Singer, mother, mentor and woman on a mission, Hinewehi Mohi has dedicated her life to her craft and to helping others. She shares her journey with Siena Yates.

It should have been one of the proudest moments of a young singer’s life and career, but when Hinewehi Mohi represented New Zealand in a world-first performance, it crushed her. It was 1999 at London’s Twickenham Stadium, and it was the Rugby World Cup – 75,000 people were watching in the stands, and many thousands more on TV screens at home.

Hinewehi was the first person to sing the New Zealand national anthem in te reo Māori at a significant event like that, and she was proud and excited to represent her culture and Māoritanga on the international stage. It was beautiful, and many of us welcomed and embraced this enchanting new version. But some people were not so impressed, and what followed was a “harrowing” onslaught of racist backlash that totally blindsided the singer, now 56.

It “completely burst her bubble”, so much so that it’s a mamae (pain) she still carries more than 20 years on, partly because before then, that bubble she’d been living in was a fairly idyllic one. Now a world famous singer, songwriter, TV producer and reo Māori advocate, Hinewehi grew up in Hawke’s Bay and started learning te reo Māori when she was just 10, under the guidance of her father, Michael Mohi.

She went to St Joseph’s Māori Girls’ College and later, to the University of Waikato where she took Māori Studies with some of the legends of the reo Māori world. Even when she started travelling and spent some time in London, she still found a community of mainly Kiwis and Aussies so, she says, “I was essentially in my little bubble, even in England. I was kind of sheltered my whole life.”

She’d had a few bad experiences, often to do with her name and the colour of her skin. “I was given this name Hinewehi at a time when giving your kids a Māori name was not fashionable. It was really kind of random in the mid-1960s to give this fair-skinned baby a Māori name, so people would say things like, ‘What are you, white girl, doing with a name like Hinewehi?’”

She was also aware of her father’s struggle with language trauma; the reason he started teaching her and her siblings the reo as kids was because he was just starting to learn himself. “His parents could speak Māori growing up, but were discouraged – physically – from doing so; it was that thing about being strapped for speaking Māori, and I’ve spoken with kaumātua who physically had their mouths washed out with soap.

Dad and his siblings didn’t have any language around them at all because [my grandparents] didn’t want their children to be punished too. So it was, ‘Get on with the English-speaking world and all that it takes to do well there”, and that’s a really common story. So many people have experienced that loss and it is a real trauma,” says Hinewehi.

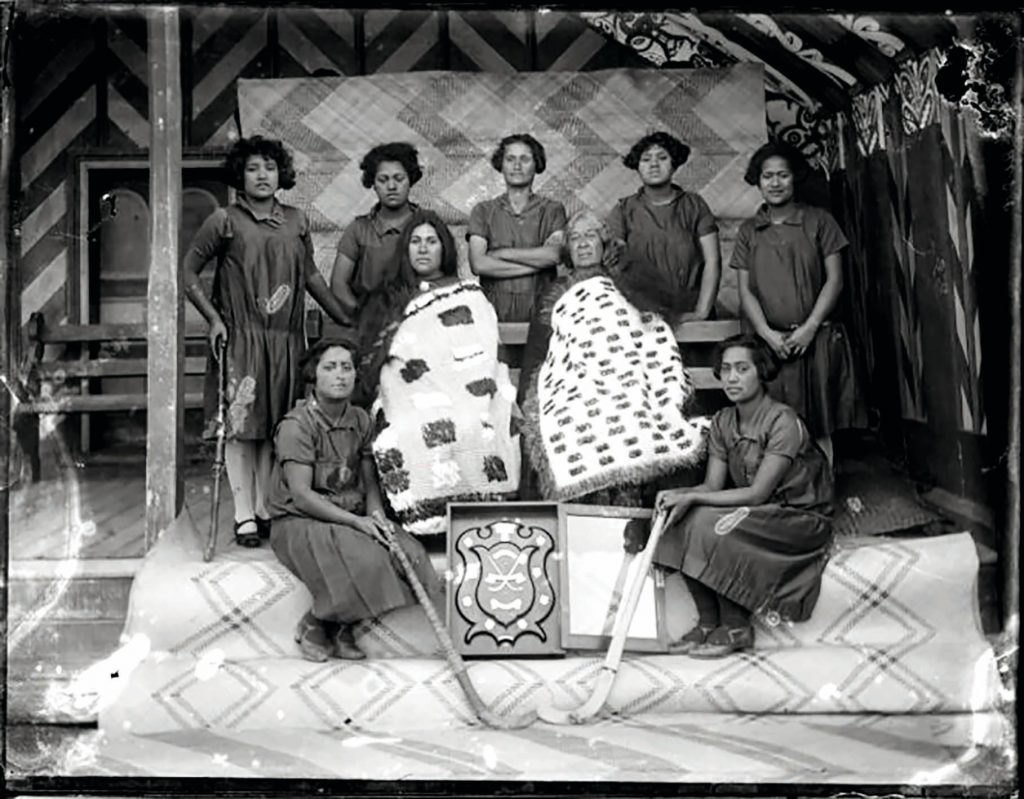

PHOTO SUPPLIED

She was spared that fate. Her father giving her the reo and the understanding of her Māoritanga that he never had meant Hinewehi was able to grow up “feeling really centered”.

