The Times/News Licensing

She’s never been drunk, gives away her earnings and can’t imagine a normal future for herself. In June 22 Caitlin Moran met the remarkable climate change activist, still only 19.

Man, it’s hard, getting ready to meet Greta Thunberg. She’s like an Instant Ethics Audit Mirror on legs – ten minutes before I meet her, I have to google to see if my (second-hand) top was created in a sweatshop, chuck my half-finished can of hangover-curing Diet Coke in a bin, and fret if it’s obvious that my Doc Marten boots are the leather ones rather than the far more acceptable vegan options. Meeting Greta Thunberg with World-Destroying Accessories is like when your kids smell fags on you: you can’t bear that they will think less of you. You want to be a better person than, sadly, you really are.

I do my first interview with Thunberg – currently, in the absence of Iron Man, the only viable candidate fielded by humanity to Save The Entire World – at Glastonbury Festival in June, because we both happen to be there. She to give a landmark speech to 250,000 people about instigating organised public intervention on global warming. Me to get a bit pissed up on cider and see Sugababes.

This is the only point in our schedules we can manage it – she lives in Stockholm and won’t give interviews to anyone who’s flown out to see her. It’s absolutely fair that her principles mean you can only travel to see her if you’ve gone by rail or electric car. Personally, I would happily walk to see her as I think she is astonishing – by some measure one of the most galvanising figures of the past 100 years. But it is actually easier to make my way on foot through the warren of backstage dressing rooms and tents – past loitering Kate Mosses and Bruce Springsteens – and find her half an hour before her unannounced special appearance on the Pyramid stage, which later makes world headlines.

What is she like? This extraordinary figure who, since the age of 15, has had the status of a stateswoman and prompted the biggest climate change protests in history: an estimated 4 million people across the globe on September 20, 2019. I remember that day – my teenage girls went to the strike too. London was brought to a standstill, called out by a girl people had never met, thousands of miles away. Courage calls to courage everywhere. Children stood in front of buses on Waterloo Bridge and chanted, “No future! No change! They want things to stay the same!”

My kids came home high and giddy. They had never experienced anything like it. “It was all people like us,” they said. “Everyone was our age. We all held hands and laid down in the road. A policeman came over and whispered ‘We’re on your side, mate. Good on you.’ ”

The whole world knows her name, including Donald Trump, who as president seemed personally enraged by her. When Thunberg was named Time’s Person of the Year after giving an impassioned, tearful speech to the UN General Assembly – “I shouldn’t be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you! You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words” – the most powerful climate-denier in the world tweeted: “She seems like a very happy young girl looking forward to a bright and wonderful future. So nice to see!”

She seems like a very happy young girl looking forward to a bright and wonderful future. So nice to see! https://t.co/1tQG6QcVKO

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 24, 2019

Two years later, when Trump was finally booted out of the White House, Thunberg calmly tweeted, “He seems like a very happy old man, looking forward to a bright and wonderful future. So nice to see!” Aside from everything else Thunberg has achieved, most comedians will admit she also delivered one of the all-time great comedy callbacks.

He seems like a very happy old man looking forward to a bright and wonderful future. So nice to see! pic.twitter.com/G8gObLhsz9

— Greta Thunberg (@GretaThunberg) January 20, 2021

I sit in her empty dressing room waiting for her. What is she going to be like, this droll person who is both incredibly powerful but also still barely out of childhood? This student who addresses governments, and Davos, in her sneakers? Someone who’s had so many death threats after her brilliant trolling of an old man with actual nuclear warheads that her family had to put security outside her home, but is spending this weekend camping, anonymously, in a tent among 250,000 other revellers?

When she enters the room –very small, barely 5ft, in a T-shirt, jogging bottoms and old vegan trainers, hair unbrushed – she has a very still, Quaker-like air. Everyone else is fluttering around making small talk, but Thunberg clearly doesn’t talk unless she needs to. It’s not a saturnine silence – like Eamonn Holmes on This Morning when he was peeved about a cookery item that went wrong. Instead, it’s an incredible stillness and self-possession.

I’ve seen many, many people as they prepare to go on stage – pacing around, riding adrenaline, hectically joking – or else going so ferociously “within” that it feels inappropriate to be around them. By way of contrast, Thunberg has the kind of quiet power I have never seen in anyone else, particularly someone so young and alone. She just… sits and eats an apple, watching everyone else around her.

“It’s time,” the stage manager announces.

