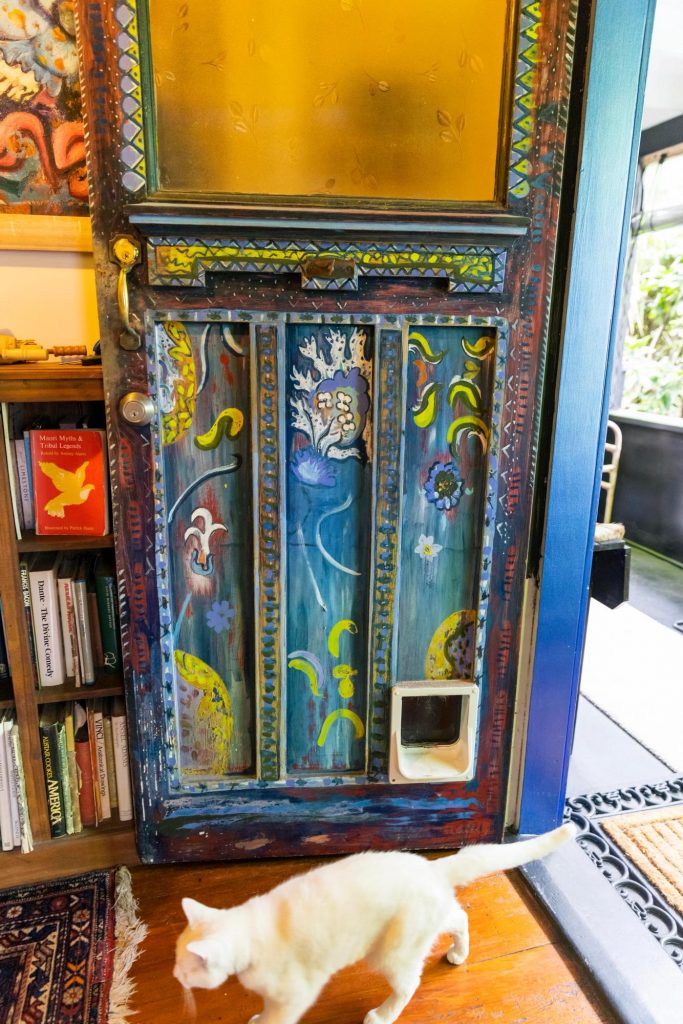

We sit at the solid wood dining-room table in the villa she shares with a snow-white cat and Emily, the youngest of her three daughters, and Jacqueline reflects on the kindergarten incident with a wry smile. Whatever the reason for her dismissal, she wrote in her 2006 memoir, Something for the Birds, “I was expelled, heralding a history of expulsions.”

Expulsions and leavings there may have been, but since Jacqueline first exhibited her paintings in a Wellington coffee shop where she worked part-time, having graduated from Canterbury University College School of Art in 1952, she has been a constant, sometimes controversial figure in New Zealand art.

With Rita Angus, she organised the first art exhibition in Aotearoa with an equal number of female and male artists (in 1964 at Wellington’s Centre Gallery); in 1980, Jacqueline travelled to New York on a QEII Arts Council Award to look at the realities of being a woman artist in one of the world’s toughest art markets. In 2007, two of her paintings featured in the major exhibition WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

Jacqueline has now been painting and exhibiting work for seven decades and jokes that she gets rediscovered every 10 years. The last time was in 2018 when Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū staged an exhibition of her work, then, the following year, the New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata exhibited her paintings in Suburbanites, which later toured to Auckland and Hamilton.

This time round, though, the gap is smaller and she has a solo show – a mix of older and new work – at a dealer gallery. She’s blunt about why.

“Because I need some money, so it’s quite straightforward. I thought, ‘If I want to go on living, then I don’t want to be behoven to anyone else,’ and what was happening was that I’d been generous about my paintings, not charging people much, and then I would see them coming up at auction [where they sell for high prices] and I would think, ‘Oh, f *** that for a joke!’”

I would see [my paintings] coming up at auction and I would think, ‘Oh, f *** that for a joke!’

PHOTO BY LUKE HARVEY

Every morning, she heads into the studio in the front room of her home where she spends two to three hours painting. She describes herself as a vigorous painter who once worked for four to five hours a day and says the one thing that has changed about her work is the energy she can bring to it.

PHOTO BY LUKE HARVEY

“I paint with quite a lot of energy and I don’t just fill in or fiddle… I had breast cancer four years ago and, of course, I couldn’t paint during that period. Inertia took over for a while but I wrote over that period,” she explains.

Eye surgery to remedy glaucoma meant seeing clearly again so Jacqueline picked up the paint brushes once more. She has long followed the example of her friend Rita Angus and integrated her life into her art. The painter’s equivalent of writing what you know.

In Something for the Birds, Jacqueline quoted the Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy: “Out of talk, appearance and manners I’ll make an excellent suit of armour; and in this way I’ll face malicious people without the slightest fear or weakness.”

