More single women than ever are opting to conceive via sperm donor. Sarah Catherall speaks to three of them about their experiences.

Charlie Pilcher

On a cold Monday afternoon, Charlie and Erin Pilcher are having a day at home together, away from work and childcare. Two-and-a-half-year-old Charlie nibbles on a jam sandwich and jumps down from the table to dance around the living room.

The mother and daughter then look over a picture book published by the Donor Conception Network: Our Story: How We Became a Family. Charlie, a cute blonde-haired wee girl, points to the fictional mother in the book, and says, “That’s Mummy.”

On another page, Erin points to a group of men and asks, “Who are they Charlie?’’, to which the wee girl pipes up, “Donors”.

There’s no mention of Dad in this happy family scenario. Erin says, “Charlie already knows she doesn’t have a dad. At some stage, Charlie will be told about her donor, but the thing is, I am her parent and I am doing this solo.’’

Erin is one of a rising number of independent New Zealand women signing up for fertility treatment on their own. Many of those who go on to have a baby opt to be known as “single mothers by choice”.

Over the last three years, the number of single women seeking donor sperm has tripled: there are now more than 300 single women on the waiting list.

Last year, of the 400 women inseminated with donor sperm at Fertility Associates, 160 were single.

While Charlie plays with her toys, Erin openly shares her journey, hoping it might inform and inspire other childless single women wanting to be mothers. When the Wellington public servant turned 37, she had a crisis, realising her expectation that she would be a mother was slipping from her grasp.

Erin grew up in a small town with a large family, and always thought that would be her journey, too. But she hadn’t met the right man who might be a potential father.

“I sat in my GP’s office and started sobbing, saying it had always been my dream to be a mother, and here I was at 37, thinking that would never happen.’’

Erin was surprised by her GP’s reaction. Rather than nodding sympathetically, her doctor handed her a tissue and told her there was another option to being childless: Erin could find a sperm donor and have fertility treatment to have a baby.

Erin met with a doctor at Fertility Associates, where she had a bunch of tests and was told her egg reserves were low, and that the chances of getting pregnant via IUI (Intrauterine insemination, when sperm is placed directly into the uterus) were 11%, based on her age and egg reserves.

If she went through IVF (using an embryo created with her egg and donor sperm), the chances were about 25-35% that she would fall pregnant. But Erin wanted to go through IUI, as it was cheaper and less invasive. She was told she would have to wait for up to 22 months for sperm.

In the meantime, though, a friend approached her and said her husband loved being a father to their son and was willing to help Erin by being a donor. His sperm had to be frozen and tested, and both parties had to go through counselling, which Erin – who was 38 by then – paid for.

“We needed to have a robust discussion around boundaries,” says Erin. “I’m the parent and he would be the donor. There would be no expectation of anything more whatsoever.’’

On the day of the insemination, Erin told her workmates and her male boss where she was going. “It was a regular Friday morning, and that afternoon I was back at my desk.’’

A fortnight later, she got the phone call she had dreamed of. “They told me I was pregnant based on a blood test. I burst into tears and told my donor and all my family, and friends at work, and everyone was so happy for me,’’ she recalls.

Her mother, two sisters and three friends were at Charlie’s birth on January 1, 2019.

Since then, Erin has faced no stigma, and tells anyone who wants to know that Charlie came about thanks to a donor. “I didn’t have to wait for a guy who would control my life and my body. I make all the decisions about Charlie, and I like that as a woman, I could make that happen.’’

She regularly sees her friend, the donor and their son, who is now five. One day, Charlie will find out that they are genetically connected.

“Then I hope for Charlie it will feel like catching up with an uncle and cousin,’’ shares Erin. “I do think that there is so much diversity today in what makes a family, so women like me are going to be increasingly common.’’

There’s so much diversity today in what makes a family, so women like me are going to be increasingly common.

According to Dr Simon Kelly, medical director at Auckland’s Fertility Associates, single mothers having babies on their own are the fastest growing group at the fertility clinic.

“Lesbian couples and heterosexual couples [seeking fertility treatment] have remained fairly stable. The growth has largely been driven by single women,’’ he says.

“There have always been demands for sperm donors but it’s the demand from single women that has dramatically increased over the past few years.’’

At any Fertility Associates clinic, single women typically wait for two years for a sperm donor, and then either use their own eggs or eggs they have frozen to undergo fertility treatment.

Simon says they’re often women in their mid-to-late thirties, and often career women who have either not found the right partner, or they have recently ended a relationship and are worried about finding a new partner to start a family with.

The biggest hurdle to overcome is finding sperm. Because there’s such a long waiting list, women like Erin, who find their own personal donor (subject to legislative approval), can speed up the process.

