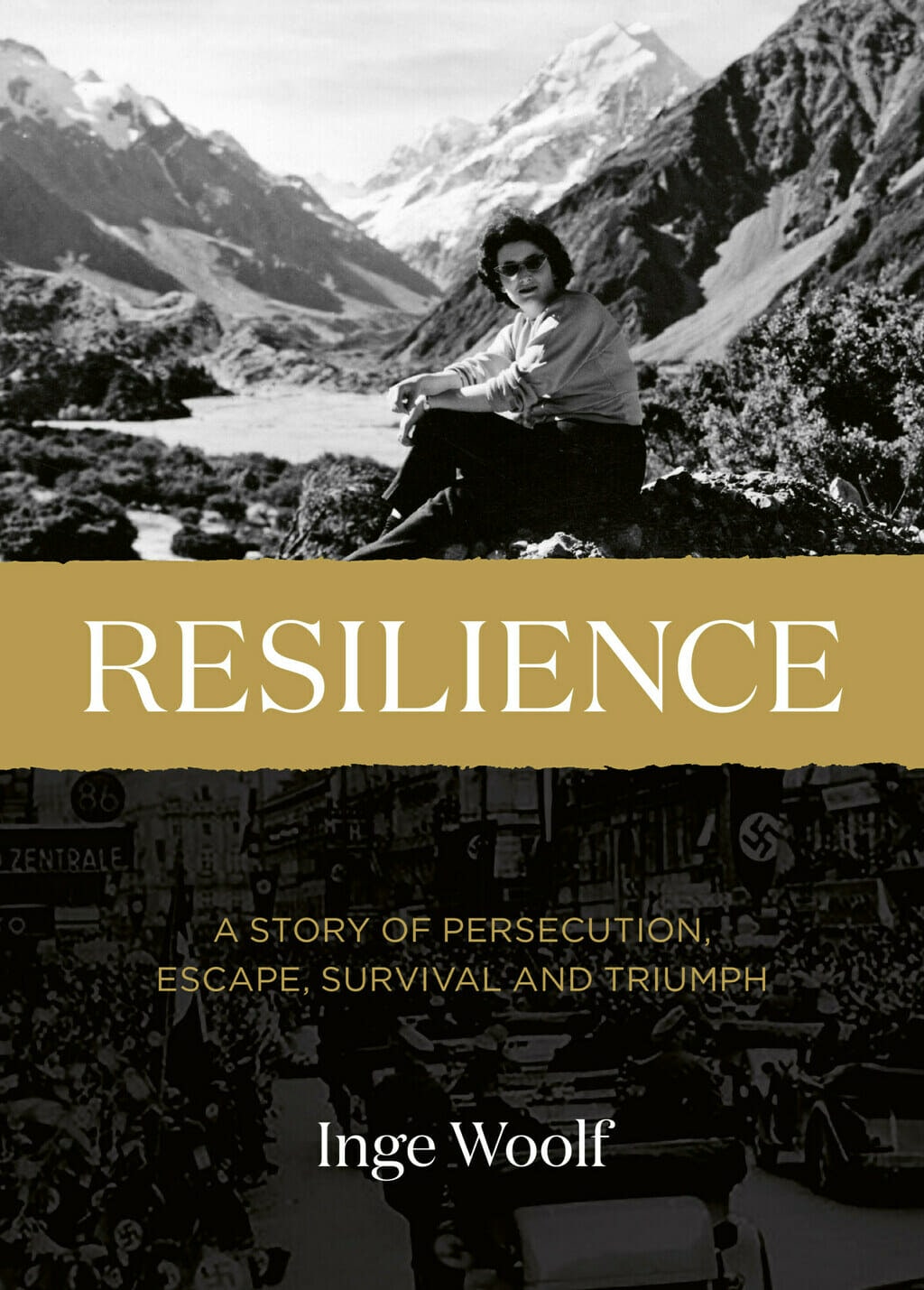

Getting to know your mother can take a lifetime but for lawyer turned consultant Deb Hart who completed her mother’s memoir after a diagnosis of terminal cancer it has meant a lifetime and then some. Inge Wolf had begun writing her extraordinary life story when a terminal diagnosis meant she ran out of time and her daughter Deb stepped up to finish it.

The gripping story which involves a family fleeing Nazi Germany is published this week. Resilience: A Story of Persecution, Escape, Survival and Triumph by Inge Woolf is a riveting story of a life begun in the shadow of Nazi Germany and ending on the other side of the world in Aotearoa. On the eve of publication we caught up with Inge’s daughter Deb Hart about the remarkable journey she’s been on and the legacy her mother left. Read the exclusive extract below the interview. Full article here

Pragmatism was obviously crucial to ensuring our best chance of escape. My parents decided to convert to Christianity. It had become clear that things were getting dire for Jews, and a Lutheran church in Myjava, near to my father’s birthplace of Krajné, was converting Jews to try to save their lives, giving them papers that said they were Lutheran.

