New Zealand Police’s Keeping Ourselves Safe programme for schools has come a long way since its inception in 1987, most significantly in taking the message away from “stranger danger” to empowering children against real life threats closer to home. In light of the recent Children’s Commissioner shake-up, Michelle Robinson asks whether the programme is hitting the mark, and what more can be done to protect our tamariki when we can’t be there.

Mum, where are the dry towels?”

What an odd thing to call, I remember thinking as I sat on the class mat, watching a video as part of the New Zealand Police and the Ministry of Education’s Keeping Ourselves Safe initiative.

It was 1995, I was eight years old, and the video showed a girl fending off a kiss from a man who had followed her to the bathroom under the pretense of visiting her parents.

The clip was memorable. Why would a grown man try to kiss a young girl? And what exactly about that was not okay?

“Most young children (below the age of seven) have difficulty understanding that a ‘good’ person could give them a ‘bad’ or ‘confusing’ touch,” Massey University researchers noted at the time.

Sadly, New Zealand has one of the worst rates of child abuse in the developed world, with 14,000 substantiated incidents reported each year. A rate which will have only increased during the Covid-19 lockdowns.

As many as 250,000 children were found to have been abused in state care and mental health and disability facilities between 1950 and 1999.

Around the time that I took part in the programme, there was an alleged flasher at our local beach reserve. I recall hearing how he beckoned my little sister from the bushes while we were playing on the playground after school. The police later showed up to interview her.

I don’t know if anyone was arrested or whether the sunburnt middle-aged man with a beer belly and no obvious pants was an apparition. A foregone conclusion in the mind of a six-year-old, trying to make sense of the foreboding messages she was hearing in school.

Thinking back to the flasher on the beach, my sister and I were well-versed in what actions to take if a stranger approached us while we were out, but were less prepared for what to do about someone closer to home.

“Understanding that sometimes it is okay to say ‘no’ to an adult, that not all secrets need to be kept, that people known to the child might be abusive, and the difference between good and bad touches, are difficult concepts to comprehend,” researchers into Keeping Ourselves Safe’s earlier versions summarised.

First there were the uncomfortable bear hugs around my developing chest. Then the unwanted kisses on the back of my neck that wearing my hair up unwittingly elicited.

Even confidence gained in my newly acquired self-defence skills were undone by a “Yeah, but look what I can do, you can’t get out of this one” disempowering straddle across the floor.

One day these “minor” abuses of power culminated in a greater breach of trust during an after-school sports massage.

It was awkward. The door was closed. I was encouraged to strip down to my underwear. I was 15.

“Whoops. I shouldn’t do that, that’s naughty,” was the only explanation or excuse for an apology I received.

I didn’t expect it, it didn’t make sense. I didn’t want to cause a scene. I was embarrassed. It baffled me how someone tasked to look after me could be so inappropriate.

“Some children created their own stories in an effort to make sense out of the information provided without compromising their strong need to view parents and caregivers as safe people,” the Massey University school of psychology study on Keeping Ourselves Safe stated.

“Even the older children, while aware of the possibility that familiar people may be unsafe, expressed a strong belief this could only happen in other people’s families.”

Stranger danger

The police have steered away from the concept of “stranger danger” since the late 1980s. Most abuse towards young people is inflicted by a well-known or trusted adult. In 90 percent of cases involving the sexual abuse of girls, the perpetrator was known to the victim.

“‘Stranger danger’ makes it easier for abusers known to the child (the most common source by far of abuse in New Zealand), because children think that people known to them aren’t ‘strangers’ and therefore won’t harm them,” a statement from the New Zealand Police says.

“Rather than concentrating on stereotypical strangers, it is important children know about the behaviours to avoid and report, no matter whether they come from a person unknown or familiar to the child.”

Keeping secrets

Fast forward 30 years and my children now have Keeping Ourselves Safe as part of their primary school health and safety curriculum.

My children were at their friends’ house recently; their mother is a good friend of mine. When my son arrived home talking about “secrets” downstairs, it still raised alarm bells.

Trying to get the “secret” out of him was like pulling teeth. He was embarrassed to tell me about an innocent game between himself and his friend, afraid of my reaction, because he knows what is and isn’t appropriate play. I was concerned that someone might have come over and said or done something to take advantage of my young son.

“It was further found that the majority of children were aware that sexual abuse usually involves touching but most lacked a clear understanding of what kind of touch this may involve,” researchers at Massey University said. “The belief that a ‘bad’ touch always feels uncomfortable or makes you feel bad inside was found to be misleading.”

In this case the “secret” was an innocent game between two young friends. But it highlighted the need for me to empower my children for when I can’t be with them.

My children and I were at a family event recently, the kids converging together in play. At bedtime my son confided that a bigger kid had pushed him over outside, and again in the toilets. Here I was thinking we were in a safe place, and that my older son knew what to do in an unsafe situation.

