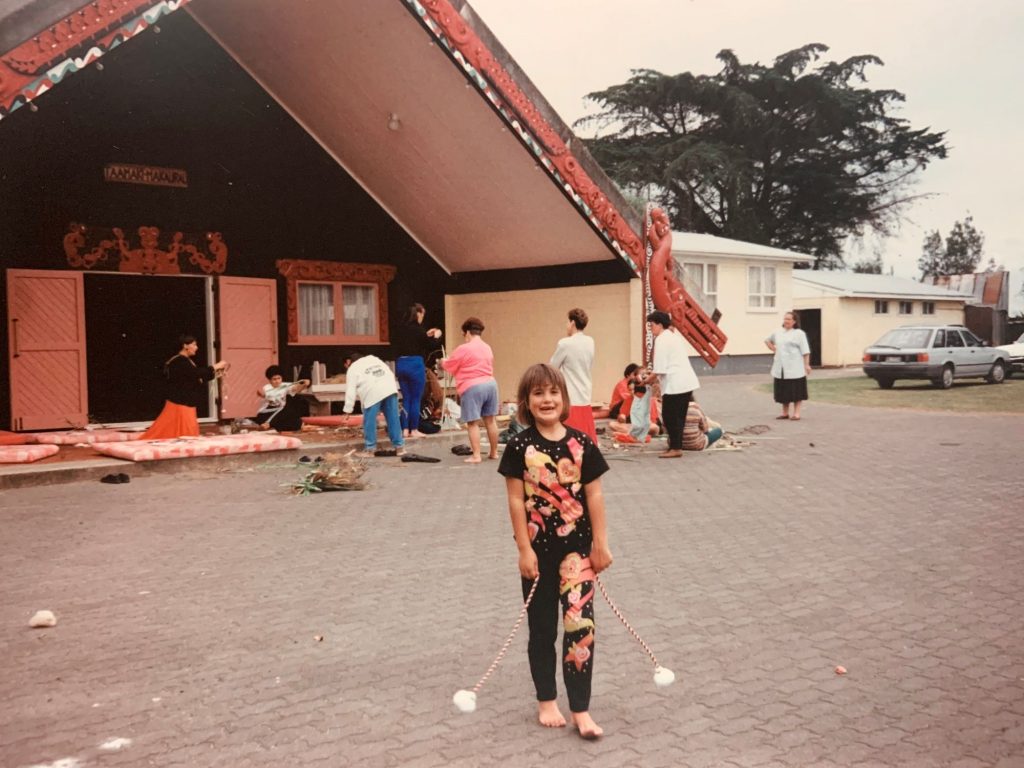

Activist, multimedia maven and mother Qiane Matata-Sipu has been working for her marae and community since she was a child. Siena Yates learns that she’s not about to stop.

There couldn’t have been a worse day to visit Qiane Matata-Sipu.

She’s been on and off the phone non-stop since before she even got out of bed. People have been knocking on her door relentlessly – media, whānau, neighbourhood kids, more media.

Her daughter woke up with an eye-roll, quickly realising māmā would have to work that morning. “She’s three and she’s just like, ‘I’m over your life already, Mum,’” Qiane laughs.

When she greets me at her home, it’s with a thousand apologies; “it’s crazy this morning”.

It just so happens that the day Woman decided to visit was the day Cabinet was meeting to discuss a potential resolution for Ihumātao – Qiane’s papakāinga (ancestral home) and the whenua (land) she and her cousins Pania Newton, Bobbi-Jo Pihema, Waimarie McFarlane, Moana Waa and Haki Wilson (with whom she formed the SOUL campaign group) have been fighting to protect from a housing development for the last five years.

The land was set to have 480 houses built on it by Fletcher Building, but in 2016, tangata whenua and their supporters occupied the land at Ihumātao in a form of protest which escalated to the national #ProtectIhumātao movement when Fletcher issued an eviction notice in 2019.

Qiane (pronounced key-ah-nee), a journalist and former editor, is the group’s point person for all things media today, so we barely manage to sit down before the phone rings again. She takes it, apologetically. Three minutes later it rings again. This time she really has to take it – it’s Kingi Tūheitia (the Māori monarch).

