Vanessa Wedding made history in 1969 as the first New Zealander to undergo gender affirming surgery. She talks to Aroha Awarau about her place in history and finally feeling complete.

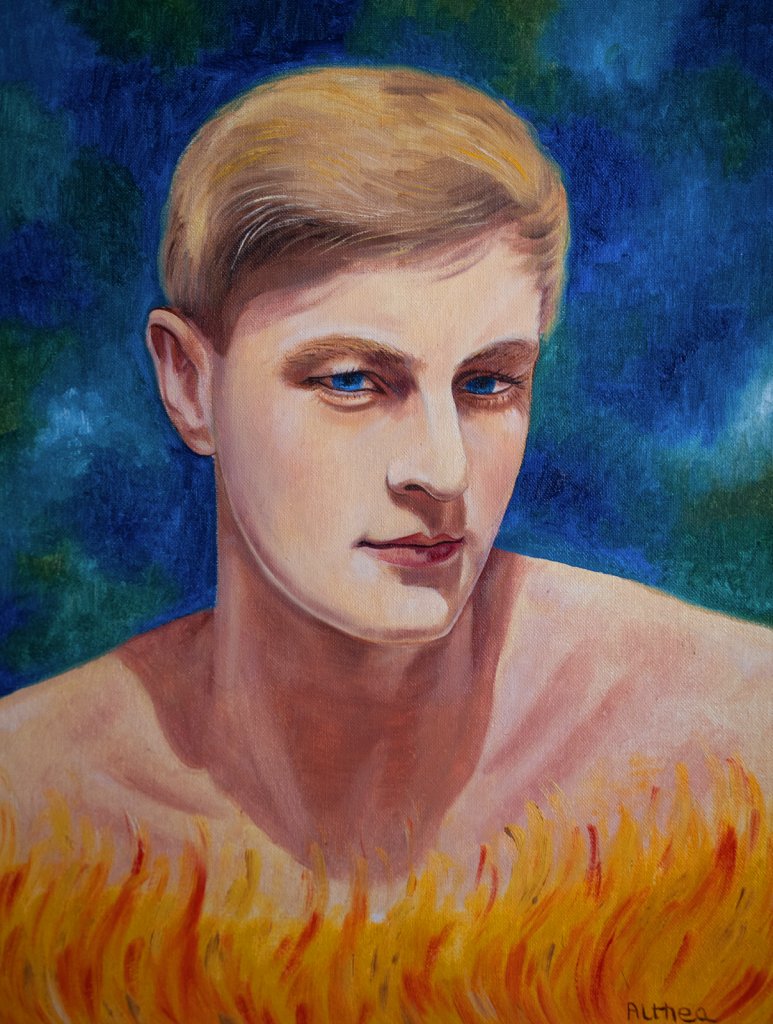

In her cluttered lounge full of antique furniture and beautiful ornaments, 77-year-old Vanessa Wedding scuffles across the room and pulls out two paintings from behind a cabinet – one of a dashing man who resembles a young Robert Redford and the other of a glamorous woman posing like a Hollywood blonde bombshell. It’s hard to tell, but these two precious paintings are of Vanessa, before and after the historical surgery she had in 1969, becoming the first person in New Zealand to change her gender from male to female.

The Auckland trans woman is a pioneer who had gender reassignment surgery – now called gender affirming surgery – when little was known about the procedure, putting her body on the line because she’d desperately wanted to be a woman ever since she was a little boy named Vincent.

Vanessa has rarely spoken publicly about the surgery she had more than five decades ago in Sydney. The memories have been gathering dust like her portraits behind the cabinet. But recently, Vanessa has been reflecting on her life because of ill health. She’s in the final stages of renal failure, suffers from diabetes and has had several strokes. Every day is precious, and she says it’s time to finally share her story and acknowledge her place in the LGBTQ+ history of New Zealand.

“It’s hard to think of myself as a pioneer because I’ve just tried to live my life one day at a time,” Vanessa says, as she holds up and gazes at the glamorous portrait of her as a young woman.

“What I do know is that the day I had surgery 52 years ago was the highlight of my life. It set me free and allowed me to live the life I’ve always wanted – as a woman.”

