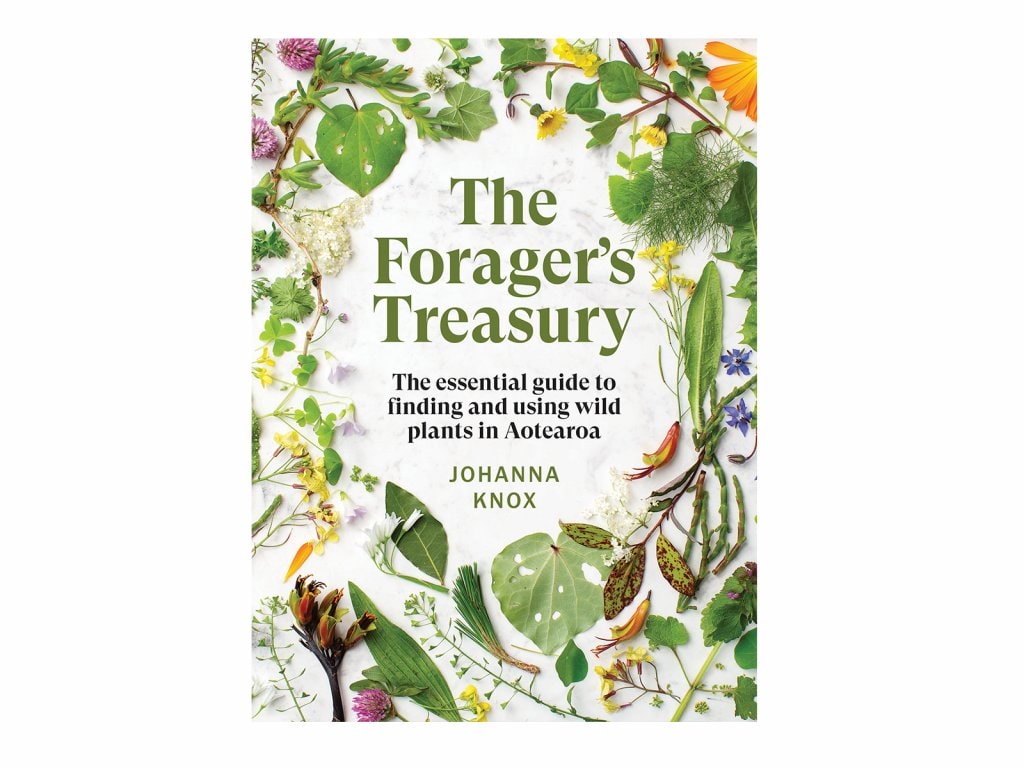

Kiwi forager Johanna Knox says there’s an abundance of food waiting to be discovered in both urban and rural wildernesses – you just need to know what to look for.

I think we’re all foragers at heart. From birth, the drive kicks in. We snuffle around, smelling, feeling and able to see only as far we need to, to find food in our tiny caregiver-sized domains. Months pass, then years, but we still employ all our senses in the hunt for health and sustenance. Gathering speaks to many needs at once: to escape, to explore, to discover, to collect, to heal, and to provide for ourselves and our loved ones. Most of all though, I believe it speaks to our need to connect to the world around us.

As a forager, you’re in a unique position to discover the effects of terroir on the plants that grow in your patch. A quick stroll can reveal, for example, that the lavender flowers growing outside a local café have a strength and softness to their fragrance that’s quite different to those growing beside a neighbour’s gate, which may have a quieter scent with a sour note.

Before beginning your foraging journey, familiarise yourself with the relevant guidelines and legislation. Be careful to forage away from areas of pollution and avoid areas that have been sprayed with herbicides or pesticides – if you’re unsure where these are, contact your local council to check.

Treasures to forage for

Mānuka and kānuka

It’s easy to confuse mānuka with its relative kānuka, but kānuka has noticeably softer leaves. It also generally grows larger than mānuka, lives longer and has smaller flowers – white only – that tend to grow in clusters. Mānuka is the go-to source of woodchips or sawdust for smoking

meat, fish, cheese, chocolate and more.

Mānuka leaves make a delicious flavouring for both savoury and sweet dishes – use slim branches to infuse the cooking liquid, then remove them as you would rosemary. Alternatively, dry the leaves and powder them to use like any other dried herb. Kānuka generally has a more harshly medicinal flavour and aroma. Try young, new leaves, stripped from their branches and finely chopped, in any recipe where you’d normally use thyme, lavender or mānuka.

Clover

The petals have sweet nectar at their base, and can be pulled apart and sprinkled into salads or onto biscuits, cakes and desserts as a garnish. The leaves are quite edible, too, although most people are underwhelmed by that thought. Where they grow lushly, red clover flowers have a gorgeous honeyed fragrance, but this doesn’t last long after picking. Clovers are also highly valued by some for the oestrogenic isoflavones they contain, and are said to help with troublesome symptoms of menopause. Many over-the-counter treatments contain red clover extracts, but some people swear by a simple tisane of the flowers, taken daily (it’s pleasant and mild in flavour).

Ice plant

Ice plants sprawl in mats across beaches around the country. The fig marigold is a large yellow ice plant with thick, finger-like leaves that are three-sided in cross-section. It’s an invasive pest from South Africa that overruns native plants and changes the structure of sand dunes. Our native ice plant, horokaka (pictured above), needs to be cherished. It has smaller pink flowers and its leaves are smoothly curved like tapering tubes, rather than three-sided. Succulent ice plant leaves are harshly tannic and only barely edible raw, but they can be sliced and pickled. Pound the leaves up to release the juice and use it neat or in vinegars or tisanes. Applied externally, the juice soothes and protects grazed, irritated or inflamed skin.

PHOTOS BY LUKE HARVEY AND JOHANNA KNOX