“Otherwise, you sort of feel like you’re just floating above the ground, rather than being centered into yourself and mindful of your surroundings and connected. I had a real sense of pride for representing where I’d come from, and then I went to Waikato University and had tutors talk about the importance of having the confidence to be who you are in your own skin. It’s difficult to articulate what it means to me, but I couldn’t exist in any other way.”

And it’s something she’s been determined to pass on to her own blended whānau. She and her husband George Bradfield have five adult children and five mokopuna. She adores her whānau, but apologetically confesses to being “one of those annoying, busy nannies who they see only fleetingly”.

It was the birth of Hineraukatauri 25 years ago that changed her life in the most significant of ways. Born with severe cerebral palsy, Hineraukatauri requires round-the-clock care and is confined to a wheelchair. Her journey has brought huge challenges, of course, but it’s also enriched the life of everyone around her, says her devoted mother.

“She’s an absolutely extraordinary human being. She has inspired me and my family so much, and so many other people too, with her grace and serenity. She has a very beautiful way of reaching out through her silence that’s very powerful and when people meet her, they get an immediate understanding of her and the challenges that she has with her life, but also an immediate appreciation for their own existence.”

Hineraukatauri was also the inspiration behind Hinewehi’s groundbreaking Raukatauri Music Therapy Centre, an amazing organisation that’s become a haven for children and adults living with a wide range of disabilities, using music as a powerful form of healing.

“It’s a place where miracles happen,” Hinewehi says with pride. The only one of its kind in Aotearoa, there’s no doubt the centre has had an incredible impact on thousands of people living with disabilities and their families, but Hinewehi is quick to deflect any praise. “Nōku te whiwhi – the pleasure is all mine,” she says, explaining that both her daughter and the music therapy centre have given her far more than what she’s put in. “I can’t possibly describe my gratitude for what we can do for others. It’s a wonderful thing to have the opportunity.”

I can’t possibly describe my gratitude for what we can do for others. It’s a wonderful thing to have the opportunity.

It’s 10 years now since Hinewehi underwent treatment for breast cancer, but the experience has been on her mind recently since Labour MP Kiritapu Allan went public with her cervical cancer battle. Like Hinewehi did back then, Kiri has bravely shared her journey in the hope it will encourage others, particularly wāhine Māori, to have screening tests.

Describing health inequity for Māori women as a “big, complicated mess”, Hinewehi says, “We need to work really hard to make it a priority. We need to address these very negative statistics.”

She’s been hugely buoyed by reports of increased cervical screening rates since Kiri’s revelation, and Hinewehi recalls that when she was diagnosed, many of her friends and whānau were prompted to have mammograms, which led to several discovering they too had cancer. “It’s about breaking down all kinds of barriers and encouraging women to put their fears or embarrassment or whatever it is to one side, because it really can save lives.”

While her own treatment was successful, Hinewehi admits the fear of cancer returning is never too far away. “If you have little aches and pains you immediately worry, because you do have a heightened risk of the cancer returning. But that’s why it’s so important to keep on top of any issues and to seek help – that applies to everything really, whether it’s physical, emotional or psychological issues.”

Determined to help others in any way she can, Hinewehi is also supporting people on their te ao Māori journeys and through whatever trauma they may have. Most recently, that’s included the likes of Bic Runga and Tiki Taane, who were just two of the many artists Hinewehi helped to translate their songs into te reo Māori for the Waiata / Anthems album in 2019, and the Waiata / Anthems series, which is now streaming on TVNZ OnDemand.

“Bic and Tiki were particularly affected because their parents had the reo, but it was the same situation [of parents not passing it on to protect their children]. So for them to then be liberated by an opportunity to sing in their heritage language is something so special. I’m overwhelmed by people’s sense of empowerment from it,” says Hinewehi, who describes the act of helping others into te reo as “the gift that keeps on giving”.