As Thunberg starts her walk towards the stage, a crowd of people – her friends; her book publishers; Mary McCartney, photographing her; Glastonbury organisers – follow in her wake. But she walks ahead alone, holding the four A4 pages of her speech, with the kind of authority actors try to embody when playing Elizabeth I or Joan of Arc. Visually, she’s a tiny, scruffy kid. But she walks like the person who can convene a Galactic Republic. She’s like a cross between Princess Leia – another teenage girl with a big mission – and the Dalai Lama. I don’t know any other way to describe it.

As she mounts the steps – the faces of the waiting 250,000 people a pinkish blur in the background – I flash through her life so far: her undiagnosed autism; the eating disorder that led to her losing 20lb; the first school strike – just her with her placard on the steps of the Swedish parliament; the growing crowd of people who joined her; the global school strike in March 2019 that brought 1.4 million children out onto the street; her addresses to the UN and Davos. The three nominations for the Nobel peace prize. The millions of online trolls, bots and abusers – Talk Radio host Kevin O’Sullivan calling her a “Swedish doom goblin”; calls for someone to “grab her pigtails and [Miss Trunchbull] her over the fence”; Jeremy Clarkson calling her “a little bucket of ego” who needs “a smacked bottom”; Helen Dale in

The Spectator looking forward to seeing Thunberg “have a meltdown on national telly”. The president of the United States getting the audience at one of his rallies to boo the mention of her name – when she was still just 17. What a ride the past few years have been.

I stand at the side of the stage as Thunberg walks on. Her mike fails; she’s given another. The wind blows the sheets of her speech around; she continues, unperturbed. Although this is a huge crowd of drunk people at a festival, she gives her speech to total silent concentration and attention. And, several times, to spontaneous, furious applause.

“This is not the new normal,” she says to a roar. “It has not only become socially acceptable for our leaders to lie, it is more or less what we expect them to do. You and I have been given the historic responsibility to set things right. Together, we can do the seemingly impossible. But make no mistake, no one else is going to do this for us. This is up to us here and now. You and me. We are approaching the precipice… Do not let them drag us another inch closer to the edge. Right now is where we stand our ground.”

Later that night the speech makes news headlines around the world. Thunberg’s face is, once again, on the cover of newspapers and magazines. She trends on Twitter.

Three weeks later, Europe is hit by an unprecedented heatwave – a glacier collapses in the Italian Alps, the UK records its highest temperature, rivers dry up, Australia suffers widespread flooding and Syria announces an impending famine because of drought. If Thunberg is a “doom goblin”, then I don’t know what we call the actual news. Or maybe we only insult the teenage girls who give up their futures to report the facts.

So this is the first Greta Thunberg I meet. The world leader. The second Greta Thunberg – it’s pronounced “Gre-AATa Toonberg” – I meet the following day. We’re in a tiny caravan in a hidden part of the festival grounds – organiser Emily Eavis has let us use it so “Greta doesn’t get any hassle” – but, to be honest, we don’t need it. That quietly powerful centre of attention who yesterday walked like a queen is gone. Indeed, on our walk to the caravan I bump into two friends who ask me, surprised, “Have you already done Greta?” – only for me to introduce them to the silent and almost invisible girl standing beside me. Today, Thunberg has turned off whomever she needed to be yesterday to walk onto that stage. Today, she’s a home-schooled teenage girl with Asperger’s who used to have an eating disorder and selective mutism and who’s just written her first book. She’s just a girl. Princess Leia off duty. We sit, drinking water, and I start by asking her what I’d ask any teenager:

“So, how are you finding Glastonbury? Is this your first festival?”

“Yes,” she says.

It’s not only her first festival but her first gig – she’s a lockdown teenager. All those years every other generation spent going out she spent at home, waiting for the virus to pass. She and her friends have camped “up on the hill”. Greta went to bed earlier than everyone else. “The ground was moving because of all the noise.” She seems slightly bemused by the whole event. Later, when we go walking around, she confides, “All these cool people keep coming up to me saying, ‘We love you – hello, Greta!’ And when they have gone, people tell me they are actually from a very famous band. But I’m afraid I don’t know them.” She laughs. She laughs a lot. Her replies might be quite short, but she’s very open and ready to be amused by anything. She might be thoughtful and precise in her replies, but also utterly spontaneous. All famous people have their “bits” – the pat answers they give to common questions. Thunberg, uniquely, has no “bits”. Everything she says is new, honest, raw and open.

I try to get a sense of her social life. Has she ever been drunk? Has she been tempted by Glastonbury’s hedonism?