Born in 1943 in Auckland, Vanessa was the youngest of 10 children and grew up with six brothers. She says she always knew and felt that she was different from the rest of her siblings.

“From a very young age, I wanted to be a girl and not a boy. It was a feeling deep inside of me. I liked pretty things and I liked playing with my sisters’ dolls. I was very gentle and loyal to my parents and always did what was asked of me.”

As young Vincent, Vanessa grew up thinking her desire and longing to be a little girl would be enough for it to happen “magically”.

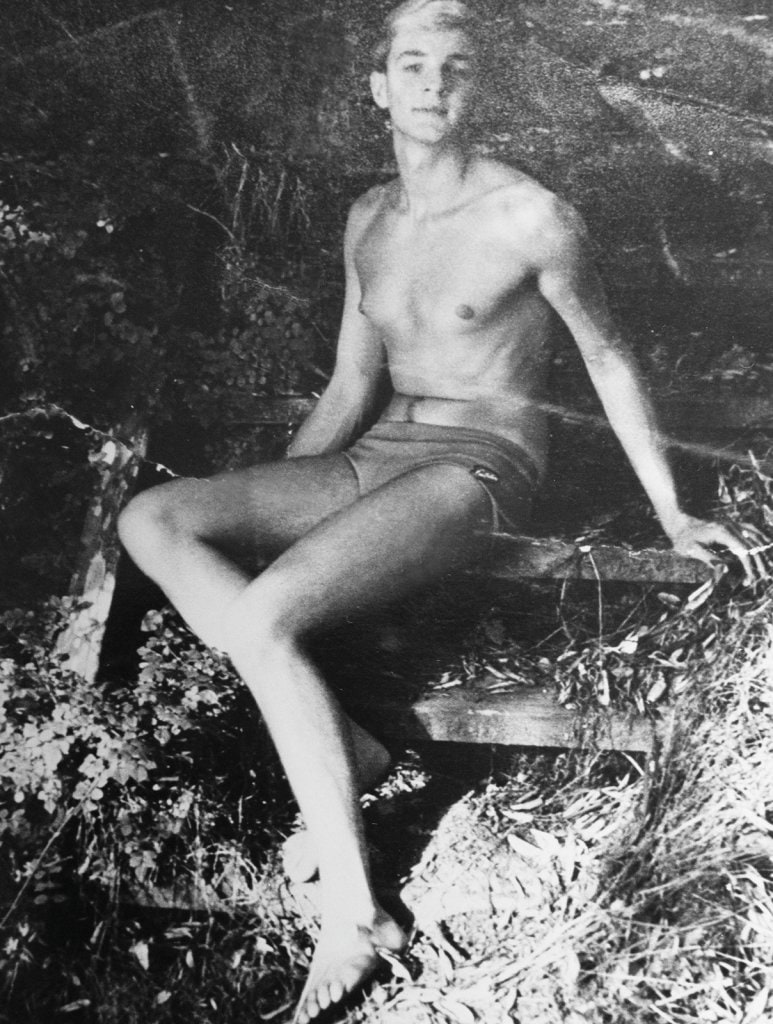

PHOTO SUPPLIED

“I knew how I was built physically, but I thought that magic would happen and that when I grew up, my penis would just fall off and I would become a girl,” she says. “I was very naive.”

When Vanessa was growing up, in the 1940s and ’50s, it was illegal for men to have consensual sex with other men, and gay men all across the country were being prosecuted and imprisoned. During this period, trans men and women were invisible and had few avenues to express themselves.

Vanessa escaped into a fantasy world and wrote stories in her journals about longing to be a girl and the secret romances that she experienced with other boys at school.

“I was very strong in English and I enjoyed writing. My stories were very private and a way for me to express my feelings.”

Vanessa’s father, Charles, died when she was 14, and two years later, her mother, Lilian, discovered her journals. Shocked by the graphic descriptions, Vanessa’s mother sent her to a psychiatrist to try and cure her from what her mother described as a “deviancy”.

“My mother heard many negative things about gay people but never understood,” Vanessa explains. “She was worried it was going to lead me down a path that would get me into trouble.”