That’s why she produced the first Waiata / Anthems album and it’s why she returned to make the TV series, even though she was already stretched pretty thin. The album was released in September 2019 and TVNZ approached Hinewehi about the show the following month, at a time where she was “still in recovery” from the ordeal of the album.

“It was really exhausting, I probably underestimated how much of a journey I was going on with each of the recording artists. I underestimated how emotional that would be, supporting them through that. But also physically, travelling to Auckland from Hawke’s Bay, it was a lot. So I was still just coming out from under my duvet,” recalls Hinewehi.

Ever since Waiata / Anthems, Hinewehi’s been working in her role with APRA AMCOS (an Australasian copyright organisation) as Pītau-whakarewa (Māori Membership Growth and Development Leader), in a bid to create a bilingual music industry. The Waiata / Anthems TV show offered an opportunity to bring that vision one step closer because this time it wasn’t just releasing an album, it was telling the stories behind the artists’ reo journeys, delving into the history of the language, the trauma of the Māori artists, the fear and education of the Pākehā artists, and the power of te reo Māori.

“To see those stories of why artists would want to do it and to hear them articulate how important it is to them is amazingly powerful,” says Hinewehi. “It may not be perfect to start with, but to see someone make that start, take those brave first steps and be so empowered by the process, it blows my mind every time.

“It’s such a beautiful thing because it shows a real desire from people to want to make a true and valuable connection, and I think most people want to know where they come from, to be reassured about their sense of place and connection to the land. So when they get that first experience and support to record a song of theirs in Māori, the transformation of that person… nothing beats it.”

I think most people want to know where they come from, to be reassured about their sense of place and connection to the land.

Bic Runga’s episode is particularly hard-hitting, as she gives a raw and emotional kōrero about growing up Māori-Chinese in Christchurch, and the racism and disconnect she’s dealt with. “It’s really hard to watch it without shedding a tear,” Hinewehi says. “Seeing her from the person I met two years ago to now – wow. She’s an incredible person and an incredible talent; a national treasure. For her to tell that powerful story is mind blowing.”

She also recalls seeing Bic in concert recently and witnessing the pop star introduce her song as “Haere Mai Rā”, rather than just “the Māori version of ‘Sway’”. “That was so beautiful and authentic. It wasn’t putting a spotlight on, ‘This Photos: Florence Charvin. Hair & make-up: Makayla June. is me singing in te reo Māori’. It was, ‘This is just me, expressing me’. That was even more powerful because she was just wanting to represent her true self, and she could, and she did.

If you’re supported to grow and flourish as a human being, it is really a beautiful process

“If you’re supported to grow and flourish as a human being, it is really a beautiful process and when it comes to identity and your sense of self – where you came from, who you’ve come from, your sense of place and connection to it, and who you want to be – it’s a full circle of completion. Sometimes you get a bit wobbly. But essentially, it’s something Aotearoa feels like it wants to embrace.”

That’s particularly true now with Covid-19 changing the world forever. Hinewehi truly believes it’s been an opportunity to connect with ourselves as Kiwis and realise what really sets us apart.

“With lockdown, it was an opportunity to be introspective and I think, now more than ever, everyone is just feeling like we’re particularly special and we’ve got something really special to say and to show the world. They’ve already noticed that Aotearoa is special and music is a wonderful way of getting out everywhere, especially while we’ve got exclusive dibs on being able to have concerts at Eden Park with 50,000 people, you know? It just feels like we’re ready now, like Aotearoa has come of age and really wants to be different rather than trying to be like a little Britain or little America.”

Helping not only artists, but the music industry as a whole, to embrace te reo Māori as one of the biggest things that makes us special as a nation is what has always driven Hinewehi. It’s why she sang “E Ihowā Atua” at Twickenham 22 years ago and it’s why she’s dedicating her mahi towards helping the next generations of history makers on their way.

“I’ve always loved performing in Māori, especially being asked to sing by Tourism New Zealand around the world. I loved it and really felt that I was in a privileged position where I was given an opportunity to express myself in that way and get the response that I did.

“But now I’ve got to a point where I’ve started helping emerging artists wanting to come through singing in Māori, and wanting to actually perform myself less and less. I would much rather just make room for someone young and beautiful coming through who has something new to share, because then it’s evolving, it’s growing,” she says.

And the end goal?

It’s surprisingly simple: acceptance. To take a nation that once turned on her for singing her reo on the world stage, and turn it into a nation which knows no different.

“What you would ultimately want to hear is someone saying, ‘Why is that a big deal?’ And I think anyone probably under 30 would already be thinking that sometimes, but that’s what we’re aiming for – that it’s not a big deal, it’s really normal and we’re all enriched by it.”