For 73 years, Prince Philip was the Queen’s great love and steadfast support through good times and bad. William Langley remembers the devoted duke’s lifetime of service.

Their lives had been intertwined for more than 80 years, through love, war and, above all, duty. Even the most extraordinary marriage of our times had to reach an end, and when it did, Prince Philip and the Queen were still side by side.

The 94-year-old sovereign personally oversaw her husband’s last days, assuring his comfort, rejecting suggestions that he might be taken back into hospital, and she was at his bedside when he died, as he had wanted, peacefully, in his private apartment at Windsor Castle.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

The story of Philip and Elizabeth was a great sweep of history, a great success, but also a great romance – one that began when they were teenagers, before World War II, and continued through decades of adventure, exhilaration and sometimes crisis, until the duke’s death on April 9, at the age of 99.

The Queen’s own tribute, delivered on the couple’s golden wedding anniversary in 1997, was hard to improve upon: “He is someone who doesn’t take easily to compliments,” she said, “but he has, quite simply, been my strength and stay all these years, and I and his whole family, and this and many other countries, owe him a greater debt than he would ever claim or we shall ever know.”

Although Philip’s health had been in gradual decline, he and the Queen were able to spend more time together in recent months. After his retirement from public duties in 2017, the duke lived mostly in a cottage on the Sandringham estate, while the Queen carried on in London. But the pandemic saw them both return to Windsor, and royal sources say the couple delighted in being back together.

Famously averse to illness, Philip was unsentimental about the prospect of death. Some years ago, his friend and biographer, Gyles Brandreth asked him if he would like to reach 100.

“Good God, no,” spluttered the duke. “I can’t imagine anything worse.” Already, he told Gyles, he had reached the point where “bits are dropping off”, and had no intention of sticking around longer than necessary. “Not me, no thanks,” he huffed.

In this, as in most things, Philip got his way. His death brought to a close a truly remarkable life. He was the ultimate consort, the reassuring, ramrod- straight presence always two steps behind the Queen. Yet at the end of their long, devoted life together, he remained much as he was at the start of it – a faintly mysterious and misunderstood figure, who almost no one could claim to know well.