Another phenomenon at the clinic is the rise of “social egg freezing” – women paying to have their eggs extracted and frozen so they can have a baby either alone or with a partner in future. The number of women freezing their eggs has tripled at the clinic since 2017, when 60 women had their eggs frozen.

When women freeze their eggs, doctors discuss with them how they can have a baby on their own if they wish to. Then those who want to get on with it, often go on the waiting list for a sperm donor.

“It’s a social phenomenon that an increasing number of single women are coming in for fertility treatment. We are seeing the first generation of women who are truly able to plan their own fertility, and that’s exciting.’’

Modern family

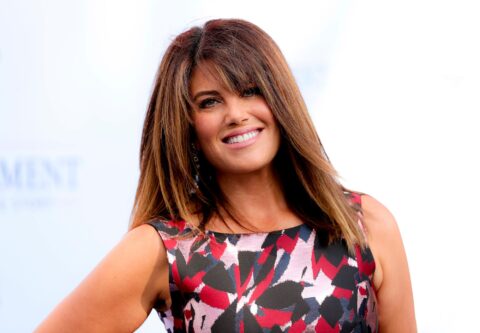

Carla O’Neil was 35 when she froze some eggs. Today, she calls her four-year-old son Hunter “my $30,000 baby’’.

PHOTO BY PETA MAZEY

Talking via Zoom from her home on Auckland’s North Shore, 44-year-old Carla has put Hunter to bed and is getting ready for work for the next day. She has a busy, hectic life as general manager of an event management company while Hunter is at full-time daycare.

Carla had been married and then divorced in her twenties and spent her thirties focusing on her career. “I didn’t find anyone I wanted to have a child with. I also wasn’t sure whether I wanted a child,’’ she says

At 35, she visited a fertility clinic and was told her that her egg count was low, so she froze some eggs.

She was 37 when she decided to take action and seek a sperm donor via the clinic so she could have a baby. Lucky for her, she had four donors and she chose one – a man with ties to South Africa, where she is from.

Carla went through IVF, had three embryos, became pregnant with one, but lost the baby at 11 weeks due to a chromosome disorder.

“It was really tough. I had been so excited about it. It took me a while to get over it,’’ she says, fighting back tears.

At 38, Carla picked herself up again and decided to thaw another embryo.

“Hunter was born three months before my 40th birthday,’’ she says, smiling. Carla decided she didn’t want any more children, so she donated the remaining embryo for testing.

“It’s so crazy what science can do to help women like me. But I did go through a lot and I had people asking me why I was doing this on my own.’’

Hunter knows he doesn’t have a father. At 18, he can choose to meet the donor, which Carla is fine with.

“Hunter is such a cool, smart kid and very much a wanted child. I love watching him grow. At the dinner table we always share the favourite part of our day, and tonight he said, ‘My favourite part was spending it with you, Mum’. We’ve got such a tight bond and I’m lucky that I’ve had this opportunity to be a mother.’’

We’ve got such a tight bond and I’m lucky that I’ve had this opportunity to be a mother.

Carla agrees it’s a costly option, though, for women who can’t afford it.

Going it alone

That’s the case for 39-year-old Kim, who lives in Wellington and is desperate to have a baby. She spent her twenties and early thirties travelling, and never met a man who was potential father material.

Six years ago, Kim was a surrogate for a gay couple who were friends. It was “a home job’’, where she inseminated sperm into her when she was ovulating.

They had to go through the legal process to confirm the surrogacy and she now has a five-year-old biological daughter whom she sees a couple of times a year.

“I thought that would feed my maternal instinct, but it didn’t. I thought it would be good for my system to have a pregnancy, too, so there was an element of selfishness to it.’’

Since then, Kim is now trying to get pregnant each month on her own, aided by a personal donor, another gay man.

“I just can’t afford to pay the clinic fees,’’ she says. Over the past six months, Kim has caught up with him monthly when she is ovulating. He provides sperm and she inseminates herself. For two weeks a month, she doesn’t drink alcohol and she regularly checks her basal body temperature and cycle, and urinates on pregnancy test sticks. Kim thinks she has about a 10% chance of falling pregnant each month, based on her age.

Fertility experts have warned there are risks with using DIY sperm donors, citing the 2019 case of “Tauranga Tony” (whose real name is Tony Ross) who donated sperm to a large number of women without telling them about his other donations. Fertility clinics limit donations to five to reduce the risk of inadvertent incest or inherited health problems for children.

Kim has a good relationship with her donor. Looking ahead to her 40th birthday, she says: “I really want to be a mother. I feel sad that I might not be able to. I’ve even got friends holding onto their baby gear for me. I’d really love to think that I’ll be a mother when I’m 40.’’