A neighbour gave Amahle the courage to break free from her abusive husband. She shares her story with Fiona Fraser.

The scars aren’t all visible, but they’re there. Amahle* lives with post-traumatic stress disorder, back pain, insomnia and tinnitus. She doesn’t cope well in crowds, is nervous to walk the streets around her home, and fears the day her former husband returns to New Zealand, finds her and potentially kills her.

Amahle is one of the more than 35% of women in Aotearoa who experience violence at the hands of the person they love, and hers is a particularly chilling tale – one she’s courageously sharing to highlight the incredible work Women’s Refuge does.

“They save women’s lives,” she says, simply. “And I am one of those women.”

To tell Amahle’s story, we need to go back to South Africa where the now 50-year-old was a single mum. Raising her four-year-old son alone, she says she was considered something of an outcast, a woman of colour in a country still grappling with racial equality. Frowned upon by her community, meeting a tall and successful man like Samuel* was a godsend.

“I was the black sheep of the family,” Amahle begins. “And when he began to talk to me online, he was just so respectful and kind.”

Feelings blossomed between the pair and they decided to wed. Amahle confides that for her, Samuel – an educated, well-spoken, white South African – presented “a way out”.

“He was the solution to the problem of my being an unmarried mother,” she says.

For the first two years of their marriage, their relationship was peaceful. “But soon he began to insult me, and the controlling behaviour began. I had no say in anything. He made every decision, right down to the clothes I wore and what I put in the shopping trolley. Once, when I tried to choose some diced chicken, that enraged him so much he pushed me and my son out of the car, in the dark, on the side of the road.”

Physical intimidation happened gradually, Amahle says. “He’d start by pulling my ear, smacking me on the side of my head,” she recalls. Then she fell pregnant, and the hitting stopped. “I had three children with him, and he wouldn’t touch me while I was carrying his children – wouldn’t touch me while each of the children were babies. Those were the best years of my life, being pregnant with my kids.”

He wouldn’t touch me while I was carrying his children. Those were the best years of my life, being pregnant

As the children grew, the beatings became regular – and increasingly violent. Amahle says any little thing could provoke Samuel, so she learned to remain silent and stay out of his way. It was only then, she says, that she could rely on a beating just once a week, instead of every day.

“On more than one occasion, he broke my ribs. And if the hiding was intense like that, he’d go out and buy me jewellery afterwards – rings, bracelets. The more violent the beating, the more expensive the gifts.”

He was sadistic, too. “He owned a gun, and one day he shot the family dog in front of me and my six-year-old son, and left him there to suffer. It was absolutely heartbreaking, and I knew he was showing me the extent of what he could do to me.”

Amahle says there was no one to reach out to – no one who could help. “At that time there weren’t any good support services in South Africa for women experiencing violence. I tried to tell my mum, who lived 17 hours away, what was going on – not so much about the hitting, but about the control and the anger. And she said, ‘You know, everyone has problems. Be grateful. At least you have a big house, nice cars and a good life.’”

But that, too, was about to change. One evening, while away on a business trip in Dubai, Samuel sent an email announcing the family was moving to New Zealand. No warning, no discussion. It was a decision that would further isolate Amahle from her already small network of friends and family.

On arrival, the couple settled in Napier and Samuel bought a produce business, in which Amahle also worked. Samuel would disappear, sometimes for a week at a time (Amahle later found out he’d met a woman in Tauranga), but when he was home, life was miserable. The beatings were intense, Amahle says. “It was as if being here brought out the worst in him. He would sidle up to me holding a knife, threatening me constantly,” she recalls, shuddering. “He started beating the children, banging their heads together. He wanted to scare us all. It got so bad I became convinced he would kill my eldest son – so I put him on a plane back to South Africa, to save his life.”

