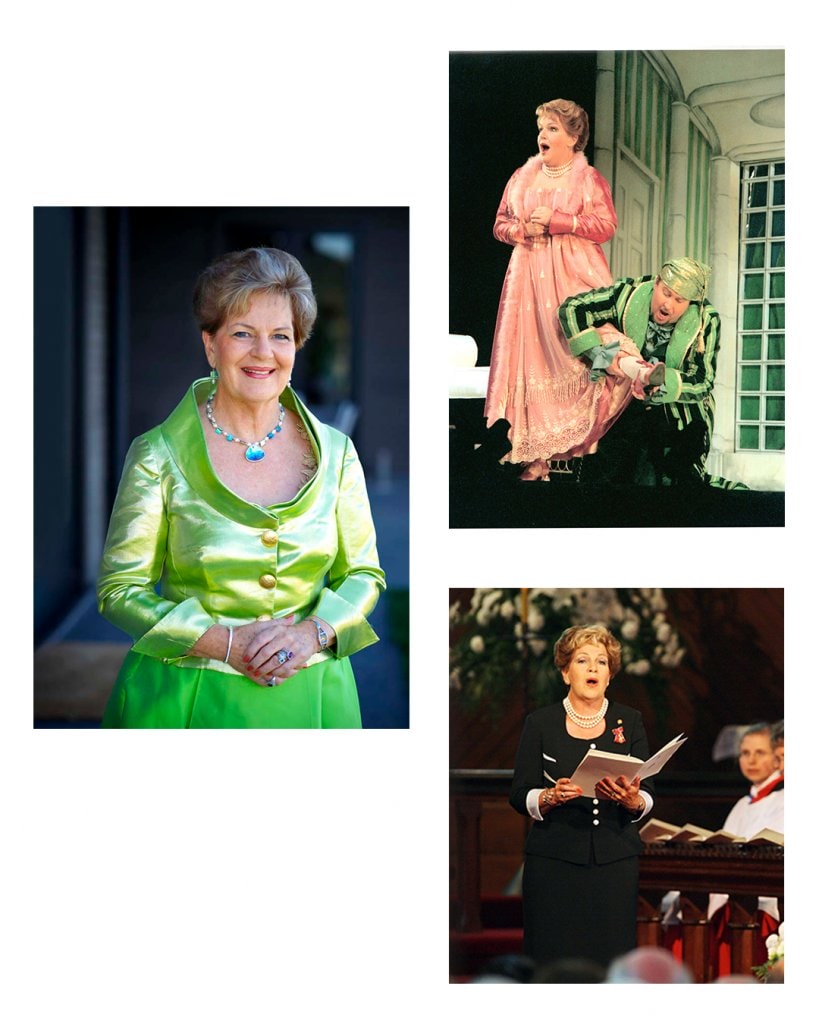

From international opera houses to universities and her own charitable foundation, Dame Malvina Major has spent decades using her voice for good. Now officially six years into retirement, the celebrated singer has some unfinished business to attend to. Sue Hoffart reports.

If Dame Malvina Major’s neat-as-a-pin Hamilton home was a stage, it would suggest a celebrated performer comfortably settling into her later years. Props include flourishing flower beds, knitting needles, nice china and plenty of framed photos portraying family, as well as her glamorous starring roles in European operas.

In reality, astounding levels of activity happen behind the apparently tranquil scenes here.

While her professional singing career ended in 2015, the diminutive dame continues to use her voice to fundraise, advocate and teach – despite dealing with the aftermath of brain surgery and complications from a decades-old brush with polio. She is currently penning what promises to be a profoundly personal book that will address trauma suffered in England and never publicly discussed, as well as details surrounding the woman who stalked her for 20 years.

At the same time, she’s fighting for a new kind of music degree and celebrating the 30th birthday of a foundation established in her name, while continuing to nurture and mentor young singers. She holds honorary doctorates at four educational institutions, is national ambassador for the kōkako and remains patron to an assortment of organisations, including Victim Support.

The woman who mastered multiple languages and juggled farming and motherhood with an international career is not good at everything after all – she’s obviously terrible at retirement.

Oh, there is no doubt the star of the show is a genuinely talented gardener and magnificent knitter, with a pile of fine white garments ready for the next great-grandchild. But the homecraft is also supposed to keep her out of trouble.