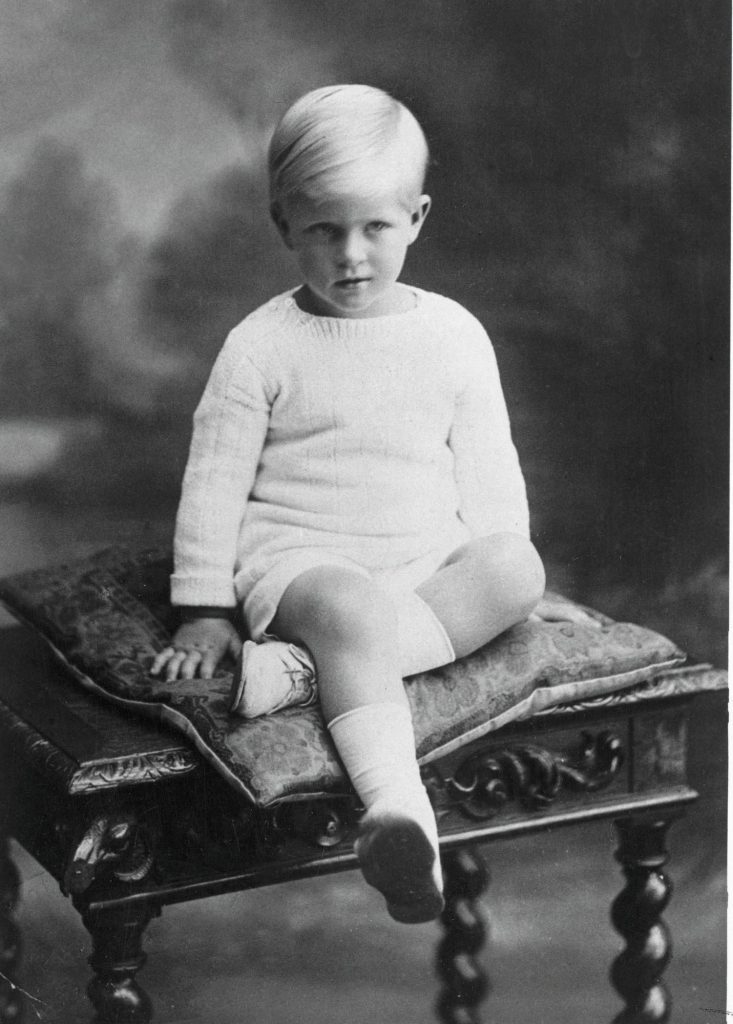

It wasn’t surprising. Philip had arrived in Britain as one more displaced aristocrat in an era which followed the collapse of many of Europe’s great royal houses. His parents, Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark and Princess Alice of Battenberg, had seen the monarchies of Germany, Austria and Russia toppled, and in 1922 were themselves driven into exile by political turmoil. A year earlier, Philip – their only son – had been born on the kitchen table of their seaside villa on the island of Corfu.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

“He is a splendid, healthy, beautiful child,” Alice wrote to her family at the time. “I am now enjoying the fresh air on the terrace.”

The enjoyment was not to last. Pending his banishment from Greece, Andrew was placed under house arrest, and Alice, fearing for the family’s future, begged her British relatives for help. Buckingham Palace put in a word to the government, and a Royal Navy warship, the HMS Calypso, was sent to rescue them. Baby Philip was carried aboard in an orange crate, with the family’s meagre possessions.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

His older sister, Sophie (later the Princess of Hesse) recalled that her last memory of the family home was the smell of smoke billowing from every fireplace as her parents burned all their paperwork – letters, court papers, financial documents – to leave nothing behind that could incriminate them.

The family’s fond hopes of being allowed to settle in London were dashed by political complications, and they were effectively dumped in the small port of Brindisi at the bottom of Italy: “The most dreadful place I have ever been to,” wrote Sophie. The Italian government proved no more welcoming than the British, and the family made their way by bus and train first to Rome, then Paris, where they managed to beg temporary quarters from friends.

Although the British press would later give Philip the irreverent nickname of “Phil the Greek”, he delighted in pointing out that he had not a drop of Greek blood, his father being German

and Danish, his mother Russian and his relatives a bewildering mix of the greater and lesser European nobility. Where, then, was he actually from?

It was a question he never wanted to answer. Biographers portrayed him as a lost child, unable, even as an adult, to escape a legacy of rootlessness which left him with no sense of belonging. Writer Fiammetta Rocco remembers asking Philip what language his family had spoken at home.

The immediate retort was: “What do you mean ‘at home’?”

IMAGE VIA GETTY

In the early days of exile, “home” was a borrowed villa in the Paris suburb of Saint-Cloud, but Andrew and Alice were chronically short of money, without prospects and dependent on the goodwill of relatives. The strains showed in their marriage and, while Philip was still small, his mother suffered a mental breakdown. Always deeply religious, Alice took to proclaiming herself a saint and the bride of Christ, and in 1930 was committed to a psychiatric clinic

in Switzerland.

Andrew deserted the family shortly afterwards, drifting for some years around the fleshpots of the French Riviera with a string of mistresses, before settling in Monte Carlo, where he spent his years drinking and gambling until his death in 1944, aged 62.

Philip’s four older sisters departed to Germany to study or marry available noblemen, and the lone boy became the object of a tug-of-war between the scattered branches of his family. “No one really won, so he ended up being sort of shared around,” said Ingrid Seward, editor of Majesty magazine. “It must have been very strange for him.”

IMAGE VIA GETTY

Philip, though, never complained about his chaotic childhood, insisting he was happy, and

that – as children do – he accepted the abnormal as normal. Nor would he hear any criticism of his parents. “I have only heard him speak of them with sympathy, respect and affection,” wrote Gyles Brandreth. “Fine portraits of them hang in his study, and to this day he wears his father’s signet ring.”