“I would never go out drinking,” she replies. “I would never do anything… stupid, and I don’t know if that’s because I’m that kind of person or if it is because I don’t want to be ‘seen’. I guess it could be both.”

“So you have never got drunk, then?”

“No.”

“Is that because you’re aware there are a lot of people who would be like, ‘I want to be the first person to get Greta Thunberg drunk.’ ”

“Yes!” She laughs.

“And do you have the same worry about talking to a girl or boy you fancy? That everyone would be like, ‘Oh, look who Greta Thunberg is chatting up!’ ”

“Yeah. If I come up to them, you’re more vulnerable. So you have people looking up to you, but you’re also much more vulnerable.”

“So you have power – and also, oddly, no power.”

“Yes.”

“Have you ever spoken to any other girl who became famous when they were teenagers? Lily Allen, say, or Billie Eilish? Who know what it’s like to have people watching you, and commenting on you, even when you’re still growing up?”

“Not really, no. It’s difficult because, in one way, I feel like I’m just an activist – we know how to organise a strike, how to talk to politicians. But on the other hand, my position is very different [from other activists]. There are very few who have the experience of being a grassroots campaigner and also being followed by the paparazzi. Someone recently told me I am an influencer, but I don’t like that.”

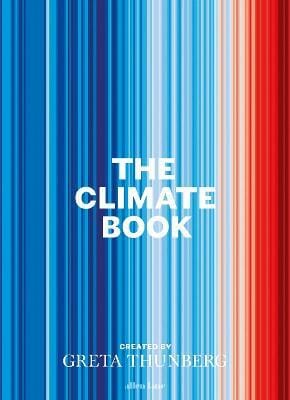

This binary – of being one of the most famous people in the world; a celebrity, but without any of the privileges, protections or rewards of every other celebrity – is one we’ll return to. For now, I want to ask her more about culture and music. For while lockdown kept her away from festivals, gigs and fun, it gave her the time to write her first proper book, The Climate Book, which is what we’re here today to talk about.

“So, you’re an author.”

“I don’t consider myself an author. It sounds weird.”

“Well, you are. Congratulations on a new career. How do you write? What’s your routine?

When do you write? Some people feel cleverer in the morning, others in the evening.”

“I would say I am ‘cleverer’ in the morning.” She laughs, humouring my question. “But I don’t usually have the time because I need to go to school. I wrote most in winter, after school, when I had the time, which was not optimal, because I’m not an evening person. But I had to do it.”

I ask her if she listens to music while she writes and she shows me her playlist:

Queen’s Somebody to Love; KC and the Sunshine Band;Billie Jean;Blame It on the Boogie

;Should I Stay or Should I Go. Upbeat party bangers. The last song, however, is Bonnie Tyler’s Holding Out for a Hero and, I admit, seeing it makes me feel a little tearful: Bonnie’s just singing about wanting to get laid by a streetwise Hercules. For the teenage girl listening to it during winter lockdown in Sweden, coping with death threats, writing a book about trying to save the world, it feels a bit more… meaningful.

The Climate Book is intended to be the manual for understanding what is happening to the world, why, and how to change it. Thunberg has convened every available expert – Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the World Health Organisation; Saleemul Huq, director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development; Rob Jackson, chairman of the Global Carbon Project; Lucas Chancel, co-director of the World Inequality Lab; Silpa Kaza from the World Bank; economist Thomas Piketty – to write on their specialist subject. Almost everyone listed is a marine biologist, emeritus professor, research director, historian, epidemiologist or head of a university or global organisation.

The Climate Book has pictures of husky sledges attempting to cross ice packs 3in deep in meltwater; sea-battered plastic shampoo bottles that have crossed the Pacific and will be with us for another 1,000 years; and a collection of the most alarming graphs ever gathered in one place. But although it is a big book,it is ultimately a very hopeful book, because Thunberg’s 18 linking essays frame things in a unique way. One thing she says I found particularly resonant: “Some people believe that if they were to join the climate movement now, they would be among the last. But that is very far from true. In fact, if you do decide to take action now, you would still be a pioneer.”

“This!” Thunberg says. “Yes! People think they can’t contribute anything; that they don’t know what to do. But if you fully understand the climate emergency, you will more or less know what to do.”

The book ends with two very punchy pages: “What we can do as a society” and “What you can do as an individual”. “Be a nuisance. Be disruptive. Democracy is the most important tool we have – defend it. Vote. Avoid culture wars. Skip past phrases like ‘taking small steps in the right directions’. Plant trees. Invest in wind and solar power: the miracle has already happened. These are global game-changers.”