Vanessa’s psychiatrist diagnosed her as a homosexual, but she resisted his advice.

“The psychiatrist was toxic towards me,” she recalls. “He prescribed male hormones, hoping that would make me ‘normal’. He was also constantly telling me how I should behave, that I should change my attitude and was encouraging me to find a girlfriend.

“But there was nothing wrong with me and there was nothing he could do or say to make me change how I was feeling. It wasn’t an attitude that I put on or an interest I suddenly picked up. It was innate. I didn’t know what was going to happen to me, but I believed that I could look after myself.”

Vanessa connected with and befriended many gay men her age living in Auckland. One of those friends was a young man from Taumarunui named Trevor Rupe, who became Carmen, one of New Zealand’s most well-known, cherished and controversial trans pioneers. Knowing people like the outspoken Carmen helped Vanessa feel comfortable in her own skin. But she was discovering that she was different from her homosexual peers because she saw herself as a woman, not a gay man.

At 21, Vanessa left home to forge a life away from her family. A talented seamstress, she found work making costumes for local productions and was an assistant at upmarket Auckland department store Milne & Choyce. During the week she would leave home as a man, but on the weekends, she would go to parties and socialise in the city as a woman, in clothing she designed and made herself.

Vanessa’s life changed after she read the story of Christine Jorgensen – a war veteran and the first American trans woman to have gender reassignment surgery, in 1951. For the first time, Vanessa saw that it was physically possible to change genders and she became obsessed with Christine’s journey.

“Reading her story made me realise that things could be done to the body that could put me in a position to physically be a female,” Vanessa says.

At the time, there weren’t any hospitals or surgeons in New Zealand who did this relatively new surgery, but that didn’t stop Vanessa from asking questions and working her way through a long list of local doctors and psychiatrists who might be able to help her.

“I searched desperately for medical professionals who had empathy for people like me and who could understand what I wanted,” she says. “I didn’t like the things I’d been fed by my previous psychiatrists.”

Local medical professionals were very keen to help Vanessa and were interested in doing the first gender reassignment surgery here in New Zealand. Letters to Vanessa show plastic surgeons and gynaecologists were open to exploring how they could work together to make her a woman.

In the end, Vanessa was referred to surgeons at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, who had just performed the very first gender reassignment surgery in Australia. Vanessa was considered a desirable candidate to be the next trans woman to have the operation – the second in Australasia and the first from New Zealand.

“I desperately wanted to be a woman, I felt like a woman and I wanted to get married to a man and be his wife,” says Vanessa. “It wasn’t just about the sexual experience. I wanted to have legal rights and protections as a woman.”

Despite the risks and uncertainties, Vanessa prepared herself and was determined to have the procedure, even raising the $2000 needed for the surgery. She says because the surgery was still new, the Australian surgeons saw her willingness as an opportunity to experiment.

“There were a lot of things that could have gone wrong. The worst-case scenario in my head was that I would become nothing, sexually. That would have been better than how I was feeling, living as a male.”

Vanessa flew to Sydney in February 1969 to undergo psychiatric and physical tests. In June of that year, a month before Neil Armstrong landed on the moon and eight years after she first enquired about the procedure, Vanessa’s surgery was approved, and she went under the knife to change her gender.

“They removed the testicles and inverted the penis into the area around the base of the intestines, where the vagina would be,” she explains.

There were no major complications afterwards, and over the years Vanessa had additional surgery to strengthen the passage.

To feel comfortable in her new body, Vanessa became a nude model in art classes.

“I had to use dilators twice a day for a very long time to keep things in shape so the area didn’t get squashed in and shrink. I tolerated the discomfort because this is what I had always wanted. I was finally a woman.”

Six months after the surgery, Vanessa returned to New Zealand to start her new life. She experienced discrimination, especially in the workplace, and spent many months on the unemployment benefit because she found it hard to hold down a job. In some instances, employers refused to let her use the women’s toilets.