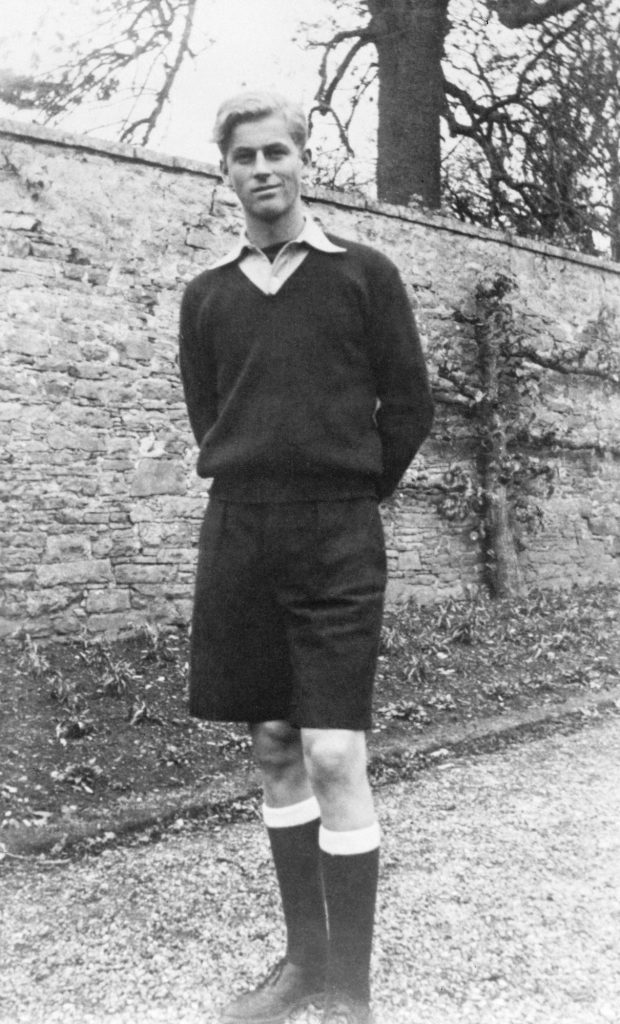

Philip spent two early years in England with his uncle, the Marquess of Milford Haven, before being snatched back at the age of 13 by the German branch of the family and sent to boarding school in the small, southern town of Salem. Here, beside the beautiful, wooded shores of the Bodensee lake, the boy from nowhere had a rare stroke of luck.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

The school’s headmaster, Kurt Hahn, an idealist who believed that testing and rigour brought out the best in boys, was arrested for attending an anti-Hitler demonstration. Being part-Jewish, he sensibly decided to flee Germany for Britain, where, a year later, he founded a new school, Gordonstoun, in northern Scotland. It was there that Philip – under a complicated family accord – arrived as a pupil in 1934.

Philip often spoke of Gordonstoun as the making of him. The regime was tough – boys had to rise from their unheated dormitories at 6.30 am, put on their gym kit, run 300 yards (274m) barefoot to the washrooms and shower in cold water. Meals were basic, discipline firm and visits from parents discouraged.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

“I would not have missed the experience for anything,” Philip later said. “The discomfort was far outweighed by the moments of intense happiness and excitement.”

Those five years at Gordonstoun left him with an ironclad self-reliance and the confidence that he could cope with anything. These were qualities he would soon need.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

Philip still knew almost no one in Britain, had largely lost touch with his family, lived on a meagre allowance – apparently funded from his father’s occasional roulette winnings – and, apart from dazzling good looks and an aristocratic name, had very little going for him. One person he did know was his uncle, Lord “Dickie” Mountbatten, a court favourite and dashing Royal Navy commander, who now took Philip under his wing.

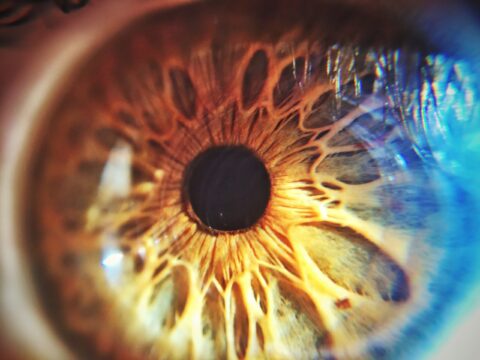

It was Dickie who advised Philip to join the Navy, and in late 1938, the 18-year-old prince enrolled as a recruit at the Royal Naval College. He impressed from the start, scoring high marks in virtually every subject, but it is for a different reason that his time at the college is best remembered. On July 22, 1939, a royal party paid a courtesy visit, and among the guests was 13-year-old Princess Elizabeth.

