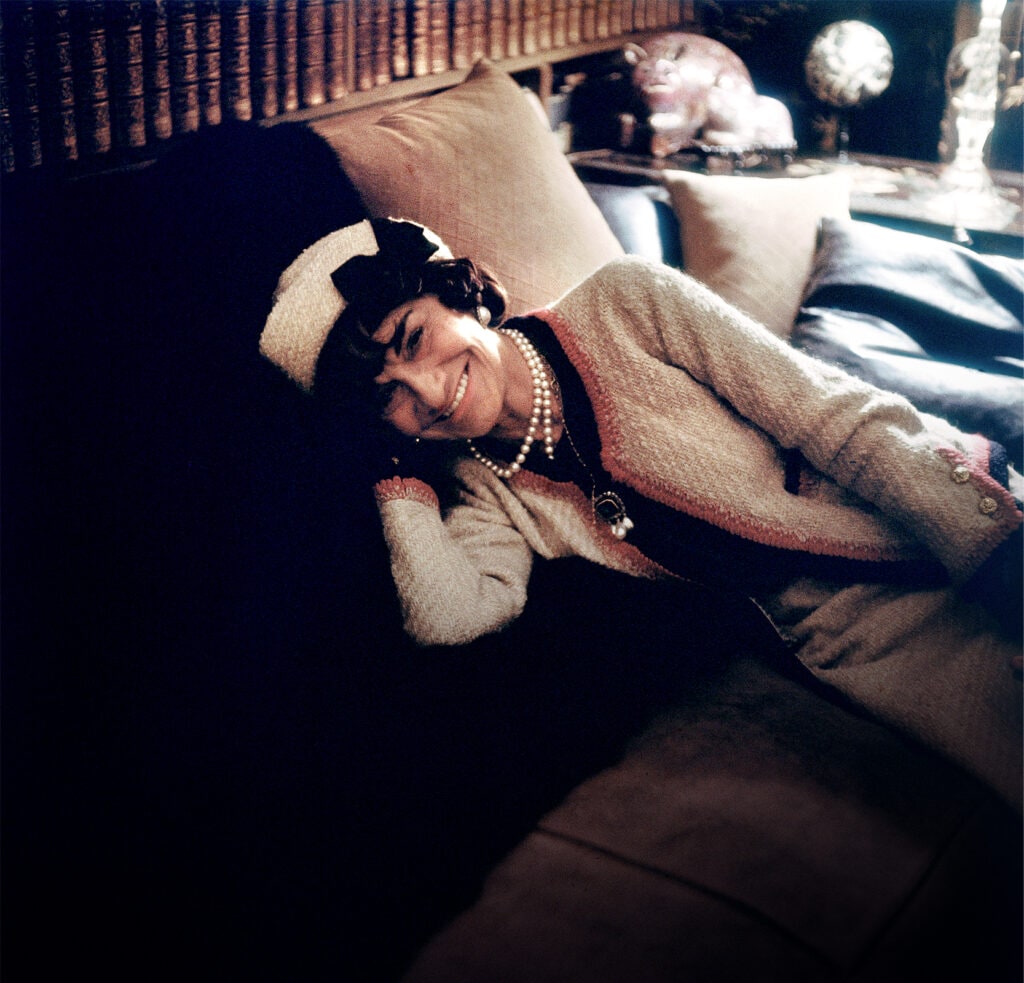

It’s 50 years this month since the death of legendary designer Coco Chanel. Her impact on the fashion world was huge, but, as Donna Fleming reports, for much of her life she hid a scandalous secret.

It seemed like a wonderful idea at the time. After Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel died, aged 87, on January 10, 1971, her good friend Claude Pompidou – wife of French president Georges Pompidou – suggested a special tribute to the iconic fashion designer. Why not celebrate her life and work with an official exhibition? It would be a most fitting way to honour the legendary couturier.

Others agreed and a date was set aside for a grand opening the following year.

But then someone had a quiet word with Mme Pompidou. Rumour had it that Pierre Galante, an editor at Paris Match magazine – and husband of British movie star Olivia De Havilland – had some shocking information about Coco and the German aristocrat she’d had a relationship with during World War II.

Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage was not an innocent bystander to wartime activities, according to files Pierre had unearthed – he’d been a German agent, possibly with the Gestapo, and Pierre was planning to write a book revealing the truth.

Coco’s affair with the German was no secret – it had been the subject of much gossip for years and she’d been questioned about it in court after the war. But there had never been any repercussions and Coco had been free to later relaunch the business she’d closed at the start of the war, her dalliance with the enemy all but forgotten.

However, consorting with a member of the Gestapo was next level when it came to frowned upon behaviour. The war may have ended a quarter of a century earlier, but there was still anger and hatred directed at those who had collaborated with the Germans.

So the plug was pulled on the exhibition. Pierre went on to write his book, Mademoiselle Chanel, including in it the damning information about her German friend that had apparently come from French counterintelligence services.

It was to be another 40 years before an even bigger bombshell was dropped. According to newly declassified information uncovered by veteran investigative journalist Hal Vaughan, it wasn’t just the baron who had Gestapo links – Coco Chanel herself had been a fully-fledged agent in Abwehr, the German military intelligence service. She worked directly for the Nazis and had her own number and code name.

The shockwaves from this news not only rippled throughout France, but also the international fashion industry. Coco Chanel was revered – she had given the world the little black dress, the classic Chanel suit, the quilted handbag and Chanel No. 5 perfume. She was regarded as the epitome of French taste and style, a visionary whose designs are still in demand today. How could she have been a traitor?

The fashion house she’d established was quick to dispute the claims in Hal’s book, Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War, saying that her connection with the baron was simply a poorly thought-out liaison. In a statement it said, “What’s certain is that she had a relationship with a German aristocrat during the war. Clearly it wasn’t the best period to have a love story with a German, even if Baron von Dincklage was English by his mother and she knew him before the war.”

But there were records, found by Hal, that showed Coco was Agent F-7124, code name Westminster, and had been on several missions around Europe for Abwehr to recruit new agents for the Third Reich.

So why had she led this double life? Why betray her country? In an interview with The New Yorker, Hal, who has since died, recalled a conversation he had with Coco’s great-niece, Gabrielle Labrunie. “She said to me, ‘You know Mr Vaughan, these were very difficult times, and people had to do very terrible things to get along’.

Chanel was, very simply put, an enormous opportunist who did what she had to do to get along.

That description not only sums up Coco’s actions during the war, but throughout her whole life. She was a survivor who grew up conditioned to put herself first, because there was nobody else to do it.

Designing her destiny

Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel was born into poverty in Saumur, France, in 1883. Her mother Jeanne worked in a laundry; her father Albert was an itinerant street vendor who travelled around rural towns, peddling clothes and undergarments.

Gabrielle’s parents weren’t married and her maternal grandparents had to pay Albert to make an honest woman of their daughter a year after Gabrielle arrived. Albert would disappear for months at a time, supposedly to work, and Jeanne, who was often ill with tuberculosis, struggled to cope with their five children on her own.

She died when Gabrielle was 11 and, shortly afterwards, Albert abandoned his motherless children. Gabrielle ended up in an orphanage run by nuns where, in harsh conditions, she was taught to sew and embroider linens. The attempts of the often sadistic nuns to break her spirit only served to make her more determined to take control of her own life.

At 18, she left the orphanage to live in a boarding house in Moulins, in central France, and got a job in a draper’s shop, where her duties included tailoring. She was good at it, but she had greater ambitions. She began singing at a local cabaret and it was here, in 1904, aged 21, that she earned the nickname Coco. One theory was that it’s because she was known for singing a song called “Who’s Seen Coco At The Trocadero?”.

The other was that it was based on the French word for mistress: cocotte.

Her stage name became La Petite Coco but her musical career didn’t take off, possibly because her singing voice left a lot to be desired. But the military patrons at the café found her attractive and alluring, and one in particular became smitten.

As luck would have it, former army officer Étienne Balsan was fabulously wealthy, thanks to an inheritance left by his late parents. When he suggested Coco live with him as his mistress at his chateau, Royallieu, she did not hesitate. Étienne was to be the first in a long line of lovers (she never married) who she would use to better her fortunes.