On 27 April 1938 I knelt between my parents in that dark church and was baptised. My parents bought me a small gold cross to wear after we converted. They never discussed that day. It must have been a tough decision to convert, even though we were not religious.

Much later, here in New Zealand, long after we had come back to our Jewish roots, my mother was amazed when I told her I remembered the conversion. My brother Johnny, born after the war, was even more amazed when he discovered a record of the conversion at the church. He had travelled to Slovakia with some old papers my mother had given him to search out what had happened to our family, and found that the trail led to that church. He didn’t know how to break the news to me and was very relieved when I told him I knew but had never wanted to upset our mother by talking about something she obviously did not want to have revealed to the family.

We had little money, having lost everything when we left Vienna, but my parents set out to give me some fun in Prague. My mother’s brothers had also escaped. Karl had made his way to Palestine before Hitler arrived in Vienna. I don’t know their exact escape route, but Paul and Teddy escaped largely on foot, trekking by night to avoid being captured and slipping through the border. Teddy’s fiancée, my aunt Bertl, who was Polish and had no current passport, was still in Vienna. She could not cross the border with us, and I suspect the trek Paul and Teddy had taken was too difficult for her. My parents hatched a plan. It was perilous to return to Vienna, with escalating antisemitism and increasing restrictions being brought against the Jewish population there, and it was illegal to use someone else’s passport. But Bertl looked a little like my mother, with the same dark colouring. The Nazis had a warped idea of what Jews looked like, an ugly caricature of an often stooped, hook-nosed, olive-skinned person with dark eyes and a sly look. My father was the opposite of this image – he was tall and thin, had fair skin and blue eyes. And he had a Czech passport. So Daddy returned to Vienna and, using my mother’s passport, he and his future sister-in-law Bertl posed as husband and wife and crossed the border into Czechoslovakia, a trip that was filled with danger. And that was how Bertl joined my parents and me, Paul and Teddy in Prague for Christmas of 1938…..

…. Our flight to freedom left from Berlin. Imagine the decision to travel to the heart of Nazi Germany with a small four-year-old. It was a bold journey and as such I guess my parents thought that they were unlikely to arouse suspicions. After all, who would expect three Jews to willingly travel to Berlin? On the last day we would be able to use our passports, we set off on the first leg of our trip – a train journey from Prague to Berlin.

The train was full of military personnel. I remember seeing them all dressed in their different uniforms. We were the only civilians in the carriage, carrying just a bag each, as if we were tourists. We wore our finest clothes, as you did when you travelled in those days. My mother had on a smart hat, jauntily tilted to one side. I was wearing my best travelling outfit and the small gold cross on a delicate chain that my parents had bought me to complete the picture. But I know now that should some authority have scrutinised our papers, recent conversion to Christianity would not have saved us.

My parents told me to be a very good girl, to lie down and try to sleep, because they did not want any attention to be drawn to us. It must have been a terrifying journey for them and, although they tried to maintain a brave front, that fear was transferred to me as I lay down on the seat, trying to get to sleep, and watching the last snow of winter still clinging to the embank- ments flashing by as the train sped through the night. Mummy later told me that ‘our hearts were in our boots’. I was scared too and do not remember arriving in Berlin.

My next memory is being on the plane, destined for Croydon in England. We were above the clouds. I thought we must be in heaven and I was on the lookout for God and the angels hiding among all that billowing white fluffy stuff. It was quite a disappointment that they didn’t appear.

Like something out of a suspense movie trying to maintain the anticipation, the plane couldn’t land at Croydon Airport as there was fog over the runway. In a terrifying turn of events, we flew back across the English Channel and landed in Amsterdam. The airline put us up for the night in the best hotel, the Amstel. It was full of affluent guests . . . and three Jewish refugees escaping Hitler. For my parents it was a harrowing night. They ordered room service. I remember the fish supper being served on a silver salver covered by a silver cloche to keep it warm. In the eyes of a four- year-old, not used to such opulence, it was very impressive. The excitement for me was only marred when a fishbone got stuck in my throat, and I coughed and coughed and made myself sick – and brought up the bone.

The next day we boarded the plane again and this time made it to England, on 29 March 1939. We were so lucky. We arrived at a time when tensions were mounting and suspicions abounded regarding those arriving from continental Europe. Not only did we manage to escape the Nazis, as by then they were in Czechoslovakia, but we entered the United Kingdom just before harsher immigration rules instituted on 1 April 1939 required all Czech visitors to have a new kind of visa. We were also given refugee status, something not afforded to all of the hundreds of refugees arriving that week at Croyden airport.

Two days after arriving, my family had found support from the British Committee for Refugees and then the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia. Documented in their records is the following narrative: ‘Mr Ponger came to this country to save his life. He is a Jew. The immigration officer let him in, because he was compassionate with their people.’ It was only later that I comprehended the kindness and power held by the immigration officer who allowed us refuge