So, instead of doing what many female painters of the 1950s and ’60s did and stick to landscapes, Jacqueline donned her suit of armour, continued working once married and mothering, and painted what surrounded her: domestic life, with three daughters, married to a well-known psychiatrist, Dr Fraser McDonald, whom she met at a party in a Wellington flat. By doing so, she was one of the first New Zealand artists to put women’s lives and experiences at the forefront of paintings which bristle with and revel in all the uproarious pandemonium of home life.

“Everybody who I went to art school with, it was all landscapes, as if they weren’t locked up in houses with their kids! You have to go to enormous effort to get out when you’ve got young children; you’re almost bolted to the spot!”

Everybody who I went to art school with, it was all landscapes, as if they weren’t locked up in houses with their kids!

Rather than “tidy away” household paraphernalia, as many might when painting a domestic scene, Jacqueline packed her art with the stuff of life: clothes to be washed or ironed or fought over, dirty dishes and remnants of meals, including good old Georgie Pie cartons, floral bouquets on sideboards next to fine china and books, the detritus of a child’s birthday party, toys to be put away and a mother looking more harassed than happy in 1986’s Happy Christmas.

Colour and chaos abound; this isn’t just art but social history – and politics – with an intimate view from the kitchen sink and every room between it and the front door. The emotions of the occupants of those rooms boil over – as in 1981’s My Skirt’s in your F***ing Room inspired by two of her daughters fighting over clothing borrowed without permission.

Having started studying art when she was just 16 and feeling compelled to paint, surely there were times when Jacqueline felt like walking out the front door, especially when she was told (often by other women) that she should not – could not – paint because she was now married, and husband and family should come before all else?

As she wrote in her second memoir, Before I Forget, in 2012: “I didn’t want to escape from my family, I loved them. I began to understand that what happened in my kitchen was as momentous to me as what happened in Queen Elizabeth’s banquet hall… Everything that made up my life automatically became part of my work.”

But Jacqueline stopped short of painting the patients she met while Fraser worked as a psychiatrist and the family lived on the grounds of hospitals such as Porirua, Mont Park in Melbourne, Kingseat and Carrington. She says it would have felt disrespectful and intrusive.

Jacqueline taught painting at the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts in the 1990s. At the time, more than half the students in the painting department were women, but there were the sometimes-uncomfortable realities of a supposedly comfortable suburban existence. She’s often included herself in her paintings; a silent witness to suburban atrocity or a vocal figure commenting on what’s taking place on the canvas.

Her new work is made up largely of what surrounds her now that, says Jacqueline, she is once more “rooted to the spot”. There are flowers, beautiful art and objects collected during her travels, the street outside, Emily, the cat.

“You don’t sit in old age, do you?” she ponders. “You’re standing in a bubble, really, in the middle of something and you’re not thinking in terms of how young or old you are. I don’t think I am old until somebody tells me I am, but I know I haven’t the energy I once had. That’s all I can say. I feel exactly the same except for the lack of energy and the caution that comes from that. As somebody said about creativity, you are eternal.”

Often her suit of armour had to be tough indeed. In the late 1950s, while pregnant with her first child, she produced the Suburban Neurosis paintings, which commented on the isolated existences of many women cut off from friends and family in new subdivisions. They were strongly feminist works, which may have been why they were turned down for exhibition at the then-influential Barry Lett Gallery.

Jacqueline destroyed all but one of those paintings, Woman at the Sink (1959) where a lone woman stands in a bare, brown kitchen, looking despondent as she washes dishes. The only hint that there could be a shred of hope is the woman’s vivid floral apron. Or maybe, sadly, it’s a memory of what the woman wanted to be. I tell Jacqueline it reminds me of the time my best friend came to stay and when asked to help with the dishes, she looked at the tea towel like it was a foreign object and told my mother, “I don’t do dishes. My mother says there will be plenty of time for that when I am older.” Jacqueline declares, “What a sensible mother that girl had.”

It angers her that, so many years on, women are still facing the same issues – exacerbated and made clearer by Covid-19 and its lockdowns. Of those who have lost jobs, the majority are female; the bulk of domestic responsibilities, especially home-schooling children, has fallen to women, even though they may themselves be working at paid employment from home; domestic violence has increased.

When a young man commented to her recently that she had to admit things had improved and changed for women, Jacqueline says she asked him what planet he was living on. It’s been much worse, she says, for working-class women.

“But we don’t have [social] classes here, do we? There’s no word for class in New Zealand, so they tell me. That’s the biggest myth of our national identity, it’s rubbish.”

Her politics, she says, are ever more strident. “More so in the sense that I think without justice and equality we are doomed, the human race will be something that happened once. Climate change is part of it; it’s worsened by inequality.”

Jacqueline Fahey’s Defences Against the Void is on at Gow Langsford Gallery in Auckland until May 15.