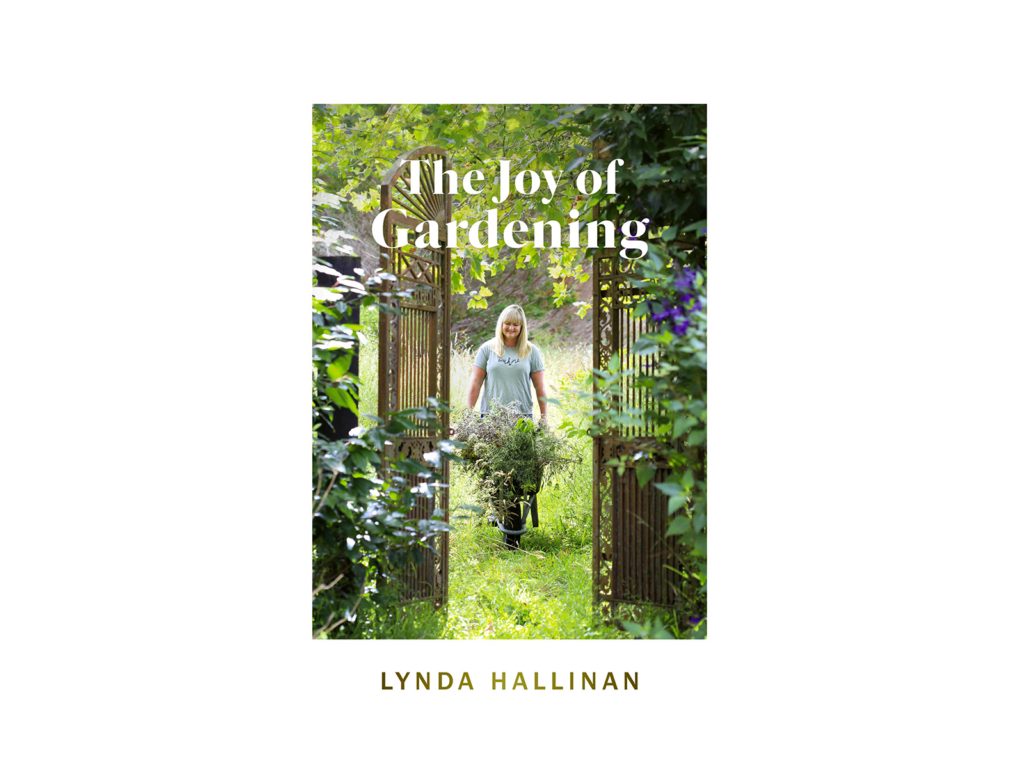

In this extract from her book, The Joy of Gardening, Lynda Hallinan rethinks annoying invaders and finds beauty in her lazy-woman’s lawn.

Of all the things I do in my garden, weeding is the only truly thankless task – and even it has some perks. As a mindfulness exercise, the benefits of weeding can be measured by the wheel barrow-load. As Great Dixter’s Christopher Lloyd once said, “Effort is only troublesome when you are bored.”

I get my best ideas while sending petty spurge (Euphorbia peplus) packing with a push hoe or yanking out clumps of clingy cleavers (Galium aparine), although I forget most of them by the time I finish pulling and pushing.

Some weeds don’t put up much of a fight. Chickweed, scrambling fumitory, henbit deadnettle and death-comes-quickly (Geranium robertianum) are almost a pleasure to rip out. Also known as herb-Robert, this geranium flourishes along the south side of our house in the gravel path leading to our water tank. We rarely walk this way as it takes offence when trodden on, releasing an acrid smell like burning tyres.

When my garden was open to the public I felt compelled to maintain appearances and evict the weeds, but since the Covid-19 lockdown I’ve learned to let them be, aside from cutting off their heads before they shed seed. There are better ways to do battle than with chemical warfare, for not a single weed species has ever been eradicated by herbicide. If anything, our use of garden sprays has made them more belligerent.

Ecologists who compared centuries-old herbarium specimens of Oxford ragwort, winter speedwell and willowherb to their modern-day incarnations found that these cunning invaders are still evolving. Ragwort, for example, is now 20 percent taller, with a similar increase in leaf area, than it was when brought to Britain from Sicily around 1700.

If you must, move weeds along gently. Use non-systemic weedkillers with base ingredients such as coconut oil, pine or fatty acids to snuff them out without contaminating the soil. Smother creeping weeds with cardboard or wool, or steam them under black polythene for a season. It takes more effort to shift tenacious tap-rooted and perennial weeds; hire students or start a sweat-equity exchange with friends.