This is accepted as the couple’s first meeting, although Philip, with typical incorrigibility, always claimed to have no memory of it. Elizabeth was unlikely to forget, though, for the early pictures of Philip in uniform show an exotic creature with pale gold hair and penetrating blue eyes. She reportedly kept one on her bedside table, long before she and Philip became a couple.

According to his contemporaries, the young Philip was fully aware of his attractiveness to women. “He was very beautiful, amusing, full of life and energy, and he was a tease,” recalled his cousin, Princess Alexandra of Yugoslavia, after accompanying him on a trip to Venice. “Blondes, brunettes and redhead charmers, Philip gallantly squired them all.”

But the squiring ended with the outbreak of war. He saw active service in the Mediterranean, was mentioned in dispatches and, by 21, had risen to become one of the navy’s youngest lieutenants. The war, as one biographer put it, “finished the job that Gordonstoun had started”, and Philip emerged as tough and able as he was glamorous.

His ambitions now switched towards Elizabeth. On shore leave, he would roar up to London in his black MG convertible to visit her at Buckingham Palace or Windsor. Barely out of her teens, the future queen was a shy, obedient girl, brought up under the protective eye of her father, King George VI, who was far from convinced of Philip’s suitability.

IMAGE VIA GETT

Who was he, the King wanted to know. Philip may have had a decent war, but his background was murky, he lacked a proper name, wasn’t British, came from the Greek court – which was a byword for instability – and didn’t belong to the Church of England.

It wasn’t until 1946, following an invitation to Balmoral, that the relationship became a commitment. “I suppose one thing led to another,” the duke once shrugged with his trademark taciturnity. “It was sort of fixed up. That’s what really happened.”

It is unthinkable that they could have lived such a life as they had without truly loving each other

If this suggests something less than a man swept up in a raging storm of passion, the duke’s friends were keen to point out that he was deeply in love with Elizabeth and remained so for the rest of his life. “It is unthinkable that they could have lived such a life as they had without truly loving each other,” wrote biographer Philip Eade. While rumours of infidelities pursued the duke through the decades, nothing was ever proven, and not one of the many women into whose arms he supposedly strayed chose to kiss and tell.

“Philip is certainly a man who enjoys the company of attractive younger women,” observed his cousin Patrica Knatchbull, Countess of Mountbatten, “but I am quite sure – absolutely certain – that he has never been unfaithful to the Queen.”

IMAGE VIA GETTY

By “fixed up”, Philip didn’t mean the marriage was arranged. Far from it. Both of Elizabeth’s parents still had strong doubts – ones that would endurefor many years in the case of the Queen Mother.

It meant a deal was struck that would allow the couple to marry in exchange for Philip becoming a “proper” Englishman.

He took the name Mountbatten, was received into the established church, and the pair were married in Westminster Abbey on November 20, 1947, in a service broadcast to 200 million people around the world.

