Renowned ceramicist Elena Renker mixes pottery with gardening at her peaceful property near Auckland’s Long Bay.

Every surface in Elena Renker’s pottery shed is lined with her creations, in various stages of completion. They occupy the wooden shelves, the white windowsills and even the exposed framework of the walls, and each is meaningful. “You get to know your pots so well, they become your friends,” Elena says. “I get really attached to them because I know I’m never going make a pot like that again.”

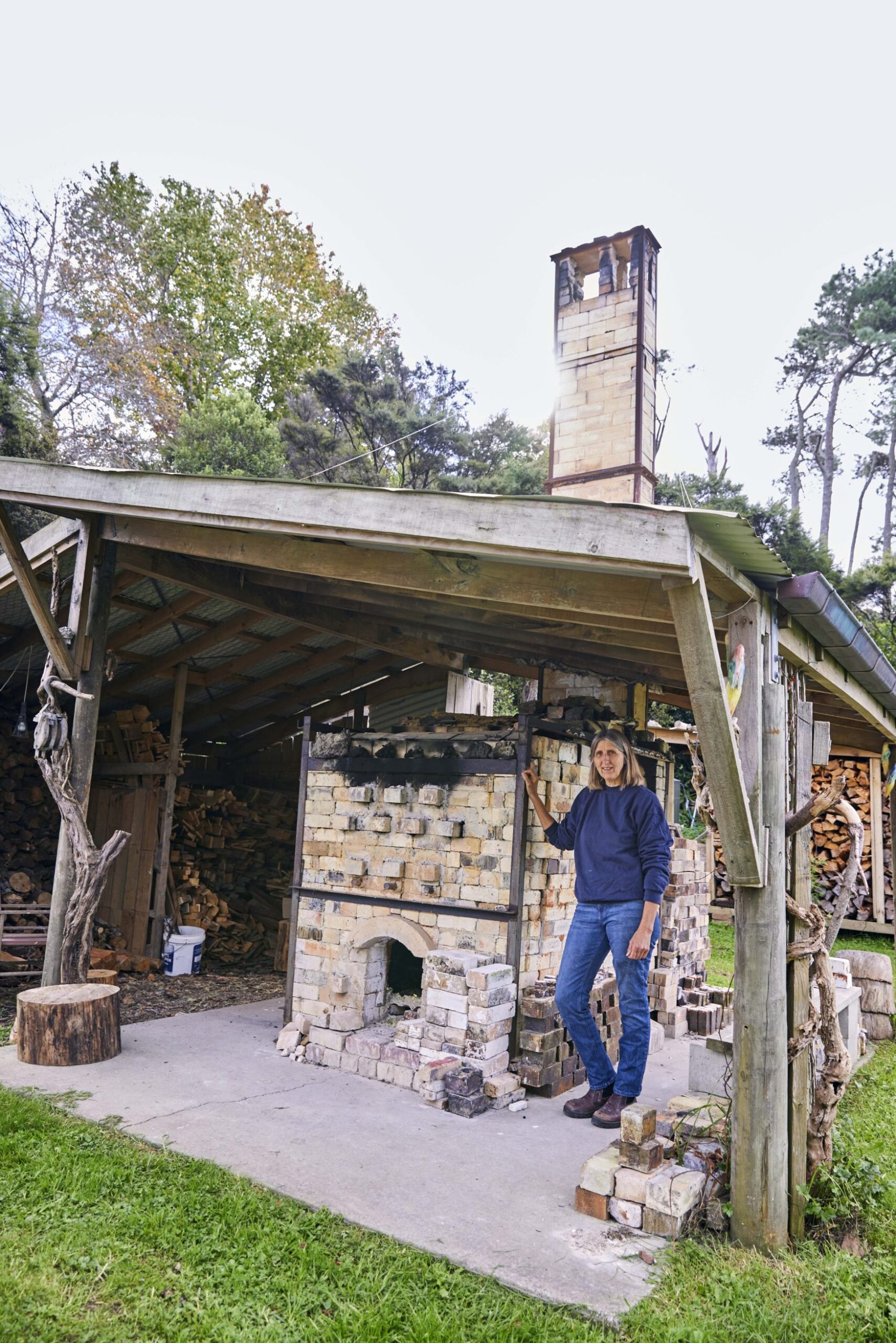

Elena moved to the lifestyle property near Long Bay, at the northern tip of Auckland’s North Shore, in 1986. From the large corner window of her shed, she looks along her sprawling, self-seeding vegetable garden to her wood-fired kiln with its large chimney.

In the distance is a row of old pines – as the branches die off, she collects them and then dries them for two years to use in the kiln.

Having since bought the neighbouring section, she now has room on the property for not just her own house but also homes for her adult children – who have returned at various stages with their partners and children – and a family of dogs. As we sit by her pottery wheel to chat, canines Mika and Hanna – a grandmother and granddaughter – wander in and out.

