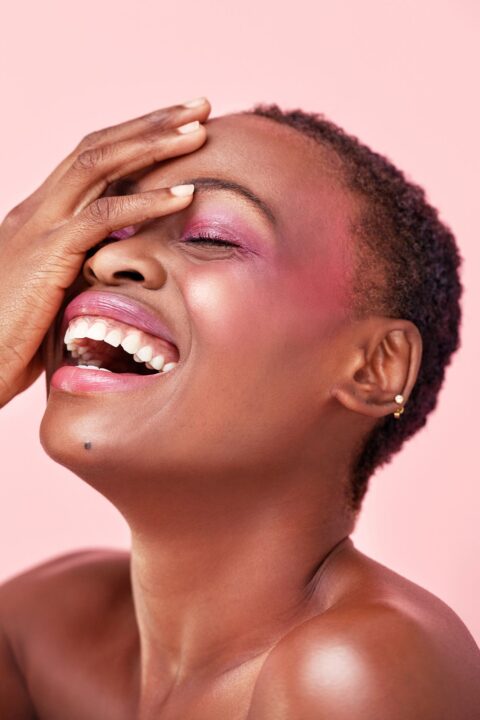

A Kiwi entrepreneur tells Sharon Stephenson her planet-saving period-proof pants are also all about breaking down secrecy and shame about menstruation.

Most women have a story to tell about leaking periods. Of the sweater tied around the waist, the raincoat worn indoors or the emergency dash home to hide the “accident”.

It wasn’t uncommon for my generation, or previous ones, to be taught that periods were something to be hidden. It’s a narrative that lingers today, with a 2019 survey showing three out of four Kiwi women admitted that having a period was viewed as shameful.

The survey, conducted by menstrual products company Libra, found that menstruation was more stigmatised than drugs, sex or STDs and that more than half of 13-17-year-old girls said they would rather fail a school test than have their classmates know they’re having their period.

They’re figures that shocked Aucklander Michele Wilson (Tainui, Ngati Pāoa), co-founder of the trailblazing Kiwi period underwear company AWWA.

“Sadly, there are still stigmas and taboos that exist around periods today,” says Michele, 38. “But we’re slowly breaking them down and we’re glad to be part of the period revolution that’s happening globally.”

Part of that is thanks to growing recognition of the ruinous environmental impact of single-use menstrual products such as tampons and pads. The UK’s Women’s Environment Network, for example, estimates that up to two billion menstrual items are flushed down toilets in Britain alone each year.

For Michele, who co-founded AWWA with her friend and fellow entrepreneur Kylie Matthews, breaking down the embarrassment around periods and being more sustainable were two of the triggers to starting the company, which provides period-proof underwear that can hold and absorb up to five regular pads or tampons worth of blood.

The other was a desire to reconnect with her Māori heritage, and particularly the way her ancestors approached their periods (waiwhero).

While studying rongoā (Māori medicine) the former lawyer realised that in early Aotearoa, having a period was seen as a cause for celebration and acknowledging the connection between people, the land and ancestors.

“When waiwhero first arrived, there would be the giving of gifts. Moko kauae would be given, there would be a ceremonial cutting of hair and piercing of ears and the community would get together to share kai. Our tūpuna believed our menstrual blood carried our ancestors and that bleeding straight onto the land was a sacred gift to the mother, to Papatūānuku.”

Yet research shows that following the arrival of church missionaries and the adoption of tauiwi (non-Māori) thought and customs – especially that the menstrual cycle and menstruating women were seen as unclean and unholy – the cultural practice of periods being sacred went out the window.

It was something that didn’t sit right with the mother of daughters Eva, 10, and six-year-old Frankie, who started to investigate traditional methods of dealing with her monthly blood flow a few years ago.

She learned that mosses such as angiangi and kohukohu were traditionally used to make menstrual pads and that plants such as karamū and puka were used to ease period pain.

So Michele started gathering moss to use during her periods. But when her period arrived while on holiday in Rarotonga in 2017, and there was no moss to be found, Michele decided to free-bleed.

“I kept thinking, why isn’t there a better way to manage our periods? Why hasn’t someone come up with a reusable pair of period pants that don’t leak, smell, add to landfills and are convenient and easy to use?”

Making it happen

Back then, no one was making a product like this, leading Michele to call her friend Kylie Matthews, suggesting they combine their entrepreneurial talents in a period pants company. “I was so excited I went straight to Kylie’s place from the airport,” she recalls.