“It was important that it was collaborative,” Thunberg says. “Because from the beginning, all I have ever said was, ‘Listen to the scientists. Listen to those who are affected.’ I’m not an expert. I don’t have the mandate to speak about these things; [the only] mandate I have is to express my own opinions.”

The book is being published in 15 countries. More will follow. I would hope it is the kind of book everyone feels they should buy, read and act on: if you’ve tried to recycle a coffee pod, bought an electric car or started using a reusable water bottle, this book knows the combination of fear, hope and duty that made you do it and has a million more suggestions. It should be a bookcase staple, like Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time or Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens. Unlike Hawking or Harari, however, if Thunberg’s definitive book on climate change does become a global bestseller, it will earn her no money.

“The proceeds that I will make will go to charity,” she says. “It would be nice to have money, but by donating… For example, if I donate it to rewilding or nature conservation, I can start a debate on that. If I donate to refugees, you can talk about why – and then you can explain.”

“So you are earning no money from this book at all?”

“If I translate the book from English into Swedish [Thunberg writes in English], then I can get some kind of reimbursement for the time I spend doing that, because I’m not doing it for promotion. It’s like a… specific job.”

For the only time during our conversation, Thunberg seems awkward and embarrassed. The tone is apologetic. She clearly feels conflicted about even earning a small fee for her translation work. I hate this for her. Even girls who are saving the world need an income.

“Do you have any dreams of the future? Where you’d like to live and who with, and what you’d like to do, aside from saving the world?”

“Sometimes I find myself thinking, ‘What do I do with my life?’ And it ends up with, ‘I can’t predict anything. Let’s vibe!’ ”

She laughs, a little sadly.

“I think we are more or less morally obliged to be activists, but you can’t really earn a living on that.” She laughs again. “So what income do you have?”

“CSN.”

“What’s that?”

“Like, the money you get every month for studying.”

“So, like a student grant. That’s it ?”

“Yeah. Right now. But it’s not very sustainable. When it comes to artists or influencers, they can earn money without people being mad at them, but I can’t.”

I’m afraid the horrified mother in me asks, “But the thing about money is, it keeps you safe. It’s important for women. What if you need to get a taxi home late at night?”

“I always walk. Maybe I should be more cautious.”

“Have you never taken a taxi?”

“I guess if I needed to; it’s just I haven’t felt the need. Probably I should be more careful. People tell me I should.”

“What about security? You’re one of the most famous people in the world. You have constant rape and death threats on social media.”

“There was one period I had security guards, but it only lasted a few days.”

This was after Trump’s attack on her. “There were people and stuff outside my house, so it was justified. They were… filming.”

This is why Thunberg now lives in a friend’s apartment. Addresses are public in Sweden – if Thunberg were registered as the official tenant of an apartment or house, everyone would know where it was. Even so, “Sometimes people knock on our door and try to get in, which is not very… pleasant.”

Asked if she’s scared for herself, Thunberg replies, “It’s just, if people I love get mentally or physically harmed by it…” before trailing off.

Now fully alarmed by her life, I ask if she has “people”: a team to help her with her schedule, organise her affairs, support her in the way literally any other global figure is supported. No. “I book my own trains and where I stay… I always bring my own food. For example, I could just eat bread, plain bread, every day.”

The awful thing is, this is how society needs Greta Thunberg to be. She’s correct: what “job” could she take, what money could she earn, without people calling her a “hypocrite” or “sellout”? The template we have for young women who want to save the world is that they

Need to be vulnerable: that is their crucial strength. Sleeping on friends’ sofas, eating plain bread, booking her own standard-class tickets on a train to go and deliver a globally reported speech to 250,000 people, rucksack on her back. We understand a young woman if she operates essentially in the realm of a martyr: basically defenceless and good and utterly pure of any money, protection or power – other than the power of her own… defenceless goodness.

This isn’t down to bad parenting from Thunberg’s family – “I have such a good, solid family.” It was her father’s yellow raincoat she wore in those first iconic school strike photos. At the time Thunberg was starving herself, in the grips of an eating disorder, and electively mute: finding a cause she believed in saved her. Besides, anyone who thinks they can tell a 15-year-old girl what to do has never met a 15-year-old girl. No, this is down to whom we listen to and why. Thunberg’s innate understanding of how she “must” be, if she is still to have a global platform, is entirely correct. Even as things are, there are still insane conspiracy theories about her validity to speak. She lists them, laughing: “I am a Russian spy; I am being funded by rich Americans; I don’t really believe in climate change.”

