To know or not to know, that is the question for film-maker Lillian Hanly. She tells Sharon Stephenson about living with the prospect of Huntington’s Disease.

“A flip of the coin” is how scientists refer to Huntington’s Disease (HD). Because if one of your parents has the fatal neurodegenerative disease, then you have a 50% chance of inheriting it.

Tails, you’re OK; heads, you face a progressive disease that causes parts of the brain to die slowly, resulting in uncoordinated body movements, slurred and eventual loss of speech, psychiatric issues, dementia and ultimately death.

Lillian Hanly was in Year 10 at Auckland Girls’ Grammar School when her birth mother, Tamsin tested positive for HD in 2008. Tamsin sat Lillian and her two brothers down to explain what would happen, which was a bit like watching a gift you don’t want being unwrapped, says the now-27-year-old.

“I’ve never felt alarmed or worried about myself having HD because we’ve always been open about discussing it,” says Lillian. “My family is also in the privileged position of having late onset HD, which means possibly not showing symptoms until we are in our forties, which is when Mum was diagnosed. So I have time to find out if I’ve got it. But I felt sad for Mum and what she was about to face.”

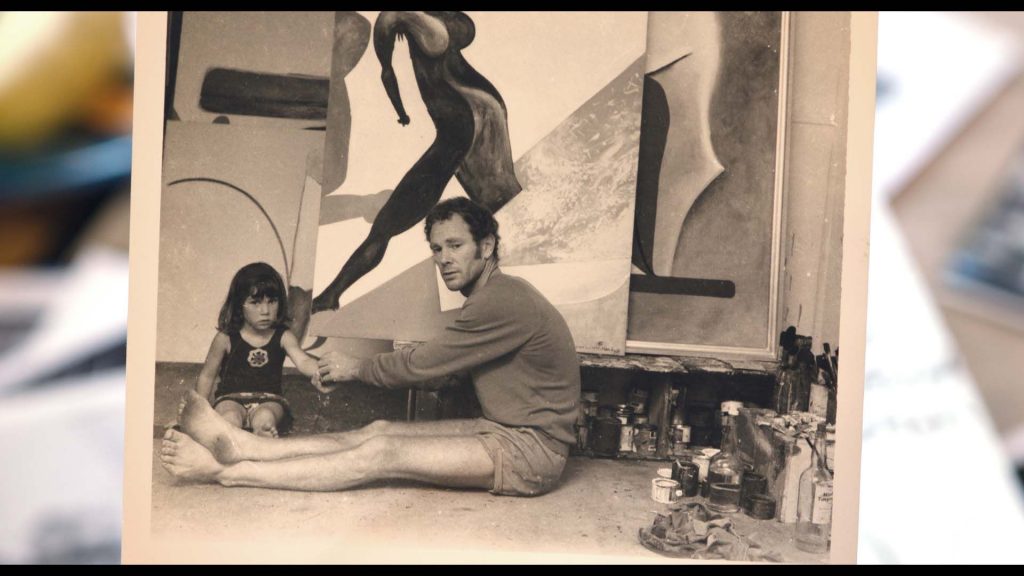

The shadow of the disease had previously fallen on Lillian’s extended family. When Lillian was 10, her grandfather, renowned New Zealand artist Pat Hanly, died of HD, and her cousin Micheal later found out he carried the mutant gene.

IMAGE: Gil Hanly

For Lillian, who works in the press gallery at Parliament as a TVNZ political producer, the question of whether or not to get tested – and the life sentence it could bring – has always hung over her.

“I’m fascinated by the choice: do I or don’t I get tested? Do I find out now or wait until I’m ready? Because once you’ve opened that door, there’s no shutting it.”

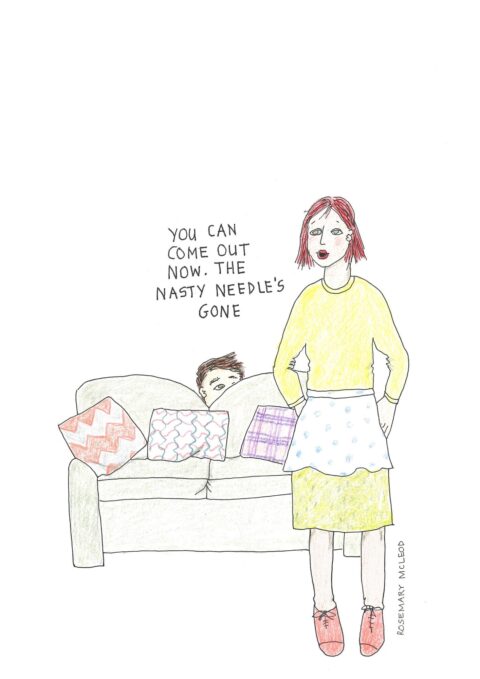

So fascinated was Lillian that she made a documentary about it. Fifty Percent, which is part of the 2021 Loading Docs series, explores this life-changing decision and the impact it can have on a person’s loved ones.

In the short film, Lillian talks to members of her family – some who have HD, some who don’t and some who don’t want to know – about taking the test.

“We look at the tension of finding out and whether I should just live my life without knowing, which could, of course, affect decisions such as moving overseas or having children. Because while I’ve always wanted kids, there’s the whole issue of giving them a 50% chance of having this disease,” she says.