Perhaps we never truly know who is and is not a safe person for our tamariki. The only people we can trust are our kids. They are phenomenal judges of character.

Keeping Ourselves Safe was updated in 2020 to be more inclusive of gender diversity. The core messages of safe and unsafe touching, awareness of body parts, and the importance of speaking up when uncomfortable, have been maintained.

The curriculum has caught up, and we need to too.

We can warn our tamariki about unwanted touching, about keeping themselves safe, but bodily autonomy is arguably the best component of protection here.

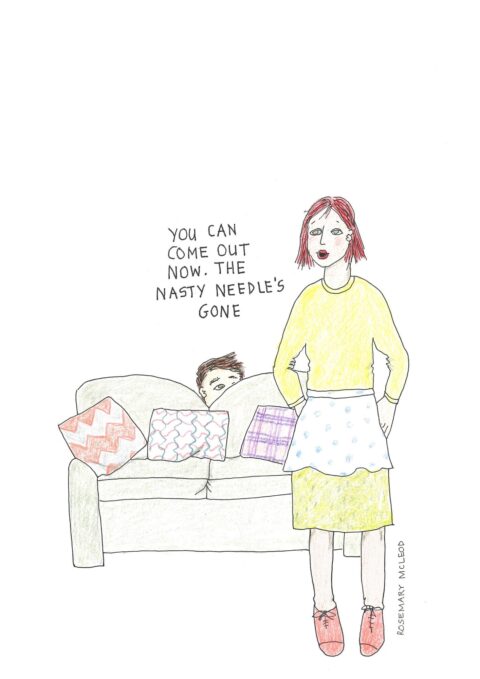

Examples of a lack of bodily autonomy broached in the updated Keeping Ourselves Safe programme range from a grandmother demanding a kiss to a friend’s older cousin putting his hands down a younger child’s pants.

Sexual abuse is usually coercive, deceptive and builds up over time.

Commentary from the recent Royal Commission inquiry into the abuse of children in state care highlighted a “lack of cultural intelligence and values”. A casual response to victims and their complaints was also highlighted by the continued employment of a person accused of abuse in a child-facing role by Oranga Tamaraki until very recently.

Running adjacent to news stories from the inquiry was an investigation into a music teacher accused of sexual abuse of his students. What stood out to readers was the casual manner with which the victims were treated, both by their abuser and the authorities responsible for protecting the victims.

In the latter, the victims were met with a “it’s your word against his” response from police at the time, who have since apologised.

Only within the last decade have we really started to see reports of sexual violence taken at a victim’s word. This is largely attributed to the #MeToo and #Time’sUp movements, following on from the publicity from the Harvey Weinstein scandal, and reports on the Stanford University campus rape.

Education equals prevention

The casualness with which abuse occurs is astounding. The lack of empowerment for the victim to seek help, the “what ifs” that hold them back from coming forward, the fear of making others feel uncomfortable or “making a scene” that stops them from speaking up.

Two people kissing before penetration suddenly occurs without request or consent. An abuse of power by a teacher towards a student, or a male towards an intoxicated and/or comatose female. The mere phrase “that’s naughty” to excuse abuse, the memory of which cannot be as easily absolved. A careless touch which lasts minutes or even seconds but leaves the emotional imprint of a lifetime.

Our best means of prevention are to teach our kids from the get-go that their bodies deserve to be respected and their voices deserve to be heard.

If we shove, grab, smack or coerce our tamariki into an activity they are not keen on, or we put adults in high importance above them, then they learn to be submissive.

This means they might put a question mark over any incident where they are touched or commanded to do something they are uncomfortable with. This has so many implications in how our kids go on to manage peer pressure as adolescents, as well as how they navigate potential abuse scenarios.

It goes without saying that we too need to instill responsibility and care into our boys.

The Keeping Ourselves Safe programme’s most recent addition for high school students, Loves Me Not, now specifically tackles conversations around healthy relationships and consent.

We also need to take great consideration over who we invite into our inner circle of trusted adults. To carefully consider who we allow the privilege of babysitting or having unsupervised time with our precious tamariki.

It all comes down to trust and respect. From a tender age. From the moment our babies are born. When we respond quickly to their cries, when we allow closeness of touch to comfort and soothe our pepi, we teach them that we care about how they feel. When we listen to our children’s chatter and linger without judgement so our teens know they can safely confide in us, we are teaching them their opinions, preferences and voices are heard.

My children are old enough for sleepovers and playdates. They attend childcare and school. They are away from me a great deal. The situations they encounter are, to a degree, out of my control.

What is within my control is the ability to raise them to be confident in their bodies and voices. It’s far from being the only response to the threat of “casual” sexual abuse, but is a vital link in the chain of prevention.