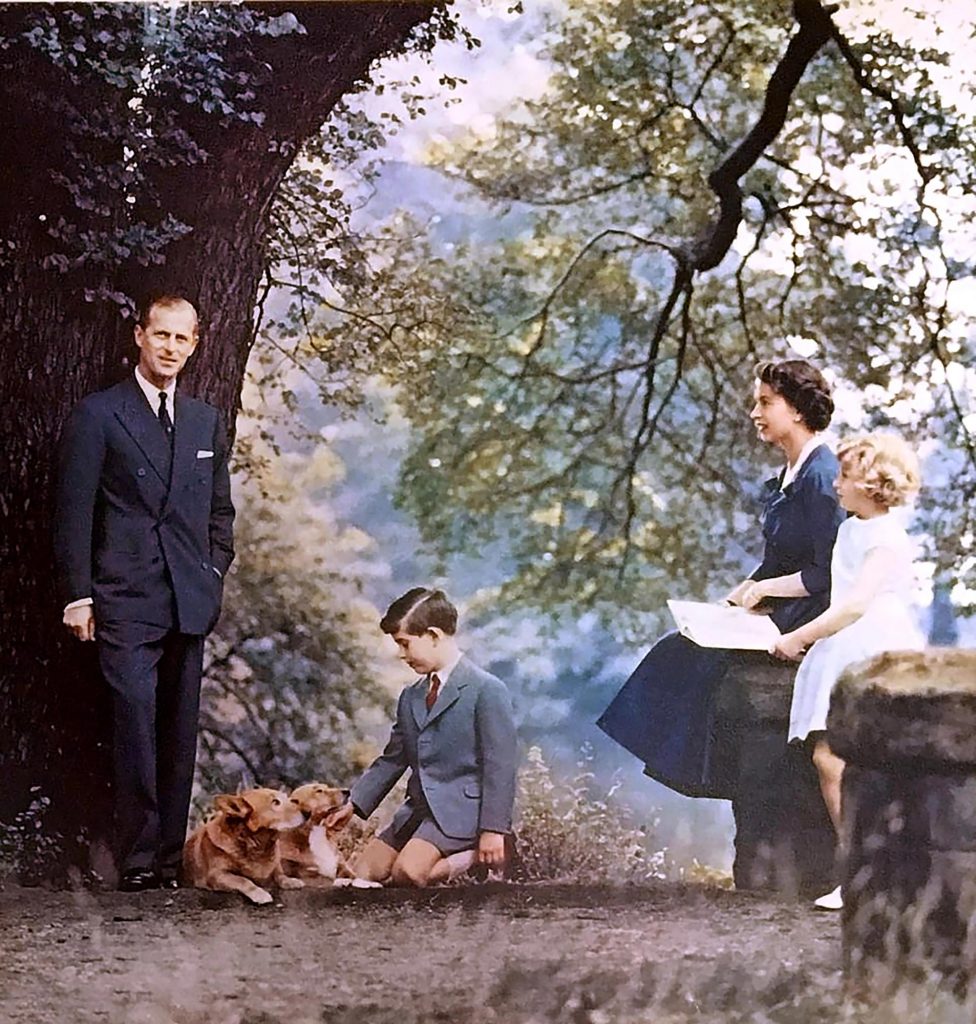

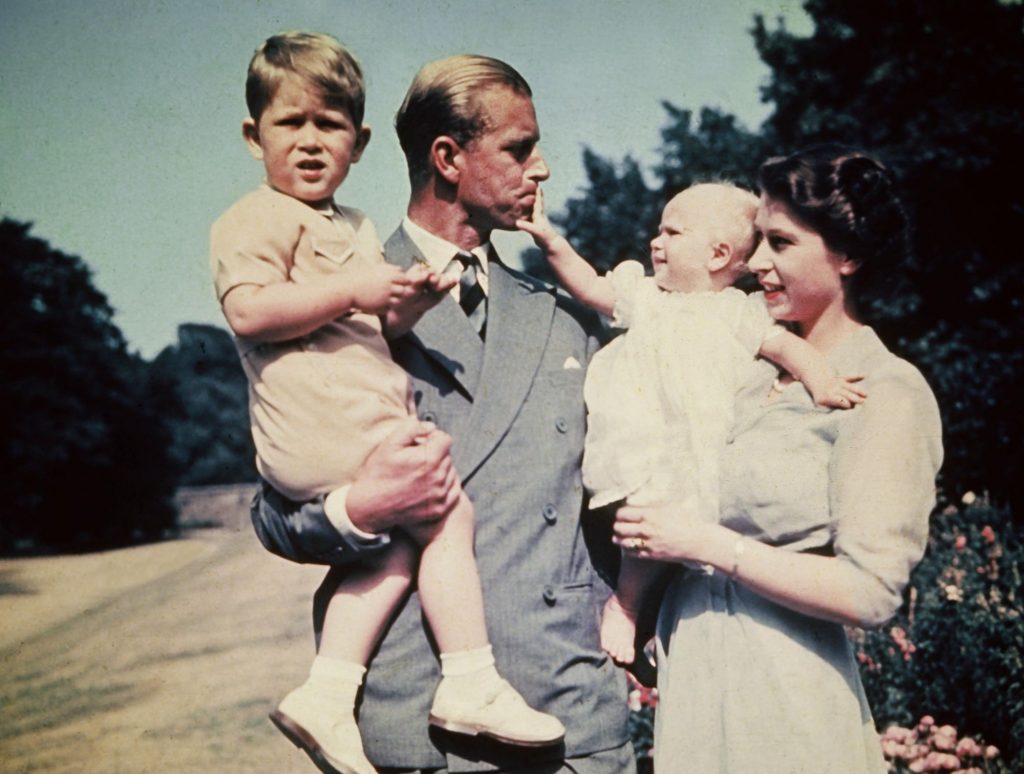

IMAGE VIA GETTY

At first, Philip’s life didn’t change much. He continued as a serving naval officer, and took the arrival of his first two children – Charles in 1948 and Anne in 1950 – in his stride. But in February 1952, while travelling with Elizabeth to Australia and New Zealand via Kenya, news arrived that George VI had died from coronary thrombosis, aged 56. In that instant, Philip’s entire destiny was reshaped. From being his own man with a career and prospects, he became a full-time royal consort whose life would be measured out in handshakes and how-do-you-dos.

Those who would later complain of Philip’s irascibility and “lack of an emotional middle”, as one senior courtier has put it, were almost certainly witnessing the consequences of a man of action forced into an essentially inactive role. He faced up to the inevitable with stoicism, but as he traipsed that precise two steps behind the Queen, smiling gamely and listening to the supine niceties of assembled worthies, it wasn’t hard to imagine his sense of opportunities lost.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