“I can’t sit down and do nothing,” Malvina admits, laughing. “That’s why I knit, so I sit down. I’ve had such a lecture about it.”

Medics and her family have been on at her for years to take on less. Only yesterday, she says, a specialist wagged his finger and told her to slow down.

“He said, ‘I have not had in my care a woman of 78 who does as much as you.’”

It’s been four years since that same specialist, a neurosurgeon, found an aneurysm lodged in an awkward corner of her brain. The nodule was a tricky shape and he warned Malvina that the resulting surgery could leave her wheelchair-bound, with epilepsy or worse.

“The only thing I’ve had is a bit of shaky hand,” she says, shrugging and waving the appendage to prove it operates perfectly well.

However, there is no brushing off a more recent diagnosis of post-polio syndrome (PPS), which explains the exhaustion that frequently sweeps over her in the afternoons. Naturally, the septuagenarian combats this by rising early and ticking off as many chores as possible in the mornings.

Malvina was 31, a mother to three children and a household name in New Zealand, when she was hospitalised for 10 days with “polio flu”, which temporarily paralysed her neck and part of her face. She eventually recovered – the treatment largely involved applying hot packs to affected muscles – before going on to embrace the second half of her international operatic career.

One of her seven siblings, older brother Gordon, contracted full-blown poliomyelitis as a child and Malvina has spoken alongside him to fellow PPS sufferers. She is keeping an eye on a government submission seeking help for the thousands of fellow Kiwis who live with the syndrome.

Audiences first heard her voice at age two, when the Hamilton-born preschooler insisted on joining her musical older siblings on stage. The family performed country music and yodelled in shearing sheds and halls while she was growing up, and Malvina also learnt highland and tap dancing. At primary school, the athletic, competitive farm girl could outrun every other girl her age in the district. Her secondary education at Hamilton Technical College was full of cooking, sewing and so much extracurricular music – piano lessons, theory and singing lessons – that she failed her school exams by four marks (though she did pass School Certificate the following year). Money was tight in the Major household, and it was resident boarder Dick Hunt who paid for piano lessons and bought Malvina her first piano accordion.

PHOTO SUPPLIED

Others had certain ideas about what the school prefect should do with her life. The college principal was sure she should become a home economics teacher, while her father was keen to see her sing on Broadway. But it was her Presbyterian mother Eva who prevailed, ignoring her daughter’s preference for show tunes and insisting Malvina take classical singing lessons with the Catholic nuns in nearby Ngāruawāhia each Saturday. Eva wanted her seventh child to sing opera, and Malvina came to love both the music and her kindly tutors.

The arrangement came to a sudden halt when she was preparing for a competition at age 17. The piano accompanist stopped her halfway through a rehearsal, declaring his horror that she was singing an Italian opera in English. He insisted she must have proper training with a renowned Auckland nun.

“There was a big hoo-ha, a big upset, and I was carted off to Sister Mary Leo.”

After four years of professional tutelage, the Waikato prodigy had taken top honours at every contest of note. It was obvious – much to her mother’s delight – that this voice was too big for Broadway. In 1963, the young performer won the prestigious national Mobil Song Quest, and in 1964 she won the Melbourne Sun Aria in Australia.

That same year, Malvina married 21-year-old Taranaki farmer Winston Fleming, with fellow soprano Kiri Te Kanawa as chief bridesmaid. Eva Major refused to attend the wedding due to the groom’s Catholic faith and her fear that the marriage was potentially detrimental to her daughter’s budding career.

In early 1965, the newlyweds headed to the United Kingdom, where Malvina took up a two-year London Opera Centre scholarship to hone her craft, learning German and Italian along the way. She’s since picked up some French and Russian.

The London sojourn was not easy. During the summer break that year, she gave birth to baby Andrew and affordable accommodation proved tough to find with a newborn. Then, when she returned to her studies a few months after the birth – an elderly couple cared for Andrew while Winston worked for New Zealand Dairies in the city – Malvina found her scholarship prize money payments had been severed.

“They said I was not serious about my career, I should have been at home with my child. It was horrific,” she recalls. “We were poor, I had this little baby. We didn’t have any support. I had no one to turn to. We bought seven meals a week. Chicken and turkey was the cheapest, we lived on them. And Winston’s brother sent us a food parcel of half a sheep for Christmas. We didn’t have a freezer.”