A year of research and development followed, finding the right environmentally friendly materials that would lock in liquid and prevent it from leaking out the sides. They settled on a three-layered product that traps liquid, is antimicrobial and has no odour.

Michele designed the underpants to look like “normal” underwear. Their search for an ethical, sustainable manufacturer experienced in making undergarments took them to Sri Lanka, where they found a family business with a home-based factory. Four years later, that family is still their main manufacturer.

“They now have two factories and work exclusively for us. We’ve also found an ethical manufacturer in China and are now looking for a third.”

The friends named their company AWWA, which means flow or divine river, and initially envisaged it fitting around their other work. But success was swift and shortly after making their first sale at the end of 2018, they sold their respective businesses and ploughed the funds into AWWA.

As well as being a hit in Australasia, their 14 styles are now sold around the globe, including all 50 US states, Asia and Europe. “We’re especially popular in Scandinavia,” says Michele.

Forging her own path

For Michele, it’s the fulfilment of a dream that so many told her wasn’t possible. The born-and-bred Aucklander grew up enmeshed in the Pākehā world and its definition of success.

“I’m constantly surprised at the direction my life has taken,” she says. “I was brought up disconnected from my Māori side, discouraged from learning te reo and taught that following any path other than the Pākehā one would lead to stress.”

So she did what was she was told, gaining a law degree and spending a year travelling through Asia, Africa, the US and Europe.

In New York, Michele landed an internship at the United Nations, working for the Coalition for the International Criminal Court. For a young lawyer, it was a coveted position.

Back in Auckland, she worked for a law firm for a decade before having her first child. As her maternity leave came to an end, Michele realised she didn’t want to go back to the conservative legal world, one where she had to account for very minute of her time. “It’s not a way for a human being to live.”

Instead, she tapped into her desire to reconnect with her cultural roots, studying rongoā and foraging for native plants the way her ancestors did. When a kawakawa balm she’d made to treat daughter Eva’s painful eczema proved successful, word soon spread.

“One day I was in a yoga class and overhead women talking about a miracle native balm. I remember thinking, ‘Damn someone has already turned it into a business.’ But it was actually my balm they were talking about.”

That led to Frankie Apothecary, a business that specialises in natural skincare products based on rongoā principles. Michele sold the business in 2019 to focus on AWWA.

But then, as now, her focus is on helping women, a focus that’s driven her from a young age.

She’s particularly interested in working with indigenous women to help redefine their periods.

“So many nations have been heavily colonised and indigenous people have lost connection with their ancestry, history and culture. Periods were sacred for so many of our ancestors, where they returned their blood to the earth. AWWA isn’t a profit-led company, but is driven by a desire to decolonise our bodies and periods and for women, especially indigenous women, to reconnect with nature and their menstrual cycles.”

How we advertise

Fifty years ago “period” was a dirty word and advertising feminine products was kept as vague as possible, usually involving girls riding horses and, bizarrely, blue liquid being poured onto pads. Brands were restricted in what they could say on air, including not being able to make any reference to absorbency, cleanliness, anatomy, comfort, insertion, application, duration or efficacy, so no specific information could be included.

It wasn’t until 1985 that the word “period” was used in a TV ad, by none other than a pre-Friends Courteney Cox. An ad for Tampax saw the actress decked out in spandex, telling viewers, “Feeling cleaner is more comfortable. It can actually change the way you feel about your period.”

Thankfully, the times they are a changin’ and advertising standards have evolved so that makers of menstrual products no longer have to hide behind a shroud of secrecy. Although in 2020, Australian period-poof underwear brand Modibodi found itself in the eye of an advertising storm when Facebook claimed showing period blood violated its guidelines, which block “shocking, sensational, disrespectful or excessively violent content”.

The same thing happened when AWWA made a realistic ad featuring real menstrual blood in 2021. Maybe we still have a way to go.

Period products available here

Menstrual cups: These are soft, medical-grade silicone or rubber cups that are inserted into the vagina to catch the blood flow. Simply empty the cup every eight to 12 hours, rinse it and put it back in. Kiwi brands include The Hello Cup, HannahCup, Wā Collective and Coralcone.

Reusable pads: As the name suggests, these are cloth pads you can wash and reuse. They’re usually made of absorbent material such as cotton or bamboo and have a snap button on the wings to secure around your underwear. It’s estimated that one reuseable pad can replace up to 120 disposable pads. Local brands to look out for include Lunette, Aku washable pads and HannahPad.