The first thing to go was his naval commission. Philip, like many men from dislocated childhoods, seems to have found a particular comfort in being part of a ship’s company. He never fully recovered from the loss of his command, saying bitterly in an interview years later, “It wasn’t my ambition to be the president of the Mint Advisory Committee, the president of the World Wildlife Fund. I was asked to do it. I’d much rather have stayed in the navy, frankly.”

For a while he despaired, falling ill with jaundice, a condition often associated with stress and depression. Once again, it was the Queen’s love and good sense that carried him through. They would be a partnership, she explained, and his role in it was indispensable. He must never feel like the lesser partner. The spotlight may be on her, but without him she could achieve nothing.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

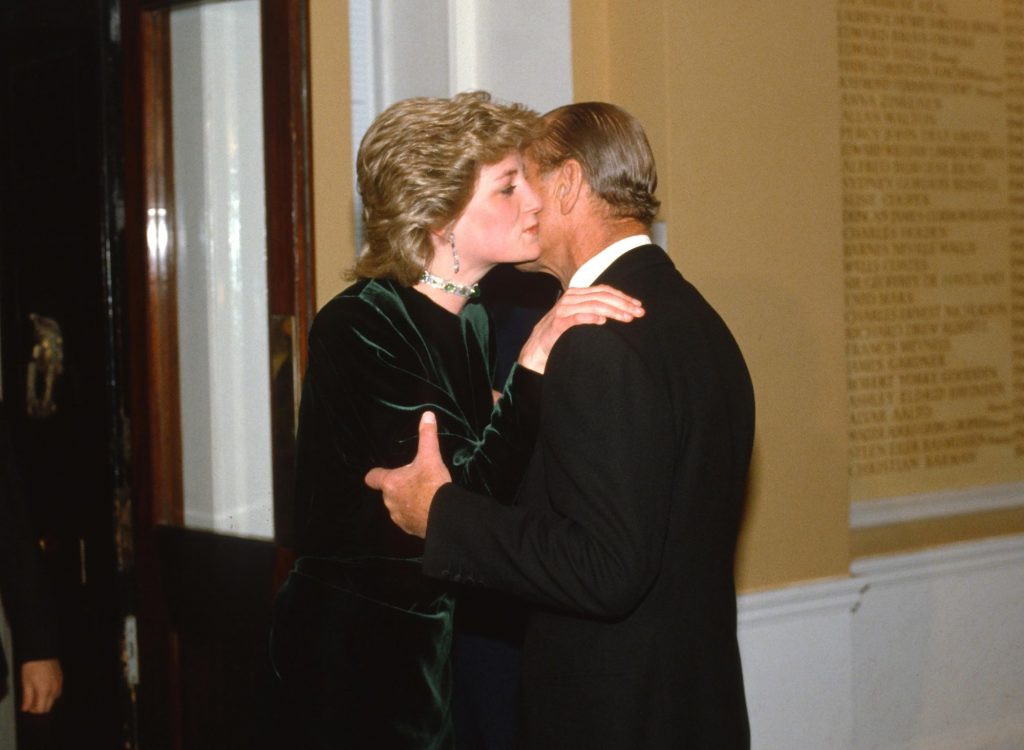

The gentler side of his nature was hard to spot. Philip made no secret of his disdain for the modern tendency towards self-pity and confessionals, and struggled to comprehend the inability of his own children to “stick with it” when their marriages ran into trouble. Yet, in the right circumstances, he could show great tenderness and understanding. When the marriage of Charles and Diana, Princess of Wales, ran into trouble, it was Philip who played moderator.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