Oddly, it’s kind of perfect; neither of us could’ve dreamed up a more accurate representation of Qiane’s life.

As well as working with SOUL (Save Our Unique Landscape) at Ihumātao and raising a young child with her husband Willie Sipu, 35-year-old Qiane also has her own media and photography business, Qiane & Co, and runs Nuku Women, a multimedia platform dedicated to telling the stories of indigenous women.

Only one of those jobs earns her any income, the rest is for love and passion.

Qiane was born and raised at Ihumātao and, while her mother was a strong presence, as the eldest mokopuna she lived mostly with her grandparents, who were community leaders and taught her all about te ao Māori and mātauranga Māori. As such, Qiane’s been working for her community and marae since she was a child.

PHOTO SUPPLIED

That, she says, is just a “reflection of being an indigenous wahine…it’s one of those things that you’re born into, always working toward supporting the collective.”

That’s not to say Qiane hasn’t also been career-driven. She simply focused on career and collective at the same time.

She went through all her schooling in Māngere, becoming co-head girl and dux at high school. She studied journalism at AUT and got her first “real job” right out of uni at 21, writing for Mana magazine – her very first story landed the cover and she won a Qantas Media Award in her first year of reporting. She was then poached by Spasifik magazine, where she became deputy editor at just 25.

During this time, she was also freelancing on the side for Te Puni Kōkiri (the Ministry of Māori Development) and working on her documentary, photography and arts career, including putting on some exhibitions with Creative New Zealand.

But after three years, Qiane realised she needed “some tino rangatiratanga over my life” and left Spasifik to start Qiane & Co, taking on communications, commercial photography and journalism work, branching out into family portraits and wedding photography to generate more income.

She’s now eight years into her business and has never really had to advertise to get work in any of her fields.

“That’s come from f***ing hard work and sacrifice,” she says. “ I’ve put in hours upon hours to build the reputation I have in the industry now. People know they can trust me and they’re going to get something good. It’s grown really slowly. But, you know, it means that I’ve obviously done something right.”

It’s a success story, to be sure. But it hasn’t by any means been an easy road.

Perhaps Qiane’s most well-known venture is Nuku Women, an online collection of in-depth interviews and stunning portraiture with indigenous women sharing their stories, which she hopes to turn into a book this year.

But while Nuku has raised a following of thousands, involved celebrities like Kanoa Lloyd, Kiri Nathan and Chelsea Winstanley, and counts reo Māori icon, broadcaster and Woman columnist Stacey Morrison as a member on its advisory board, it was also born out of the darkest time in Qiane’s life.

It started 10 years ago, when her grandfather, Joe “Jumby” Matata, passed away unexpectedly after suffering a heart attack at home.

PHOTO SUPPLIED

For the first time during our interview, her smile fades as she tears up at the memory – and it’s little wonder.

“I had to give him CPR and… basically, he died in my arms. It was one of the most traumatic experiences of my life, hearing my nan scream out to me. He’d just gone really stiff on the couch,” she recalls quietly.

When she continues, it’s with tears streaming down her face – mine too – because what comes next is one of the most heartbreaking things I’ve ever heard.

“People talk about the achievements I’ve had in my life and I always say, ‘Oh yeah, I can do anything’ – but the one thing I couldn’t do was save him,” she says, wiping tears from her cheek.

“I held on to that for so long. Like, ‘Why can you do all these f***ing things but you couldn’t do the one thing that you actually needed to do?’”

Qiane’s nan Dawn died four years ago, and as if that grief wasn’t enough, all the pain from her grandfather’s passing came flooding back too – especially because she never got to say goodbye to her grandmother. By the time she got the call and got to the hospital, there was “just an empty room with an empty bed”.

“I’ve never responded to someone dying in the way that I did that day. You know when you see it on TV, when people really grieve at the hospital? My body was doing that. I had no control over it.

“A whole chunk of my world had ended because that was the last of my grandparents – everything that I knew about my life was tied to those two people. So her dying was just a whole end of everything that my life had been to that point, and I didn’t know who I was anymore. I really didn’t know how to be. The foundation of my world was gone.”

On top of all of that grief, Qiane and Willie had been struggling with infertility for years due to her polycystic ovarian syndrome and didn’t qualify for free treatment because her BMI was “too high” (she says, with a roll of her eyes).