Her life changed overnight. She spent her days lounging around the chateau, visiting and hosting Étienne’s friends, partying and learning to ride (Étienne bred and trained horses). A friend of Étienne’s remembered Coco as “a tiny little thing, with a pretty, very expressive, roguish face and a strong personality. She amazed us because of her nerve on horseback but aside from that, there was nothing remarkable about her.”

Despite living the good life at Royallieu, Coco wasn’t happy. She wanted to be more than a kept woman. And then she did something that was to set her on a remarkable path in life: she decided to “tart up” the boater hats she wore for riding. Her efforts were much admired by her friends, who asked her to decorate hats for them, and Coco persuaded Étienne to give her the money to start a millinery business.

In the meantime, she had started an affair in 1908 with one of Étienne’s friends, wealthy upperclass Brit Captain Arthur Edward Capel, known as Boy.

She eventually ditched Étienne for Boy, who installed her in an apartment in Paris and financed her first shop.

Their romance continued even after he married another woman, and only came to an end when Boy was killed in a car crash in 1919. Later Coco confided to a friend, “His death was a terrible blow to me, I lost everything. What followed was not a life of happiness.”

But it was one of great success. Her shop on rue Cambon, Paris, which opened on January 1, 1910, did well.

By 1913, with Boy’s help, she had opened a second store in the resort town of Deauville. This time, she branched out from hats to include deluxe casual clothing, “suitable for leisure and sport”.

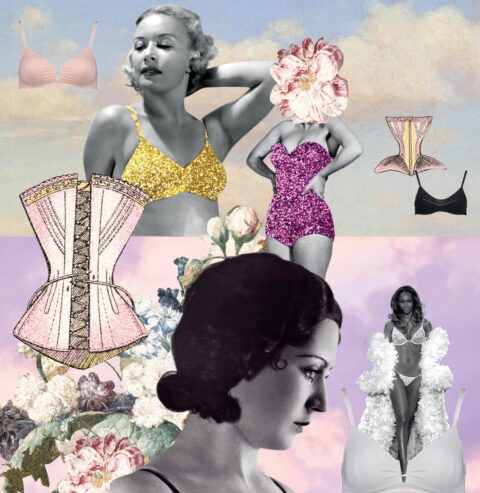

Coco’s clothing was notable for being made from humble but comfortable fabric like jersey, usually used for men’s underwear. Fed up with fussy dresses and restrictive corsets, she designed jackets, jumpers and blouses that were simple but elegant, and also quite masculine in style. She took many of her ideas from Boy’s wardrobe, including his classic jackets. A skirt, jumper and cardigan in neutral shades became her first signature outfit.

By the time World War I ended in 1918, Coco had opened another boutique in another resort town, Biarritz. Business was also booming in Paris, and she ended up buying five properties on rue Cambon for her ever-expanding empire.

Relentlessly ambitious, in 1921 Coco had a brainwave – she wanted her own fragrance.

She once said that perfume “is the unseen, unforgettable, ultimate accessory of fashion, that heralds your arrival and prolongs your departure”.

The scent had to embody the liberated feminine spirit of the 1920s, she told master perfumer Ernest Beaux. Using a base of rose and jasmine, he came up with 10 different samples. After sniffing all the vials, Coco said to Ernest, “Number five. That is what I was waiting for.”

As modern and appealing as Chanel No. 5 was, it was the bottle that helped to make it a best-seller. Coco was not a fan of the elaborate crystal fragrance bottles produced by the likes of Lalique and Baccarat. It’s thought the striking design of her bottle was inspired by Boy and based on either the square shape of his favourite toiletry bottles or the whisky decanter he used.

The perfume, coupled with her innovative clothing, made Coco very rich and internationally famous. She embarked on a series of relationships with men who were also well-known, including a year-long affair with Russian Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, cousin to Tsar Nicolas II and one of the men involved in the killing of “mad monk” Rasputin.

