For Pacific theatre pioneer Nina Nawalowalo, storytelling is a way of life. She tells Dionne Christian about the healing power of art and her hopes for the future.

From performing in villages in Poland to the forests of the Solomon Islands and on to some of the world’s most famed playhouses, Nina Nawalowalo has one of the most remarkable careers in New Zealand theatre.

Not only is she the world’s first female theatre director of Melanesian descent, there are few others who have toured the world with champion magicians – and won awards for it – then co-founded an award-winning theatre company in Wellington (The Conch, with husband Tom McCrory) to find new ways of telling Pacific stories, especially those of women.

PHOTO BY JAMIE WRIGHT

“My journey of working with Pacific women in theatre came from the fact that there weren’t a lot of roles for Pacific women, so we felt we had to tell our own stories and explore the whole way to represent ourselves on stage,” Nina says.

“There are so many layers to Pacific women, but we’re portrayed in New Zealand in certain ways. I wanted to look at the whole cultural, spiritual, ancestral lines which can come in many forms. There’s beauty in the depth of the female, so it’s very important to show the many, many layers of what women do.”

Eight years ago, Nina and Tom established a women’s theatre company in the Solomon Islands called Stages of Change – originally a one-off project with the British Council to address violence against women and girls. That venture has now developed into a permanent and sustainable enterprise for the Solomon Islands women involved in it.

IMAGE SUPPLIED

It’s the kind of life-changing theatre that opens doors, and using theatre as a vehicle for social change is one of the driving forces in Nina’s life. She was recognised for this in 2017 with the Senior Pacific Artist Award from Creative New Zealand and, a year later, was made an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

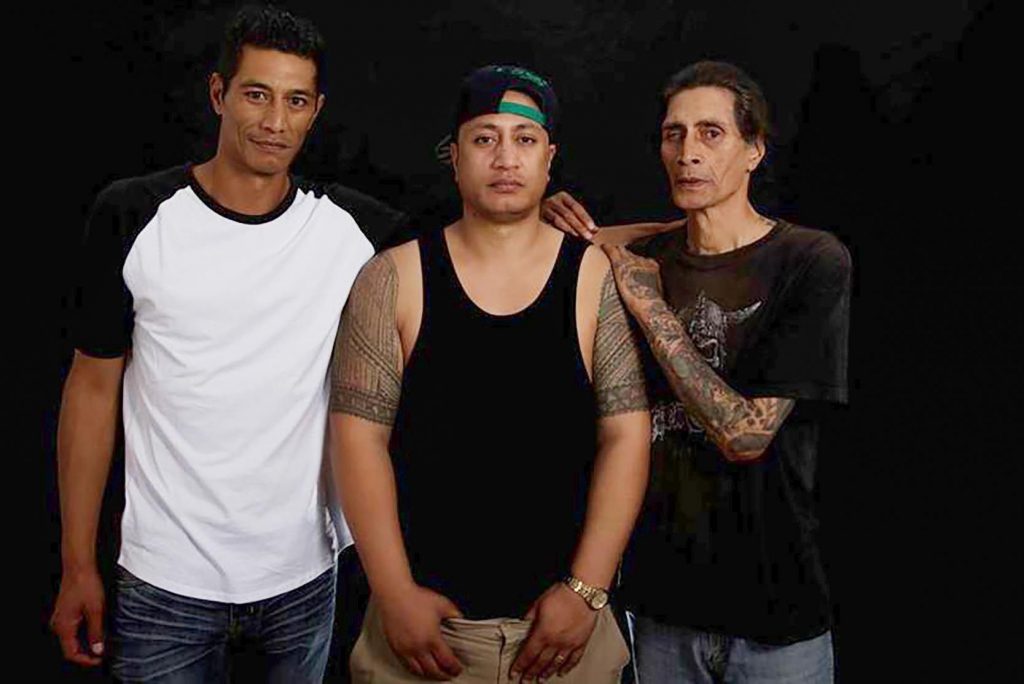

When we talk via Zoom about her latest project, Nina and Tom are with writer, musician and actor Fa’amoana John Luafutu, and their surroundings are unassuming. The trio sits on a couch in the living room of Nina and Tom’s home, laptop in front of them, vacuum cleaner behind. It’s an apt visual metaphor for the dual lives of creatives – often occupied at home with work, domestic and family responsibilities.

IMAGE SUPPLIED

They’re talking about their latest collaboration, A Boy Called Piano. Written by Fa’amoana – father of sons Matthias, an actor, and Malo, better known as rapper Scribe – it gives voice to the thousands of Māori and Pacific children who were abused in state care.

Fa’amoana, 67, was one of those children, the boy called Piano, and it has “ taken him years to overcome the shame he experienced at “taking his father’s name into papers on the court pages, rather than for scoring a try”. Instead of the family’s surname being in print for an achievement to be celebrated, it was there because Fa’amoana was appearing in court. He says he couldn’t have written about these events without Nina and Tom, who have put their arms around him figuratively and literally.