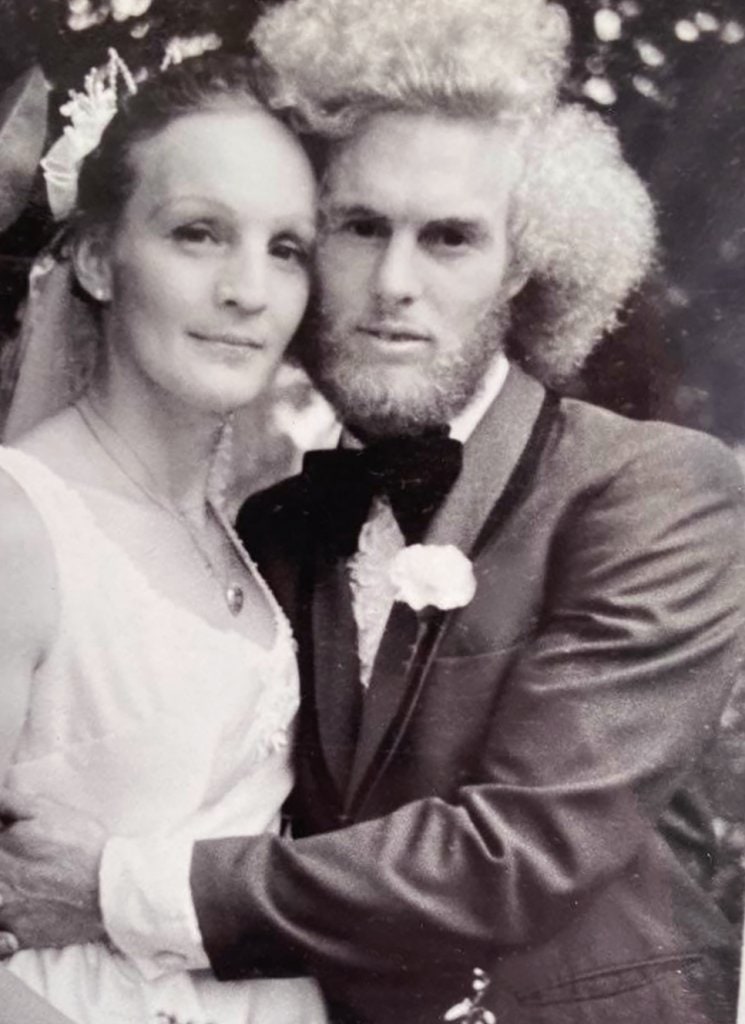

A happier period began when she met and married her soulmate, Mervyn McConnell, after relationships with a string of men who didn’t treat her well.

PHOTO SUPPLIED

Their wedding was controversial and made the front page of the Sunday News in 1977, with the headline “Sex Change Bride!”.

Despite having a church wedding, the ceremony was described as a “marriage blessing” but wasn’t recognised in law after the newlyweds were denied a marriage certificate.

At the time, Vanessa was not legally able to change her gender on her birth certificate, which still identified her as male. Vanessa and Mervyn later applied for a marriage certificate at a different registry office, and it was approved. They had another, smaller ceremony to celebrate the occasion.

“I am a woman. I have done what any other woman is entitled to do,” Vanessa told the Sunday News at the time. “We have beaten bureaucracy because of its injustice.”

Vanessa ended her marriage with Mervyn in 1999, but they are still on good terms.

One of Vanessa’s passion projects after her surgery was the support group she helped establish, called Transcare. It provided emotional guidance to trans men and women who wanted to have gender affirming surgery, especially after it became available in New Zealand in 1980.

“What helped me get through the tough times was the fact that I could help and support others. I was the first in this country to have this surgery – I didn’t have anyone to turn to or ask questions. I spent time with others who wanted to go through the surgery and was a friend while they were in hospital.”

Vanessa may have been a trailblazer in the 1960s, but she says there’s still a struggle for trans men and women to receive consistent health care in New Zealand.

In 2018, the government lifted a cap on gender affirming surgery to address a waiting list extending back more than 30 years. But while some district health boards offer services like voice therapy or breast augmentation surgery, others don’t. Vanessa says issues like these need to be addressed to help with the health and mental wellbeing of trans men and women in Aotearoa, a group that is at a higher risk of suicide.

“These services should be available to people who need it,” she says. “I know from my experience that you can’t function properly until you feel complete. I wouldn’t have lived this long life without the surgery.”