And although it has given her a global platform, my worry is: if being a young, global figurehead for the most important conversation exhausts our young, global figureheads – if it means they can never earn money, be secure, plan a future, consider having a family or have any of the things that most human beings find comfort and strength in – then I wonder how many of our fledgling activists will be able to continue fighting the fight as they get into their twenties and thirties. You should be able to save the world and have enough money to get a taxi. You should be able to save the world in your forties from your own house, supporting your own children, if you so choose.

We need to live in a post-martyr age for excellent, revolutionary young women.

Caitlin Moran

If Thunberg is fighting to raise awareness of how we can save the world, one of the ways we can help her is fighting to raise awareness of what a shitty deal we still give our young girl heroes. We can defend them as if they were our own daughters.

October 2022

It’s now four months later, and Greta Thunberg is standing outside her university on a sunny yet cold evening on a break between lessons. We’re catching up on what she’s been doing since Glastonbury, as the publication of her book draws closer. There’s a lot to discuss. Pakistan has suffered its worst floods in recorded history, likewise Florida; both southern France and Canada have been consumed by wildfires; Britain now has a prime minister who is planning to restart fracking – and “Greta Thunberg” has trended globally once more on Twitter. Why? Because Donald Trump Jr has just retweeted a meme accusing her of being the one who sabotaged the Nord Stream gas pipeline.

“Did he actually do that? I did not know!” Thunberg starts laughing – a properly joyous laugh – for nearly a minute. “That’s so funny!”

“That family really have problems with you,” I say. “They are obsessed.”

“Yeah, of course I did it. I bombed it with my sign,” Thunberg says before laughing again.

I’m glad she’s laughing. I thought she already knew, and it’s generally considered Bad Celebrity Etiquette to be the first person to tell someone that they’re trending on social media. It’s a bit like reporting back bad gossip to someone, but when the whole world

is gossiping about you. Still, given that I’ve already done it, I have another piece of news to tell her: there is another conspiracy theory doing the rounds – that she has a fortune of more than $1 million.

“Yes,” Thunberg says, sighing. “That is because I won an award that was worth 1 million euros. I have won many awards that are worth even more in total, but I’ve donated all my money. Of course, they don’t care about that.”

This conversation about money allows me to bring up what I’ve been fretting about since I met her in June: that, to avoid accusations of hypocrisy, young activists must sacrifice any hope for a “normal” future life. Thunberg meets the question calmly, head on.

“I don’t allow myself to think of these things,” she says simply. “All I can think is that, right now, I have everything I need. I have somewhere to live and food and access to basic things.”

“But doesn’t it make you… angry or sad that you have to give up so much? Don’t you just want to… run away from it all?”

Thunberg pauses. “I don’t think so,” she says finally. “Of course, it would be nice to just go into the forest and not do any of this, but that’s not going to happen.” She pauses again.

I imagine her – a teenage student, standing outside her university between lessons, talking to the international press instead of vaping by some bins like a normal young person.

“But we’re not doing all this because we want to,” she continues. “We’re doing this because… it seems like you have to do something.”

And she is, of course, right. I keep thinking of the line in Don’t Look Up

where – just before the long-ignored, infinitely avoidable comet hits, obliterating Earth – Leonardo DiCaprio says, with an unbearably simple sadness, “We really did have everything, didn’t we? When you think about it.”

We go on to chat a while longer – about her least favourite subject at school (“Economics. It is just… this thing that we humans have made up and we now worship it”), and the current project that estimates that, by 2025, humans will be able to talk to whales.

What do you think whales will reply when asked, “What do you think of humans?” I say to her.Thunberg, with exquisite dry humour: “I guess it will depend on the individual whale.”

Our time is up and I thank her – then go and have a quiet cigarette, thinking about just what she is doing and at what cost. After a few minutes I open The Climate Book and there is a quote from her that I read again: “Right now, we are in desperate need of hope. But hope is not about pretending that everything will be fine. To me, hope is not something that is given to you, it is something you have to earn, to create. It cannot be gained passively, through standing by and waiting for someone else to do something. Hope is taking action. It is stepping outside your comfort zone. And if a bunch of weird schoolkids were able to get millions of people to start changing their lives, just imagine what we could all do together if we really tried.” Hope isn’t just a noun. It’s a verb. We have to do hope. We really could have everything. When you think about it.

This article first appeared in The Times. Reproduced under licence.