As the British celebrity gardener Monty Don says, plants become weeds only by virtue of their success. It’s hardly their fault that we want fewer of them hanging around our homes. Like every other living thing on the planet, they’re just trying to survive, make ends meet, have some kids. They’re just trying to get by.

I do love a perfect lawn, a groomed sward soft enough to loll about on or to sink bare feet into without fear of prickles or bees on clover. A decade ago, I even got married on a perfect lawn: ours.

But 10 years and not a whiff of herbicide later, our lawn sports significantly more weed growth than grass, including creeping buttercup, dandelions, daisies, hydrocotyle, Ōnehunga weed and sorrel.

I could douse it with a Weed ’n’ Feed panacea, those cure-all combinations of nitrogen-rich fertilisers and broadleaf herbicides that give life with one hand and take it with the other, but chucking about chemicals offends my organic sensibilities. I could also get down on my knees and weed it, but that offends my lazy streak.

And anyway, perfect lawns are for conservative, conformist aesthetes – most of whom, dare I say it, are men. I’ve had friends open their gardens for charity only to have uncharitable sods point out, to their faces, that the lawn could do with a bit of work.

In suburban gardens, I concede that tidy lawns can be seen as a civic duty – nothing speaks to neighbourly dissent quite like a verge mown to exactly the halfway point between two driveways – but in the country no one cares how long or unkempt your lawn is. I’ve come to think of mine as a small, tidy paddock rather than a large, overgrown lawn.

A few years ago, I abandoned all hope of restoring our lawn to its former glory and fenced it off for my children’s Ag Day pet lambs, Maisy and Lucy. They were followed by a hand-raised clutch of 10 ducks and nine chooks, after which came a drought and Covid-19. These days, my lawn’s liberation is something to celebrate. When I shared a photo on Facebook of the knee-high grass, infiltrated with bristly oxtongue, hawksbeard and wine-barrel hen houses, it got 1500 likes (and 109 laughing emojis).

There is no such thing as a lawn in nature, let alone fine fescue stripes or a bowling green of creeping bent. Lawns are environmentally reckless and create work for no reason, for the more a lawn grows, the more insistently we mow it. It would be funny if it wasn’t all so pointless.

No one likes a monoculture, not even grass-fed animals. Whenever our dairy cows got into my parents’ garden, they always made a beeline for the flavoursome flower beds and shrubs, while revelling n the rebellious delight of trashing and trampling the lawn in spite.

What happens to a garden when we stop trying so hard? “It will look like hell, of course,” quipped the American entomologist Eric Grissell in his 1986 book Thyme on My Hands. But plants – weeds, mostly – will still grow nicely, and what right do we have to condemn them?

Where gardeners see weeds, herbalists and foragers see old friends. Many weeds are masterful impersonators; how often have I turned a blind eye to an inkweed seedling, mistaking it for a spring dahlia shoot, or a self-sown roadside verbena, thinking it a cultivated hybrid of purpletop vervain (Verbena boniarensis). This sibling rivalry also works in reverse; my father once mistook the eerie blue globes of Echinops ritro for Scotch thistles and sprayed them.

“A weed is a plant that is not only in the wrong place, but intends to stay,” said the ecologist Sara Stein, who coined the term “ungardening” in her eloquent 1993 book Noah’s Garden. She urged the restoration of ecology to American backyards, advising readers to fling wide their garden gates and “loosen the land’s aesthetic corset, let it be more blowsy and fecund, allow it to bed promiscuously with beasts and creatures of all sorts.”

More recently, British conservationist and farmer Isabella Tree has inspired a rewilding revolution, while closer to home my friends at Curious Croppers in Clevedon, Anthony and Angela Tringham, have adopted an agro-ecology ethos for their heirloom tomato hothouses.

They’re big on beneficial insects. One year, Anthony showed up at my garden to liberate a plastic vial of teeny-tiny Tamarixia trioaze. This parasitic wasp is an enemy of the tomato/potato psyllid, a pest that breached our borders a decade ago and now routinely wrecks outdoor crops of both plants.

When Anthony and Angela surrounded their hothouses with biodiverse borders of purple tansy, basil and buckwheat to create habitats for their bio-control workforce, guess what happened? All the bumblebees they’d bought to pollinate their tomatoes fled their hothouse hives in favour of an orgy in the outdoor flower garden.

In a garden, you have to accept all of nature, even when things don’t go to plan.