As a year of upheaval draws to a close, a global quest for a vaccine has delivered hopeful news. Sarah Catherall looks at what we can expect in 2021 and beyond.

It’s the hot dinner-party topic: when will we get a Covid-19 vaccine in New Zealand, how long will it protect us before the immunity runs out, and when will life return to near-normality?

A vaccine has been dangled as the only solution to the global pandemic that by late November had taken more than 1.4 million lives, and infected more than 60 million people. Right now, about 300 vaccines registered with the World Health Organization are being developed by drug companies around the globe, and several have announced successful early results.

As parts of Europe went into pre-Christmas lockdown, there were promising signs that some New Zealanders might be vaccinated early next year, and all of those who line up for a jab will be vaccinated by mid-2022.

The government has signed a deal to buy 1.5 million Covid-19 vaccines – enough for 750,000 people – from Pfizer/BioNTech. It also has an agreement to buy up to five million vaccines from Janssen Pharmaceutic – owned by Johnson & Johnson – starting from the third quarter of next year, in what would be a single-dose inoculation. Both deals are subject to the vaccines successfully completing clinical trials and getting the Medsafe tick.

According to Research, Science and Innovation Minister Megan Woods, New Zealand has “a portfolio approach’’, which will allow us to access a range of vaccines. The Ministry of Health is working out who would be vaccinated first, considering three issues: those at risk of contracting the virus, those at risk of spreading it, and those at risk of dying or becoming severely ill from it.

Calling the shots

Both the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine and a vaccine by United States biotech company Moderna have been shown to have a 95 percent success rate. The two drugmakers have moved at record speed to seek regulatory clearance for emergency use from the US Federal Drug Agency.

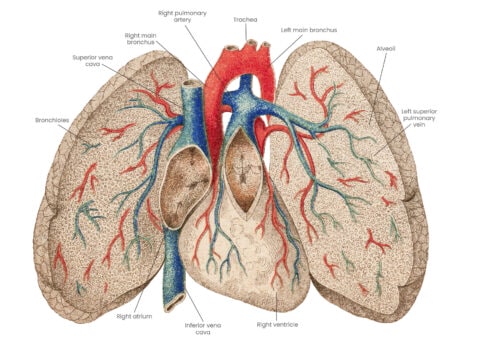

The vaccines use a new technology called synthetic messenger RNA to activate the immune system against the virus. The Pfizer one is more complicated to store and needs to be kept at -70°C. Both require two doses to be effective.

(As Thrive went to press, Oxford University, working with AstraZeneca, announced it had developed a successful two-shot vaccine that can be stored at fridge temperature, with an overall effectiveness of 70.4 percent.)

The Janssen vaccine is more like a traditional vaccine, so it’s easier to administer, able to be used in a broader population, including in the Pacific Islands, and can be stored at 4°C for up to three months.

“It is a different technology too, so that spreads the risk,” says James Ussher, the science director of the government-funded Vaccine Alliance Aotearoa New Zealand (VAANZ) and an associate professor at Otago University. “Janssen is a reputable vaccine manufacturer with a history of bringing products to the market.’’

As is the case with the flu jab, we won’t all get the same drug. Those most at risk of catching the virus – border control staff, maritime and airline workers, and laboratory scientists – are likely to be offered the earlier Pfizer doses. “We are unlikely to get the doses all at once, as well,’’ James says, adding that healthcare workers, the elderly and the immune-compromised should be next in line.

The Ministry of Health is preparing for a range of vaccine scenarios and will finalise the vaccination approach once it knows what is available. While the vaccine scene is changing almost daily, the current vaccination timetable is about right, James says.

He says about 60 percent of New Zealanders will need to be vaccinated when the borders reopen, to avoid a Covid-19 outbreak. “It will depend upon the efficacy of the vaccines and whether they protect against infection or make people less infectious. The studies to date are assessing whether they protect against symptomatic disease, which is subtly different.”

The New Zealand quest

Another question is how long immunity lasts, which is still not known – some vaccines might provide longer coverage, and it’s still unclear if innoculation will stop a vaccinated person spreading the virus anyway.

Given the promising vaccines on the horizon, Christchurch-based vaccine expert Dr Fran Priddy describes the developments as “a shot in the arm’’ for ending the pandemic. Based at Wellington’s Malaghan Institute of Medical Research, she is the clinical director of VAANZ and is working with New Zealand scientists in the hunt for a vaccine.

Three local vaccines are in the pipeline: a recombinant spike protein vaccine being developed in Dr Davide Comoletti’s lab at Victoria University of Wellington, an inactivated virus vaccine in progress at Professor Miguel Quiñones-Mateu’s lab at the University of Otago, and a pan-coronavirus vaccine being explored by Wellington’s Avalia Immunotherapies, which is working alongside international collaborators.

The potential local vaccines haven’t yet gone through clinical trials. They’re unlikely to be used to fight the current pandemic, but are being developed for future anticipated coronoviruses and to ensure vaccine supply in the future.

Fran says there are populations that need to be tested in Pfizer and Moderna’s next clinical trials. Pzifer’s vaccine hasn’t yet been trialled on children under 12 and pregnant women, for example.

The Janssen vaccine is a good one to cover a broad population, she says. It uses the same technology as an Ebola vaccine also made by the pharma company, which has been approved for use by European regulators.

‘It’s better to wait’

While the vaccines may be administered for emergency use in countries with a high number of cases and outbreaks – and Australian officials have declared they hope to get their entire population vaccinated next year – Fran says New Zealand can afford to wait for further safety follow-ups. “The risk here is vaccinating huge numbers of healthy people. You want to take very little risk. It’s not like giving people chemotherapy to fight cancer. In a country like New Zealand, where the main risk at the moment is an economic one, it’s better to wait.’’

She imagines that when global travel resumes, people will initially need to carry evidence proving they’ve been vaccinated, similar to the way yellow fever is treated today. “But it might get to be like the flu over time, where we don’t require people to be vaccinated for the flu when they travel.’’

Fran expects New Zealand’s timetable might be brought forward if we buy three or four vaccines. However, she says vaccines won’t solve the pandemic overnight. “There are the complexities of delivering the vaccine, what percentage of people can be vaccinated (it’s rarely 100 percent) and how long immunity will last.”

For those nervous about getting any vaccine when it arrives, she says it will be safe if approved by regulators. “I’ll be lining up for one as soon as it’s available here.’’

However, for those thinking vaccines will wipe out Covid-19, experts say the virus is likely to stay in the world long term, becoming part of our viral pool. Although we will develop more immunity over time, James Ussher issues a caution: “This virus is likely to be endemic in the population, circulating indefinitely.’’