And her grief compounded to the point where, for a solid two years, Qiane “was absolutely broken, all day, every day and I just carried around this heavy blackness”.

“To go through finding so many alternatives and undergoing IUI procedures and literally standing right here [she points to the space by her sliding door] and being told, ‘Your treatment was unsuccessful’, and just the grief that comes with that.

“And, you know, growing up with cousins who are on their fifth child because they just looked at their boyfriend. And being wahine Māori, wahine Pasifika with no children, with a husband who has 10 brothers – there’s all of these things that come with that.”

Eventually, the couple decided to bite the bullet and come up with the money for IVF. After about five months of preparing both her body and their bank account, “miraculously, we fell pregnant”. It was a girl.

Haeata te Kapua Sipu was born at 38 weeks on a super moon and was named after her grandmother and great grandmother; a name which also comes from a phrase which translates to “the beam of light that broke through the clouds”. She was “meant to be”.

PHOTO SUPPLIED

It was when Qiane fell pregnant that she came up with the idea of Nuku, after she started thinking about what she wanted to teach her daughter.

“There was a lot of grief released in her birth, which allowed for space for other things to come into my world and other ideas to come into my mind,” Qiane explains. “She very much was a healer in my life and she also untapped this other level of creativity in me.

“I was very conscious that I wanted to create something for her. And when I say ‘for her’, she represents all of the indigenous women of her generation. I wanted to show these women, as well as ourselves, what indigenous female success is and that it’s not one thing.”

I wanted to show these women, as well as ourselves, what indigenous female success is and that it’s not one thing

Nuku launched in January 2019 and, so far, Qiane has collected 58 stories – 54 of which are currently published.

It is so much of a personal success to Qiane that she says she “had twins”: her baby and Nuku.

“I do it because I have to, because I love the kaupapa. I do it for the people that message me and say, ‘I’m learning from this’, or, ‘I listen to this with my daughters,’” she tells. “Nuku started as a project, but it’s grown into a movement. It is so fulfilling.”

But it’s also a lot of work – especially on top of running your own business, raising a child and being at the helm of a history-making land reclamation movement.

As phone call after phone call comes through, Qiane seems more and more weary with each one. Eventually, I have to ask again (for real this time, despite how important and fulfilling all this mahi is): “Aren’t you tired?”

She sighs. “I am completely exhausted. Like, I am so mentally and emotionally exhausted. But if I don’t do the mahi, then I’m not working towards the outcome that I need for my whānau. You just can’t not do it. You’re called to do it. Your tūpuna are telling you to do it.”

I get that. But I also know one cannot pour from an empty cup, and I say as much to Qiane, who sighs again.

“I just don’t know how to just switch off,” she admits. “I actually don’t know how to do that and it genuinely concerns me, because I’ve become very addicted to the pace of my life and it’s not healthy and I don’t think it’s fair to my whānau. I often think about what kind of mum I am and what kind of wife and daughter I am when I’m constantly doing everything all the time.”

But this is the thing: Qiane’s work isn’t just work. It’s part of her.

“I don’t know what my life would be like if I did [take a break]. Probably, if I’m scared of anything, I’m scared of that,” she says. “I attribute my identity to all of these things, so what happens if one of these things goes, you know? I don’t know how to be if I’m not all of these things.”

While that may seem like a woeful lack of boundaries – and she concedes that sometimes it is – when your mahi is as much a part of you as Qiane’s is, you don’t want to cut yourself off from it.

She has to make money to feed her daughter, yes, but more than that – she has to create art and tell stories to feed her soul. She has to do whatever it takes to protect her whenua, because it’s the whenua on which she and generations before her grew up, where she held her dying grandfather in her arms, built a home with the love of her life and welcomed the daughter she fought for years to have.

“My self-care will come when it comes and I know that’s not the way we’re supposed to live or whatever, but I don’t care because I’ve got too much to lose,” says Qiane. “If I’m capable, then I should do it, you know? You don’t grow these skills and get this experience for nothing.”

“Until I know that the things that I’m directly involved in are safe – particularly Ihumātao – I won’t stop. When I know that we won’t lose something because I’ve stopped, then I’ll rest.”

PHOTO BY EMILY CHALK