It’s a peaceful, inspiring setting, which makes for a creative environment. “I think it’s more what comes out of you rather than what you see,” says Elena. “You’re constantly thinking and exploring ideas.”

Elena grew up in a creative household in Cologne, Germany. “My mother was very much into crafting and my father was a collector, so there was a lot of art around. Even as a child, I always made things.”

At 17, she stayed in Pondicherry, India, with friends of her parents, and decided the best use of her idle time and hands was the nearby Golden Bridge Pottery. She was given a ball of clay, shown an old kick wheel under a mango tree and told to go for it. She spent three months there but isn’t sure she finished a single pot. “Naturally, it took me a long time to get anything together,” she said. “But I did like the process.”

On returning to Germany, she embarked on a year of structured learning and working at a studio in southern Bavaria. Between wedging clay, mixing glazes and cleaning the studio, she would make as many pots as she could – and cut most of them in half. “For the first six months, we had to cut every pot to see the evenness of the walls and whether it was thin enough.”

She went on to study graphic design in Munich, before having the first of her five children and emigrating to Aotearoa. It wasn’t until her youngest started school, in 1998, that her hands were free to start pottery again, and she began taking classes with Auckland Studio Potters. “It was nearly 25 years later I went back on the wheel, and it was like riding a bike,” she says. “A bit wobbly, but I still knew what to do.”

She did a ceramic arts diploma at Otago Polytechnic via distance learning, and honed her craft with leading Kiwi potters. In a postgraduate year, she focused on recreating the traditional Japanese shino glaze, which she says never exits the kiln quite as expected. It’s now her signature.

On completion of her studies, Elena was invited to represent New Zealand at the Mungyeong Traditional Tea Bowl Festival in South Korea, to which she returned four years in a row to connect with and learn from the international community.

This is where she learnt about the art of tea bowls. An auspicious item, the tea bowl is a meeting of sculpture and function on an intimate scale, and the hand of the maker is felt and appreciated during the tea ceremony.

“You can be completely free making a tea bowl as long as you stick with the few requirements,” says Elena, who also makes more modern tea bowls that can be held in one hand for today’s breakfast rituals of reading the paper or checking our phones.

“Making a beautiful object that people use – that for me is the most important thing.” Elena’s routine is to arrive at the pottery in the morning and spend the day switching between her work and the garden – her fork, shovel and axe are propped up by the back door. Both activities are about working with the earth, she says. “I think it’s a really good combination. You have to centre the clay on the wheel before you can start working. And centring the clay means you’re centring yourself. So the garden is really important for me, not just for the food, but also for my own frame of mind.”

Lately, the varying availability of materials, not to mention Covid-19 logistics, have been forcing Elena and other Kiwi potters to rethink their glazes and clays. “We’re struggling,” she says. “But then it’s also good because it kind of forces you to change, and it forces you to keep trying other things.”

While pottery is seen as a calming pastime for enthusiasts, it’s an intense process for a professional with upcoming exhibitions. From the origin of the minerals found in each clay to the weather on the day of firing, many factors influence what Elena ultimately sees when she opens the kiln door. But it’s this temperamental process that inspires her, and the imperfect features that make her works come alive.

“I love the unexpectedness. I love the wood-firing process because I can make the pots and I can glaze them, but the fire, and the ash that lands on them, play a huge role.”

To fire her pots, Elena’s kiln must reach 1300 degrees. “It’s a matter of looking at the flame, listening to the kiln,” she says. “Every time you stoke when it’s at the high temperature, it roars, and you can feel it. It almost vibrates with the pressure of the flame.”

The heating process can take a tense 20 hours. “If you stop, you lose everything, so you just keep going. It doesn’t matter how tired you are. You don’t have any choice.”

While her work gives her an immense sense of satisfaction, the gratification is rarely instant. “The main reaction when unloading the kiln is disappointment,” she says. “You have a certain idea of how you want it to look, and they almost never look that way.”

Elena will put everything on a table and then walk away, sometimes taking weeks to decide which pots are complete and which need re-firing. Although a colourful piece may catch her eye, it’s often the quieter pot sitting beside it that is the best, a revelation that may only come once it’s sat on the table for a while.

Once a year, Elena hosts an open studio – the one time she’ll wash all the windows, dust away the cobwebs and display her pots properly. The crowd grows every year. She’s also recently held solo shows in Auckland and Christchurch, and is currently working up to a show in the United States. Her personal career highlights include the first of her three Premier Awards from Auckland Studio Potters, and a prize at the Waiclay National Ceramic Awards in 2019.

She’s still close to many of the people she’s met on her journey, and even returned to the pottery in Pondicherry 40 years after her first throw to lead a workshop.

Although she hopes to travel again soon, for now she is enjoying the slower pace, with time to truly experiment. “I’m quite happy just pottering around,” she says.