“It was like psychodrama in public. It was a good thing I had people like Tom and Nina who sort of had their arms around me during the process; there are times when you just let go and you cry,” says Fa’amoana. “It was really painful but cathartic for me, as a writer, to live those things about a part of me that I tried so hard to suppress way down in my gut.”

A Boy Called Piano grew out of the award-winning play The White Guitar, directed by Nina alongside renowned actor/director Jim Moriarty and featuring Fa’amoana, Matthias and Scribe. Critics praised it as “a seminal moment in New Zealand theatre history”.

IMAGE SUPPLIED

And although that show appeared to be the story of a father and two of his sons, Nina says it was very much about women and the power of mothers and grandmothers to hold families together.

Fa’amoana adds, “In our culture, women always took the back role – when the missionaries came they were relegated to faletua which means “back of the house”. They might be called back of the house, but without that there’s no front of the house, either.”

But making The White Guitar exposed other hidden histories, like Fa’amoana’s own as a state ward in the 1960s. Nina and Tom, parents of three children now in their twenties and teens, wanted to take Fa’amoana’s story to the stage to highlight the vulnerability of children who were put in care and had their trust destroyed – “and what that does to a child” – coupled with the flow-on effects it’s had on all New Zealand.

A Boy Called Piano debuted in Wellington in 2019, coinciding with the launch of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, but plans to tour the country were halted when Covid-19 hit, so The Conch “pivoted” and seized the chance to tell the story as an audio play.

Nina says they were lucky that financial supporters, such as the Performing Arts Network of New Zealand (Tour-Makers) and Auckland Live, stayed with them, while musician Mark Vanilau had the skills to make a production work as a radio play. Nina believes the radio adaptation will draw in people who might not come to this kind of work in the theatre and says it’s the first time the experience of those in state care has come directly to New Zealand listeners, told by a man who lived it.

How different life might have been for Fa’amoana, and other children put into state care, if they’d had teachers like Nina. For it was at Wellington Teachers’ College and in primary school classrooms where she saw first-hand art’s power to transform lives.

Nina’s father, Ratu Noa Nawalowalo, came to New Zealand in the 1950s, shared a house with a budding Samoan writer called Albert Wendt (who later encouraged Fa’amoana to keep writing) and became the first Fijian-born barrister to graduate from Victoria University of Wellington. He met her mother, an English nurse called Mary Tancock, at the Wellington Chess Club. Nina says there are plenty of pictures of the early days of their courtship as Mary was flatting with young photographer Ans Westra.

Nina recalls her early years spent playing chess, traveling to Fiji, where the family lived for a few years, then returning to Wellington, where she became a high school basketball champion, representing New Zealand.

It was “incredible lecturers”, who included arts and creativity in their programmes at teachers’ college, who got Nina hooked on theatre. She taught for 18 months at Porirua’s Maraeroa Primary School and says educating children – often those who, like Fa’amoana, had English as a second language – encouraged her to look for ways to teach other than sitting on the mat and rote learning.

“How one reads or learns how to teach children, it comes, for me, from a deep love of children. That’s the essence of A Boy Called Piano; the child is so precious, so it’s about how to make the audience see a child and feel for a child without the judgement of how one gets there and what’s happened. It’s about the nurturing and the purity of what a child is in this world.”

In the early 1990s, Nina joined a New Zealand delegation of young people to perform at an arts festival in Russia. It was the start of years spent in Europe, doing things as adventurous and disparate as performing mime productions in Polish villages, studying mime in France and commedia dell’arte in Italy, joining a North London Afro-Caribbean basketball team and teaching part-time in culturally diverse London schools to earn the money to pay for more theatre, mime and magic training.

IMAGE SUPPLIED

“I thought I could teach in New Zealand, but going into cultural, inner-city London schools where there were children who had suffered trauma or had different difficulties – wow, I had some wonderful experiences…

“When you have a whole classroom full of children not listening to you and nothing works that you have tried you have to think, ‘How do I get creative?’ So I did art! I did a lot of drama with them, some film-making. Because I was linked to the theatre world, I got people to come in and they did interviews and workshops. It was about thinking of other ways to look at education rather than ‘You’ve got to sit at a desk.’”

Nina likens teaching to theatre directing and being prepared to draw upon and experiment with a range of things to see what will allow you to best tell a story. She says theatre opens up a space for exploring issues that can otherwise be taboo – but there should always be elements of magic.

“I love magic and that’s something I love to draw inside the work. And the element of surprise. Children – human beings – love that element of surprise. I love that you can use visual elements, visual magic, inside a story, but it’s not like a trick or a hook. It’s a vehicle to blend European styles of theatre with Pacific storytelling. It opens up a world so you don’t have to be a Pacific Islander, you don’t have to be from there, to look in and experience your own feelings.”

A Boy Called Piano will be broadcast on Radio New Zealand’s Standing Room Only, May 2 at 3pm. It will also be available on RNZ’s website until May 16.