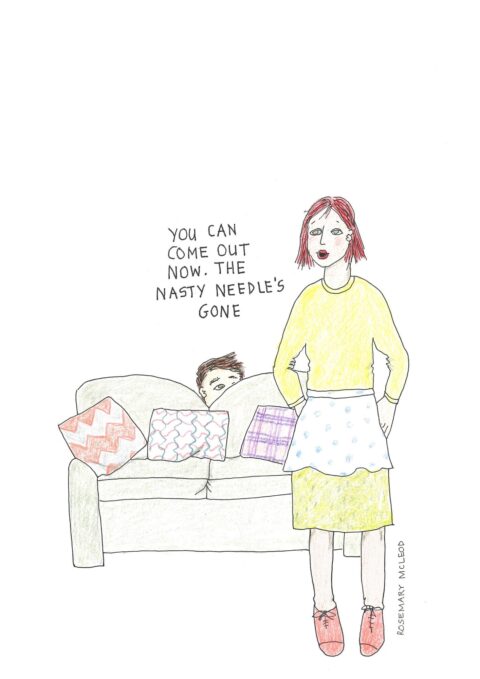

Amahle was home alone one day when her neighbour popped in. “She’d been hearing a lot of screaming, she said, and fighting. She’d waited for a day when his car wasn’t there and chosen her moment. She said she didn’t want to interfere – and to please tell her to go away if I didn’t want to talk. But then she asked me three little words: ‘Are you OK?’ I told her everything.”

The actions of that neighbour sparked a chain of events that very likely saved Amahle from death at the hands of her husband.

First, Amahle and her neighbour formulated an escape plan. “She got two stools from her house and told me to bring the children out to our back yard. She showed us that there was a stool on her side of the fence and a stool on my side and how they could jump over the fence to get away. I packed an emergency bag that she hid on her property, and she showed us how she would leave a window open for us to get in if we ever needed to. Then, I got the children a small mobile phone, and we put her number in it. We gave them a password – if they ever text her the word, she would come straight away. And she encouraged me to call the Napier Women’s Refuge.”

Amahle hadn’t ever heard of Women’s Refuge before, but she nervously made the call. Terrified her husband would find out what she was up to, she was at pains to tell the Refuge staff member who answered how sensitive this was, how frightening Samuel could be.

“I thought I’d sound neurotic, but these were the experts – and she had heard it all before. She was so calm, so helpful, took down my story, arranged to notify Child, Youth and Family [now Oranga Tamariki], and organised for a social worker to visit at a time Samuel definitely wouldn’t be home.”

I thought I’d sound neurotic, but these were the experts – and she had heard it all before

With the support of Women’s Refuge, Amahle’s two school-age children were collected from class to attend their Tamariki programme, and delivered back again before the bell rang so Samuel would never know. “They learned that what was happening was not their fault, that their father’s behaviour was not OK, and what they could do if they were threatened. It really helped them feel safe and secure.”

Amahle – who, as a migrant, was reliant on Samuel’s residency to remain in New Zealand – had assumed she was powerless and could never leave her husband. Women’s Refuge assured her that her safety came first, and residency could come later.

“I also did their women’s education programme ‘Journey to Freedom’, and it was so good I went five times! It taught me to formalise a safety plan and gave me the confidence that one day I could leave him.”

But at home, she was “walking on eggshells. I knew if he had any inkling we had asked for help, he would fly into a rage. And he would certainly kill me.”

In the end, it was the skills taught by Women’s Refuge that saved Amahle. One day, while working together in their small business, Samuel did his best to end her life. Grabbing her by the hair, then the throat, he threw her to the floor. With one foot on her head, he used his other steel-capped workboot to kick her in the skull and body, over and over again.

“I remembered how in one of the Refuge courses I’d been taught that if you just covered your head and played dead, he would grow bored. They’d taught me to practise holding my breath too. So I lay still and I stopped my breathing. And when he gave up kicking me, I just ran – I ran next door to a charity shop. I couldn’t talk from the strangling, but I wrote a note that said, ‘Call police. My husband tried to kill me.’”