The young mother fought back, threatening to “tell every newspaper in the world” that she had been robbed of a prize fairly earned. Payments were eventually reinstated, though her training was cut short when she won the role that would launch her international career: Rosina in The Barber of Seville at The Salzburg Festival.

For five years, she sang her way to acclaim around Europe before giving it all away at 27, to follow her husband home to Taranaki. Daughters Alethea and Lorraine arrived in quick succession, the “major silver lining” to her stalled international ambitions.

“I left thinking it didn’t matter where I sang, as long as I sang,” she says.

And sing she did. For more than a decade, the diva was in high demand on stages around New Zealand: in city opera houses, at concerts, alongside the symphony orchestra. Sometimes the girls would travel with their mother when she performed, sometimes they stayed on the farm with their father.

“I was kept busy and I learnt a lot of roles, with smaller companies, that I would later do in Europe. And I learnt them in the proper languages. In a way, it was a good thing. The other good thing was my voice was not overused, which it could’ve been if I’d stayed in Europe.”

Her daughters were in their teens when the world came knocking, in the form of an insistent German conductor who visited New Zealand and asked after her.

“They said I was up country in my gumboots. He said, ‘Would you tell her I want her to come back to Europe and audition?’ My husband was supportive by then. I think Winston was a perfectionist and he liked to see his family and his children doing their absolute very best in whatever they did. That included me, so he suggested I go.”

Within two years, Malvina had a contract with Brussels Opera Company and the role of Arminda in La Finta Giardiniera. This second, longer act in her career would take her to South America, the Middle East, Japan and Russia. She took to the stage at London’s Covent Garden and sang alongside the Mormon Tabernacle Choir in Utah, performing for royalty and in New Zealand embassies throughout Europe.

However, there have been other pauses, most notably following Winston’s sudden heart attack in 1990. Her husband’s death rocked Malvina so much, she temporarily lost her voice.

After that there have been various sideline careers, as a professor of voice at the University of Canterbury and as a senior fellow at the University of Waikato, where she holds masterclasses for music students while helping to develop a dedicated opera programme – and fundraise for the required building – at the institution. Meanwhile, she continues to battle for a tertiary music programme better suited to singers.

“In New Zealand, music degrees are geared for instrumentalists. I’ve been fighting the university system since the ’90s and the University of Waikato is finally listening,” she says.

In New Zealand, music degrees are geared for instrumentalists. I’ve been fighting the university system since the ’90s

“We’re still turning out good singers. In England they ask, ‘Where do these New Zealanders come from?’ Sister Mary started the ball rolling, but the standard of teaching has just gone up as people came back from overseas to teach. Our training’s got better and better. But I still think we need a conservatorium of music totally dedicated to the art of opera.”

This ongoing drive to educate and help lies behind the Dame Malvina Major Foundation, which has been providing financial assistance, performance opportunities and professional guidance to young performing artists for 30 years.

PHOTO BY JAMIE WRIGHT

“When New Plymouth Rotary started the foundation in 1991, I wanted to help everybody. There was no support and New Zealand was a heck of a long way. There were no cellphones or computers or Zoom or Skype, and air travel was hugely expensive.”

While connectivity may have improved, she believes little else has changed since the hope, hardship and sense of isolation she experienced while launching her career overseas.

“You might have a scholarship to study, but sometimes you’ve got to get another job to put food on the table. You can’t study and work in a bar, you just get exhausted. And if you’re on your own, there’s nobody to support you. During Covid, there were a lot of emergencies because people lost their jobs.”

The foundation provides grants and scholarships, mentoring, tutoring and professional connections, and it embraces everyone from singers to conductors and ballet dancers, as well as operatic set designers and producers.

“It’s also about mental health and wellbeing. We try to help where we can, and make sure there are people you can talk to.”

This year, the dame’s official diary includes fundraising and celebratory events in five centres around Aotearoa to mark the foundation’s anniversary. In between, there are all the small kindnesses she show young artists: offering guidance on their repertoire before an audition, connecting them with teachers, supplying encouragement and no-nonsense advice.

She is also thinking about succession planning, too. Eldest grandson Thomas Fleming is already a foundation trustee but she is hoping to bring several other family members into the fold, too.

More time with her beloved family, more gardening and knitting are on the cards. This may also be the year she finally ticks off the major item on her to-do list: “do less”.