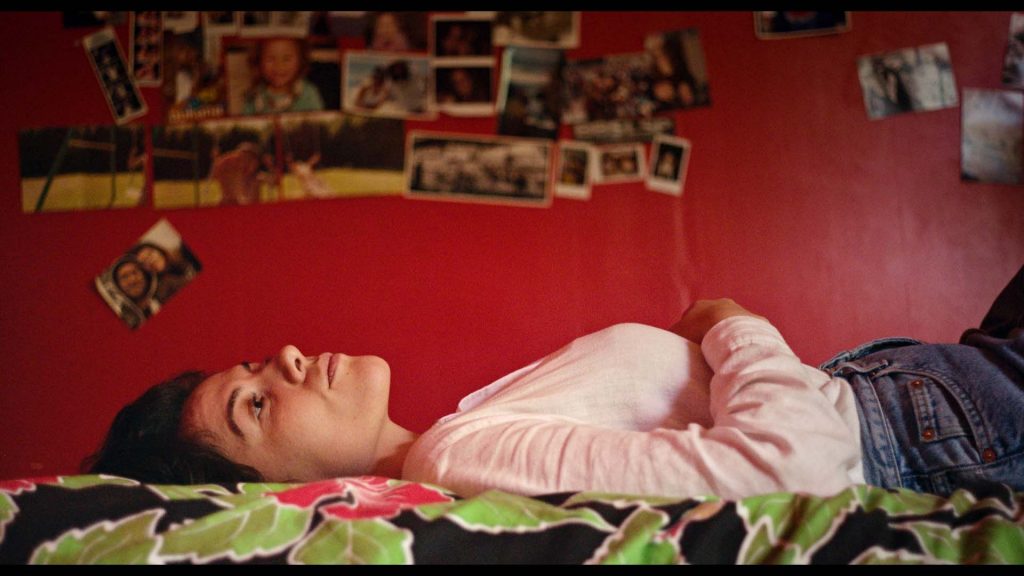

In some of the most poignant scenes of the documentary, Lillian talks to her university lecturer mother about her failing health, and her partner Farzad Zamani, who she’s been with for four years. When Lillian tells Farzad about living with a “ticking time bomb”, the softly spoken urban designer admits pain is part of life: “If you are a perfect body, you never understand the beauty of care, you never understand the beauty of support, you don’t understand love, because in these kind of situations, you really see if someone loves you and wants to stay with you and go through the pain with you.”

Speaking from the Wellington flat she and Farzad moved into last year, Lillian says it was important to share these difficult conversations that “aren’t always seen in mainstream media”.

“I also wanted to show how my family has embraced this disease. That even though they might or might not have it, they’re still living and loving life.”

It’s a family Lillian describes as “complex”. She was raised by Tamsin and her partner Leonie in a rambling Mt Eden villa that features in the film.

“When I was seven, they split up and Leonie repartnered. Leonie is Māori, but both my mums spoke to us in te reo, so that was my first language.

“I also have two Māori brothers.”

It was, she says, an idyllic childhood.

“I had three parents, so three very strong pillars of support. I was bullied a bit at school for having lesbian parents, but apart from that, I’ve always felt loved and supported.”

Lillian was also close to her maternal grandparents, artist Pat and his wife Gil Hanly, a photographer. Coming from such a creative family, it was inevitable she would pursue a career in the arts.

While studying media studies and history at the University of Auckland, Lillian started working at student radio station bFM, where she became news director. That led to a role at Newshub’s The Hui, where she worked with “one of my heroes” Mihingarangi Forbes.

“I love interviewing people and helping to reposition and reframe the conversation, especially around Māori issues,” Lillian says.

After a trip to visit Farzad’s parents in Italy early last year, the pair were set to move overseas. But when Covid-19 derailed their plans, they relocated to Wellington with Farzad’s job.

Lillian had just landed the TVNZ role when her proposal for Fifty Percent was accepted by Loading Docs. Making the 10-minute film was fitted into evenings and weekends, with the bulk of it shot over Anzac weekend.

Ask Lillian how her mother is doing now, and she’ll inhale deeply. “She’s gets tired more easily but is still working. I’ve noticed things like the involuntary tapping of her foot and the clicking of her tongue is increasing.”

There’s still such a stigma around HD, which Lillian is hoping her documentary will go some way to deconstruct.

“Mum is often refused alcohol at bars because they think she’s drunk,” says Lillian. “Once, at an airport, she was told to ‘sober up’ before getting on the plane by the check-in woman. It was 7am and she hadn’t been drinking! We told the woman about the HD but she wouldn’t budge. That really upset me.”

So will Lillian ever get the test?

“I am ultimately on the side of getting tested,” she says. “There’s so much research going on all the time, but you can only be considered for a drug trial if you know your gene status. However, I’m not quite ready to open that door just yet. I’m currently living my best life and I don’t want to taint that.”

What is Huntington’s Disease?

Sometimes shortened to HD, Huntington’s Disease is an inherited brain disorder that causes cells in specific parts of the brain to die, resulting in impairment of both mental capability and physical control. It’s a genetic disorder caused by an expanded gene. Everyone has the gene, but those who develop the disease have a longer version of it. The expansion causes the gene to not work properly and eventually results in neurodegeneration.

Medication can help to improve the movement and psychiatric symptoms of HD, but there is currently no cure. It’s estimated around one in 8000 people carry the gene, which affects men and women in equal proportions. In Aotearoa, it’s believed the prevalence of HD is higher among Māori. On average, HD patients live for 10 to 30 years after the initial appearance of symptoms.