Samuel was found, arrested and appeared in court facing charges of assault. But Amahle says, to her horror, he was released on bail, leaving her and the children more vulnerable than ever.

“I was disgusted. Women’s Refuge were right there with me though. They sorted the protection order, found me a new place to live and got me a lawyer. They wrapped me up in care and love.”

Amahle says the police officers assigned to her case were also a huge ally at a dangerous time.

“For two weeks, they were always at my house – just parked outside, or stopping by. Because, you know, he was watching me. He would just turn up and sit outside the house. It was the most terrifying time of my life,” she says, shaking her head.

Although he was convicted and ordered to complete community service – which is a crime in itself, Amahle believes – Samuel was able to withdraw all the family’s money and escape to South Africa without serving a day of his sentence. “He left me destitute. He emailed me from the airport to say, ‘Good luck, bitch. See how you survive with all that debt. I’ll come back for you.’”

That was in 2014. In the intervening years, Amahle has slowly rebuilt her life, sometimes working three jobs to get by. She’s taken more courses through Women’s Refuge to more fully understand the impact Samuel’s abuse has had, she’s completed the pre-entry year for a social work qualification, and is enjoying watching her children grow, safe from their father’s violence. For now.

Amahle says even though he was convicted of a crime, back in South Africa it’s easy to simply buy a new name, a new passport, a whole new identity. Samuel’s already sent messages to Amahle using a different email address – an unyielding reminder of the hold he has had over most of her adult life. “I’ve learned to control my fear,” she says. “I’ve done a lot of work on that, but there are times I still feel very scared. Like now.”

Baking and art are her outlets. “I’m a Good Bitch,” she says, hooting with laughter, referring to the regular baking she does for charity Good Bitches Baking (GBB). Her artwork is also important to her. She donated several pieces to Women’s Refuge and a designed a T-shirt design for GBB in support of the Christchurch mosque attack victims. “How amazing is that!” she says with a grin.

PHOTO BY FLORENCE CHARVIN

Life is far from easy for Amahle, but it’s a darn sight better than it was when she was constantly bloodied, bruised and bewildered, she says. Now, the grandmother of two just wants to speak up – shout her story, if necessary, in the hope it will help others. And she wants to meet someone new. “It’s time.”

No matter what’s next for Amahle, her incredible legacy will be her four beautiful children, who are alive to tell the tale of their mother’s survival.

They have a loving neighbour and the Napier Women’s Refuge to thank for that.

And their mother’s courage.

They’re here for you

Julie Hart from Napier and Hastings Women’s Refuge says Amahle’s story is typical of many migrant women’s experience.

“The women we come in contact with who’ve come here from a range of overseas countries, frequently find themselves with no residential status and tough immigration rules that make them totally reliant on their abusive partner to remain here. Some are also shunned by their own communities if they express a desire to leave their husband or partner. It’s very difficult for them.”

Women’s Refuge whānau support advocates, however, can work closely (and in complete confidence) with migrant women to help them stay in their homes safely, or leave their partner successfully. “We never tell women what to do,” Julie says. “We ask them what they want to do and then help them achieve it.”

Services might include training to support safer interactions at home, installing monitored alarms or security systems, and programmes for children living in a domestic violence situation to better understand and interpret their emotions and responses to violence.

Safe houses are also available for those who need to flee and have few options. “On average, a woman will leave her abusive partner seven times before she leaves for good. And each time they go, they get a little bit stronger, a little more empowered.”

Her message for women experiencing abuse of any kind is to tell someone. “A friend, a family member, a GP, work colleague or neighbour. Seek help, and if at first you don’t get the response you need, keep reaching out until you do. Of course, if you’re in immediate danger, please call 111. And there’s also our free helpline for advice and instant support, 24 hours a day, which is 0800 REFUGE. We will listen, we will help, we promise that.”