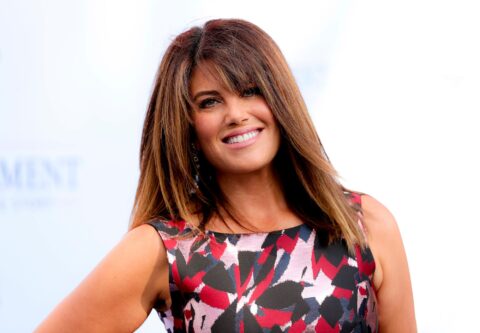

Green Party co-leader and mum-of-six Marama Davidson opens up about her vision to empower the voiceless and the collective spirit that gets her through.

“Mōrena!” says Marama Davidson over the phone from her office at the Beehive. It’s 7.30am on a Wednesday and the Green Party co-leader has already been at work for an hour. She’s busily preparing for two select committee hearings – one on housing and another on domestic violence – but she’s managed to squeeze in our interview between that and her ministerial briefings.

Back home in Manurewa, Marama’s whānau are getting ready for the day. Lunches are being made, sports gear organised, after-school activities and dinner plans nutted out. The Davidson kids are used to Marama not being there, but that doesn’t make it easier, says the dedicated māmā of six, who entered Parliament in 2015 and quickly made a name for herself due to her staunch advocacy around social justice issues.

Marama has had six years to adjust to the commute between home in South Auckland and work in Wellington, but since becoming Minister for the Prevention of Family and Sexual Violence and Associate Minister for Housing (Homelessness) after last year’s general election, her workload has stepped up another gear. While the portfolios have given her an even greater platform to make a difference – and she’s determined to see real change during this parliamentary term – the demanding roles have undoubtedly taken a toll on her loved ones.

“The default setting in our family is that I’m not home,” she says. “And when I am there, it’s pretty much just seen as a bonus. Everyone has got used to it being like that because they understand I have a job to do and they know they’re all part of it, actually.

My work is a shared family project, I’m just the one out the front.” Marama shares her home with her husband Paul, who’s a social housing manager with The Salvation Army, and their three youngest children, Manawa, 15, Horouta, 13, and Teina, 12. The couple have been married for 25 years, and also have three older children – Heria, 27, Annalisa, 25, and Dekota, 24 – who all live nearby.

During the week, Marama stays in the capital with her sister. When Parliament is sitting, her days are long – she rises at 5.45am and is typically at work until nearly midnight. She usually returns to Auckland at the weekends, but often with a full schedule of community events to attend, not to mention her “weekend bag” – a briefcase full of reading material to prepare for the coming week. She knows some more experienced ministers can nail their weekend bags in a few hours, but for her, it’s often up to 10 hours of work.

“I take a meticulous approach,” she says. “I read every single line and every single word. I haven’t got into my flow yet, and I feel anxious unless I’ve managed to get through it all.” Politics is not a lifestyle she’d recommend, she says frankly.

“It’s actually quite ironic when you think about it. You put a whole bunch of MPs into a really unhealthy living situation and you expect them to make good decisions,” she says, when asked if she’s one of those people who can survive on little sleep.

“I would absolutely love to get more sleep.”But Marama (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou) isn’t the sort of person to walk away from a challenge, and despite the impact of her mahi on her home life, she’s more determined than ever to use her position for good. Since entering politics six years ago, she’s become known for her strong political advocacy on all issues concerning tangata whenua and social justice. And since taking on the ministerial portfolios for domestic violence prevention and housing, that responsibility to help those who need it has become even more pressing.

It should be no surprise Marama followed this path – before politics she worked for the Human Rights Commission, the Owen Glenn inquiry into violence, and Breastfeeding New Zealand. She’s also a qualified aerobics instructor. Activism runs in her veins – her parents (mum Hanakawhi Nepe-Fox and actor dad Rawiri Paratene) were loud campaigners for te reo Māori, themselves and their parents the victims of a system where their language had been “beaten out of them”

.Marama’s most recent work has been around the prevention of domestic harm, and last month she announced the launch of a national engagement process on the prevention and elimination of family and sexual violence. Feedback has been invited from people and organisations around the country, which will inform the creation of a national strategy and action plans.

Marama is determined that her legacy, no matter who comes along after her, will be a lasting framework that will help women from all walks of life. While family harm can affect anyone, there’s no escaping the fact that wāhine Māori are still disproportionately represented in the data. More than one in three are survivors of family and/or sexual violence, which is why it’s imperative any changes are made from a whānau-led, te ao Māori perspective, says Marama.

The most important step is speaking to women and whānau to hear their “lived experiences”, she says. She rebuts recent criticism over a hui with the Mongrel Mob. Nowhere is off limits when it comes to gathering stories.

“For years and years I’ve worked with women who belong to gangs, and it was really important and will remain important to me, because they just feel completely dehumanised and stigmatised,” she says. “These are women who themselves have been at the forefront of harm, including from gangs and gang members who need to be accountable for that harm.

I need to listen to them, I need to see them as holding the keys to the solution, to a better life

“I need to listen to them, I need to see them as holding the keys to the solution, to a better life,” she adds. “What is it that we need to do to support them – and all women – to feel that they have control and can make safe, good decisions for them and their children?”

In 2018, Marama bravely spoke out about her own experience of childhood sexual abuse. She tells us that family violence has also had an impact on her life, but it was her experience on the Owen Glenn inquiry into child abuse and domestic violence that left the biggest mark.

“The stories of intergenerational harm and hearing those voices first hand was a really important starting point for me in this work.” Marama says a huge part of her focus is how to make change that will last beyond this government’s three-year term.

“Governments have had multiple attempts at trying to stem violence, but it hasn’t worked. So, we’re trying to do something that is dramatically transformational. The whole vision is an Aotearoa that is safe for everyone.