After meeting ballet founder Sergei Diaghilev and composer Igor Stravinsky (with whom she had a brief fling), Coco designed dance costumes for the Ballet Russes. She also became friends with artist Pablo Picasso, another of her conquests, and poet and playwright Jean Cocteau.

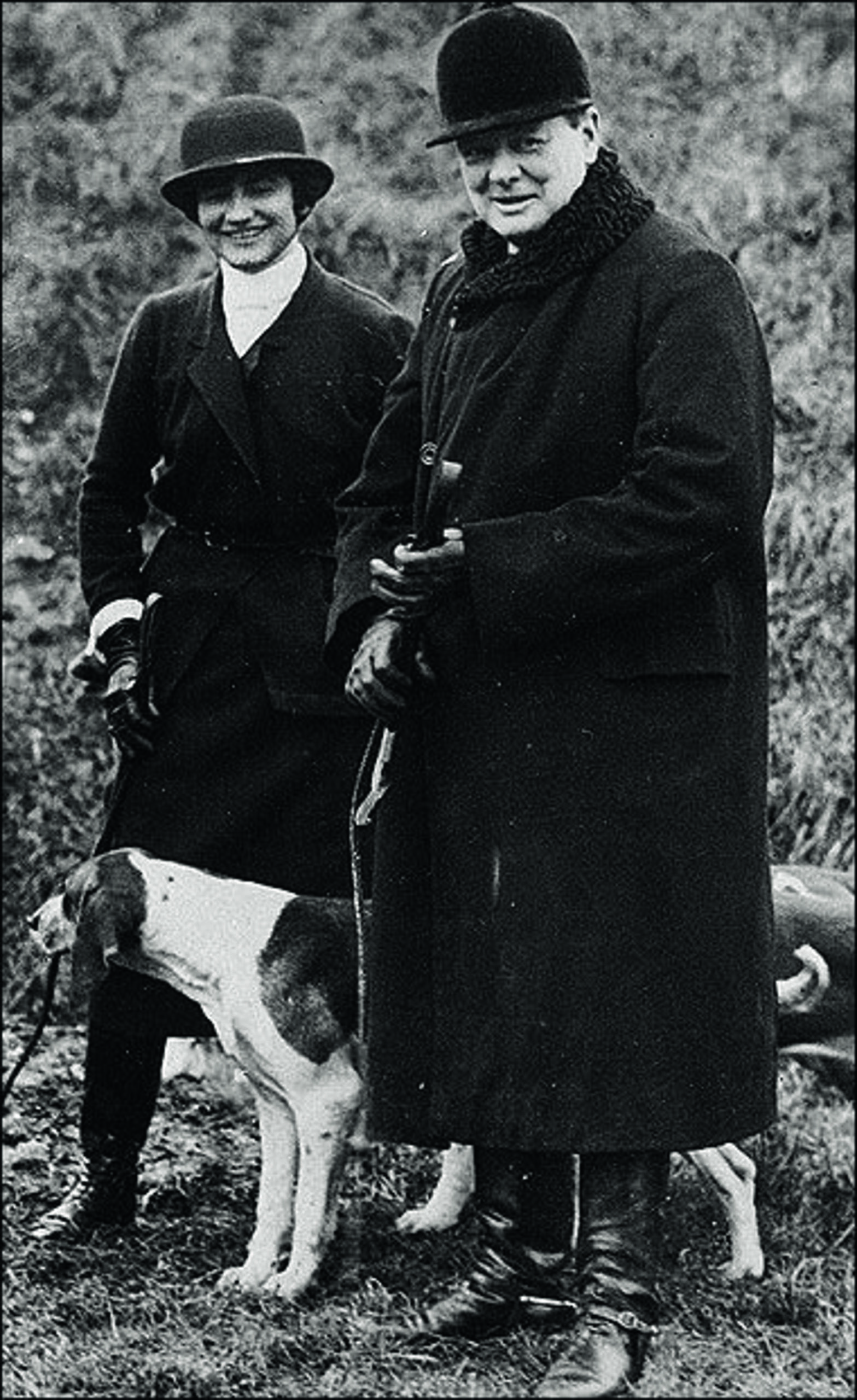

In 1923, Coco was introduced to several prominent Brits, including politician Winston Churchill, the mega-rich Duke of Westminster, Hugh Grosvenor, and the Prince of Wales – the future King Edward VIII.