A remarkable series of letters between him and Diana illustrated the depth of his concern. “Dear Pa,” wrote the princess in reply to one offer of help. “I was particularly touched by your most recent letter, which proved to me, if I did not already know it, that you really do care. You are very modest about your marriage guidance skills! This last letter of yours showed great understanding and tact, and I hope to be able to draw on your advice in the months ahead, whatever they may bring. With my fondest love, yours Diana.”

Charles remained largely incomprehensible to Philip, and although the tensions were managed as politely as possible, there was little warmth between them. The duke saw his son as a woolly-minded romantic, “precious, extravagant and lacking in dedication”, while Charles thought his father cold and domineering, and, in a series of interviews with the British broadcaster David Dimbleby, made clear that the unhappiness of his own childhood was largely down to his father’s relentless criticism.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

The Queen, at least, understood the sincerity of her husband’s reasoning. Elizabeth, indomitable as ever, must now carry on without her staunchest ally. Her workload, already discreetly reduced, will likely be scaled back further, but no one believes she will step down. The words she addressed to the Commonwealth on her 21st birthday still ring resoundingly true: “I declare before you all that my whole life whether it be long or short shall be devoted to your service.”

After the eight days of official mourning, the Queen is likely to spend another 30 days mourning

in private. Then, she will quietly return to her duties. “The Queen and duke were completely “ together on this,” says a courtier. “They had plenty of time to prepare for it.”

In later life, the duke would cheerfully admit that most people saw him as “a cantankerous old sod”, and his ability to say the wrong thing became almost legendary. The royal press corps revelled in what became known as Philip’s “gaffes”, yet none doubted that without his support, the Queen’s long and almost flawless reign would have been impossible. He was the cornerstone of her life.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

The deeper nature of their marriage remained a mystery. Almost everyone who knew them was struck by the difference in their characters. “They are not at all alike,” wrote Brandreth. “They have different interests, different attributes, yet they understand one another. Completely. And they are allies.”

They have different interests, different attributes, yet they understand one another. Completely. And they are allies

Displays of affection were not Philip and Elizabeth’s way. “I always wanted to see him put his arms around the Queen and show everyone how much he adored her,” said Mike Parker, Philip’s private secretary and closest friend. “I mentioned it to him a couple of times, but he just gave me a hell of a look.” The role of consort had become his life’s work.

Countless organisations and good causes benefitted from his time and energy, and for many years he monopolised the accolade of “hardest-working royal”, notching up hundreds of engagements every year.

The pace barely slackened until 2017, when, with little fanfare but a great wave of public gratitude, he announced his retirement. For the last years of his life, the duke lived quietly at Wood Farm, a spacious but simply furnished cottage on the Queen’s Sandringham estate in Norfolk. Well, as quietly as someone like Philip could manage. There was the time he piled his Land Rover into another car, triggering a national debate about the wisdom of allowing 97-year-olds behind a steering wheel. And the characteristically iffy joke he made in 1988 about wanting to be reincarnated as a virus “to contribute something to solving overpopulation” has resurfaced online since the Covid-19 lockdown.

IMAGE VIA GETTY

Mostly though, he spent his time painting, reading and having old friends to stay. Retirement forced a poignant separation from the Queen, who, as ever putting duty first, remained mostly at Windsor or Buckingham Palace. No one doubted how much she missed him, not least because,

as biographer Hugo Vickers said, “He is not only her most trusted advisor, but the only person

who treats her as another human being.”

IMAGE VIA GETTY

Even more than most of us, the duke hated being ill. It was, to this indomitable old seadog,

a sign of frailty, and although the hospital visits became more frequent, he would make a point of marching out, chin up, with a look of something between impatience and indignation in his eyes.

“Are you feeling better, sir?” a reporter would shout.

“Well, I wouldn’t be going home if I wasn’t,” barked Philip.

And so he was to the end. Exasperating, endearing and still misunderstood.