“For decades, we’ve largely operated in silos and not properly empowered and resourced community-led solutions, and we’ve focused on responses rather than prevention,” she says. “It’s those key things that we’re trying to shift here. It is going to take a lot of work and long-term planning.

“It’s a massive responsibility,” she adds. “The system change that we are trying to put in place is not going to have outcomes for quite some time. This is generational work that we are talking about here. The dream is that you will put that all down and then, no matter who comes along, it will be in place and it will make a difference.”

Marama slips easily in and out of politician speak, but there’s no doubting this woman’s authenticity. She knows her voice and work gives her unique privilege and power, and she’s determined to use it to help others.

There are two words that she uses a lot during our interview. One is “collective” and the other is “sacrifice”. Everything she does is for the collective – whether that’s whānau, her community or those in Aotearoa who haven’t felt fairly represented – and that’s what makes the sacrifice worthwhile. She tells Woman she’ll continue speaking out when she sees racist, classist behaviour in Parliament – in March, she called out National MP Nicola Willis for perceived undertones to her comments on safety in central Wellington.

“It’s that racist, classist, dehumanising and stigmatising narrative that has not helped,” she says. “It hasn’t helped violence or crime, and it has not helped building community bridges. A big part of my work and my role as minister both in housing and violence is to stand firmly against that approach, which has actually made things worse, you know.”

Marama is unequivocal about how she’s managed to make her career work while raising a large family.

“Support. It’s all about having incredible support, and I know that’s the same for every other politician who has dependents. You just can’t do it without other people in the background making it possible for you.”

It’s all about having incredible support… You just can’t do it without other people in the background making it possible for you

PHOTOS SUPPLIED

There have been some huge personal sacrifices for her mahi – she misses birthdays, sports games, kapa haka performances – but Marama credits her “amazing” husband Paul for holding down the fort. He is the go-to parent (“If I turn up on the sports sidelines or at school, people are shocked, because it’s Paul they’re used to seeing. I’m just never there”), but Marama is also hugely grateful to her oldest daughter Heria, who has always helped run the household, too.

Until late last year, Heria, her partner Rajan and their 18-month old daughter Raeya – Marama’s treasured moko – lived at the Davidson family home too, but even though they’ve now moved into their own home, the relationship hasn’t changed. When Paul is busy at work, Heria steps into his shoes and helps with housework and cooking.

“Heria is actually the person who holds down the house and the kids for us a lot,” she explains.

“The two big boys are at college, so they can walk home, but Teina, she has training and sports and all sorts, so there’s often a lot of running around for her and Heria does that. We’re very lucky.

“We have meetings about the events that are coming up and how we can share around the responsibility, so it’s not even about my family supporting me, it’s about my family and our collective approach to supporting each other.”

It’s a very te ao Māori view, but Marama notes her gratitude for it, adding that these sorts of “tools and systems” were interrupted by colonisation and urbanisation.

“For most people, being able to keep your family together in this aspect is really difficult. You know the sort of modern, city style of living doesn’t necessarily bring us closer, so we have to work really hard at that and for most families that is a struggle.”

Marama admits that even though the children are used to their mum’s absences, that doesn’t always mean it’s easy. Recently, it started to become clear her youngest daughter Teina was struggling with the time apart. Marama had to do “damage control” – a weekend of one-on-one time and a commitment to make more time for her going forward.

“I can’t do that often, but it’s about building it in,” she says. “I realised things were getting a little tetchy there, so I thought, ‘OK, something needs to change here.’ So I planned to have a whole weekend with her, just she and I stole away for a little daughter time and that was beautiful. I won’t be able to do that very often, but I will try.”

Marama says her entry into politics has been hardest on Teina, who was just six when her mum became a list MP after 10 years with the Human Rights Commission.

“She was my little mate, she would come everywhere with me because she was at home for the longest. So it was a bit of a shock to her the first week.” And hard on māmā, too, no doubt. “Oh yes, but that’s the norm, isn’t it, when parents have to work. Every parent knows what that feels like.”

As well as family time, something else that’s been sacrificed is Marama’s efforts to speak only te reo Māori with her little ones. When Teina was born, she made the decision to converse only in te reo with her youngest. But the reality of a hectic political life meant that fell away when Marama started spending many nights away from home each week. Paul, who is Pākehā, does his best with “words here and there”, but Marama dreams of a future where her whānau speaks only in te reo.

“It was going really well and I never spoke a word of English to her. It was really cool. Then I became a politician and that just completely broke and it was a real shame, so that’s a massive trade-off, a massive sacrifice. I’m hoping we can get that back at some point.”

But at the end of the day, her family is why she makes these sacrifices.

“I’ve always said that I’m here as part of a collective,” she says. “That’s not just my family, that’s actually the community who put me here and who I represent, and often those are the people who don’t get a voice, the people who feel that they are not represented in places of power.”

And with that, Marama’s assistant tells us it’s time to wrap up. Marama is off to front a select committee for what she knows will be “a grilling”. She doesn’t dread these things, though – in fact, she relishes the chance to be part of change.

“I am really looking forward to them. The system is designed to keep us accountable and answer questions, so I think these are good opportunities for people to engage with what we are trying to do and what our goals and visions are.”

And when the bruising life of politics gets too much, Marama knows she can head home to her loved ones, who restore her wairua before she heads back to Wellington.

“I don’t have any time for anyone else except my family, you know? All I want to do is work and family, that’s it, that’s all I’ve got time for.

That is basically the mental health plan – to reconnect with people and places that make you feel safe, warm and loved

“That is basically the mental health plan – to reconnect with people and places that make you feel safe, warm and loved, and it’s also remembering to keep things in perspective and stay focused, and it’s the collective who help me do that.”