The prince – who was yet to meet American divorcee Wallis Simpson – was said to be besotted with Coco and they enjoyed a “great, romantic moment together”, according to Vogue editor Diana Vreeland. But Coco was already involved with the Duke of Westminster, who owned great swathes of central London. He bought her a grand home in Mayfair and land on the French Riviera, where she built a villa. He also showered her with expensive jewels and art. Married to his second wife when he met Coco, Hugh divorced a year later but did not marry his lover. Instead, after four years as a single man, he wed baron’s daughter Loelia Lindsay. Yet he and Coco continued their affair, finally parting ways in the mid-1930s after 10 years together.

When asked why she never married Hugh, Coco retorted, “There have been several Duchesses of Windsor. There is only one Chanel.”

The 1920s were wonderful for Coco. Along with her perfume, she came up with the concept of the little black dress – until then, black was the colour of mourning, not evening wear. The Chanel suit, with its slim skirt and collarless jacket, first made its debut in 1925, inspired by the sportswear favoured by her lover, the Duke of Westminster.

But by the 1930s, she was no longer fashion’s golden girl. Paid a million dollars by movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn (approximately $110 million today) to design costumes for Hollywood, her “less is more” aesthetic did not translate well to film and the whole experience was a disaster.

Back in Europe, her position as queen of haute couture was usurped by the new darling of the fashion world, Italian Elsa Schiaparelli. Plus, her designs for a Jean Cocteau play were mocked as making bandage-wrapped actors look like “ambulant mummies, or victims of some terrible accident”.

By the mid-1930s, Coco was using morphine on an almost daily basis, describing it as a “harmless sedative”. When war broke out in September 1939, she saw it as the perfect opportunity to close her business, costing 4000 female employees their jobs.

She moved into a suite at the Ritz Hotel with the new man in her life, Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage, and secretly launched her spying career.

Previously outspoken about her anti-Semitic views (which had been fostered by the Duke of Westminster), she was ripe for recruitment by the Nazis. She reported to General Walter Schellenberg, chief of the German intelligence agency.

Coco was directly involved in a plan for the Third Reich to take control of Madrid, and travelled to Spain more than once to try to recruit spies. She also went to Berlin to offer her services to Heinrich Himmler. Her relationship with Hans raised suspicion and following the war, she was brought before French authorities to be questioned about her wartime activities. A French traitor who had spied for the Germans spilled the beans about what Coco had done, but she somehow managed to wriggle her way out of trouble and was never prosecuted, unlike 160,000 other French collaborators.

There was much speculation – fuelled by admissions from Coco’s family after her death – that she had Winston Churchill to thank for that. Some historians claimed he instructed the British ambassador to protect her, partly because of their longstanding friendship, but also because it was feared that she could expose certain British officials, aristocrats and members of the royal family who were pro-Nazi.

With no consequences to face, Coco fled, along with Hans, to neutral Switzerland. She was careful to cover her back. When she heard a dying General Schellenberg was writing his memoir, she paid his medical bills and ensured his family were taken care of financially. When the book was published, there was no mention of her.

Coco stayed out of the limelight until 1954 when, aged 71 – and after 15 years away from the fashion industry – she staged a bold comeback.

Annoyed with the emergence of designers like Christian Dior and Cristóbal Balenciaga who created dramatic fashion, she rebelled against these men who were putting women in “waist cinchers, padded bras, heavy skirts and stiffened jackets”.

She updated her Chanel suit and a quilted handbag she’d first produced in the 1920s, and Chanel couture was back in business. Coco was still working up to the day of her death, preparing her spring catalogue.

Throughout her life, she had been famed for her pithy quotes, like “Fashion changes but style endures” and “Simplicity is the keynote of true elegance”.

But knowing what we know about Coco Chanel now, the one line that perhaps sums her up best was, “I don’t care what you think of me. I don’t think of you at all.”