The dark night sky captivates astronomer Nalayini Davies, who tells Jessica-Belle Greer why she wants to protect Aotearoa from light pollution.

Nalayini Davies learnt to look up from her grandfather. “He was a science teacher, and I have clear memories of getting up very early one morning, around 5am, to look at a very bright, naked-eye comet that was in the night sky, and also the total solar eclipse,” she says, as she reminisces about her childhood in Sri Lanka. “At the simplest level, there’s a beauty in the night sky – just simple beauty. But at the next level, it makes you think about the universe, where we fit into the bigger picture.”

Astronomy has remained a strong interest through Nalayini’s life, despite a career in finance. She studied at the prestigious London Business School and launched an international economic development consultancy, Vinstar, in Auckland, with her husband, Gareth. But Nalayini, a long-time member of the Auckland Astronomical Society, would still look to the skies at the end of a day’s work.

Several years ago, Nalayini returned to study part-time for a master’s degree in astronomy, during which she realised just how important the night skies are. “The universe is such a wondrous place and there’s always something to learn and know,” she says. “[Astronomy] is the oldest science, and it’s still a cutting-edge science.”

One of the papers she came across was “The New World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness”. The statistics showed that more than a third of humanity could not see the Milky Way – and more than 99 percent of people in America and Europe lived under light-polluted skies.

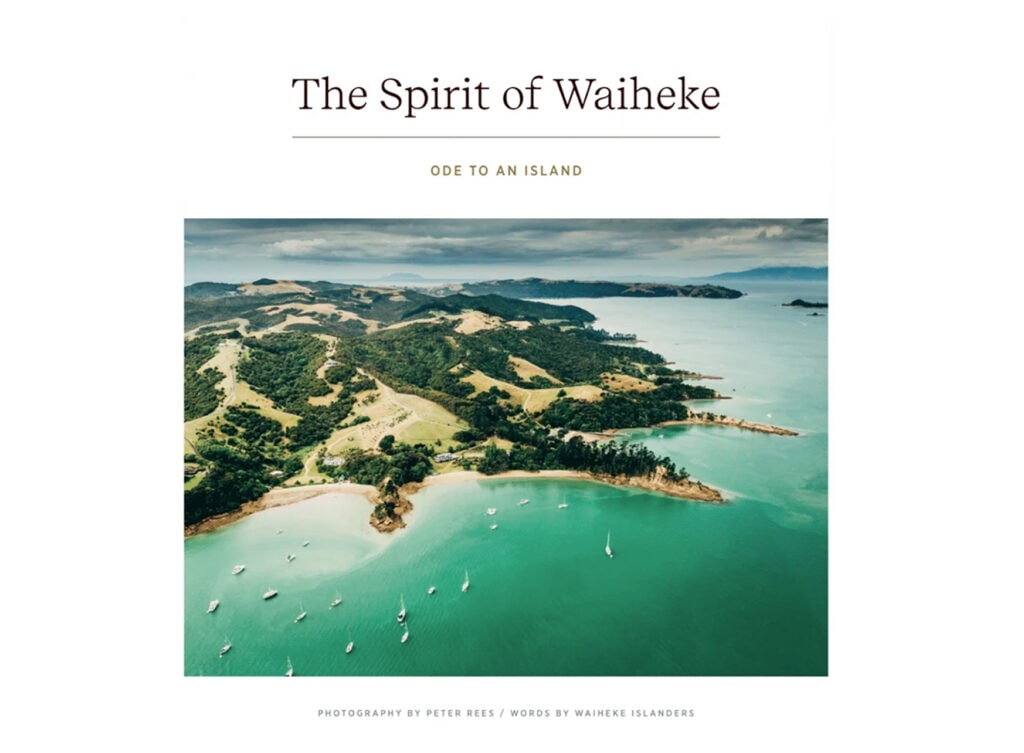

From her holiday home on Waiheke Island, where she has come and gone for 32 years, Nalayini can see the Milky Way in all its sparkling nebulosity. She decided to measure the darkness of Waiheke’s night sky and realised it was dark enough to be accredited by the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), a non-profit that works to protect the skies for star watchers to come.

Protecting our sky

Light pollution is another form of pollution that puts our earth in a precarious position. The sun, the moon and the stars have influenced breeding, migration and hunting behaviours from the beginning of time. But with the recent introduction of artificial lights that operate on a blue wavelength like the sun – including LEDs, laptops and smartphones – we are falling out of the natural order of things.

For us humans, the American Medical Association reports that brighter residential night-time lighting suppresses melatonin and has been associated with reduced sleep times, impaired daytime functioning and obesity. Other research has shown that altered circadian rhythms due to factors including bright lights at night have led to an increased likelihood of cancer, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, and immune dysregulation.

“As life forms on earth, we have evolved with the sunrise and sunset,” says Nalayini. “The circadian rhythm is built into the way we live, from human beings right down to insects.”

Artificial light also affects nocturnal animals, which rely on the cover of darkness. Blue lights – including energy-efficient street lamps – disorient the navigational sense of birds, turtles, fish and many insect species, often leaving them helpless under the halo. “There’s a very serious view, based on scientific findings, that it’s impacting biodiversity,” she says. “I think it’s a necessity in today’s world, so I’m not saying, ‘Switch off all your lights,’ but we have to use it smartly.”

Nalayini has flicked off the switch that lit up the bush at her Waiheke home before she knew better. She suggests installing timers, using lights only when you need them and buying bulbs in a warmer, orange glow.

The astronomer founded Dark Sky Waiheke Island to engage with those who have influence over Waiheke’s light pollution, as the IDA tightened its requirements for dark-sky status. It’s been three years of work so far, and she hopes to be successful in a matter of months.

For Nalayini, the effort is worth it, particularly because Waiheke is known for its native birdlife. In terms of outreach, the island is only a short ferry ride from central Auckland, where 35 percent of New Zealand’s population lives. “We can really share this with so many people … we’re all on our little journeys of discovery.”

A central element of the campaign is sharing the importance of protecting the night sky with the Waiheke community, and it’s gaining genuine interest. Dark Sky Waiheke Island works with local families, schools and Scouts. “It’s all about knowing,” she says. “The more you know, the better you can protect.”

Art lovers are reached through exhibitions Nalayini works on, and moviegoers’ imaginations are captured when they leave the cinema and pass the telescopes that are sometimes set up outside. Nalayini writes a column for the Waiheke Weekender and has contributed to a new community book, The Spirit of Waiheke.

Through her work with Dark Sky New Zealand, Nalayini has helped Aotea/Great Barrier Island and Rakiura/Stewart Island become recognised as dark-sky sanctuaries. Her husband has caught her enthusiasm and they volunteer together. “It’s been an unexpected but really rewarding experience,” she says. “We do this as a contribution to the community.”

Along the way, they have trained locals to become dark-sky ambassadors – Great Barrier Island now has a handful of eco-astro tourism businesses.

Nalayini is chairperson of the Astronz charity and vice president of the Royal Astronomical Society of New Zealand. She dreamt up the idea of New Zealand becoming the first “dark-sky nation” at one of the many conferences she attends. “Every part of New Zealand is accessible. Anybody who’s prepared to drive 30 minutes can see really dark skies,” she explains. “In many ways, we’re leaders in dark skies.”

The Milky Way can be seen from 96.5 per cent of our land area – the same Milky Way that ancient navigators and agriculturists followed, though the Earth has changed significantly underneath it since.

In protecting our night skies, we can continue to look up and appreciate our place in the universe. For Nalayini, the dark sky connects her to the astronomical events she shared with her grandfather – and those she hopes to share with generations to come.

“The night sky has remained the one constant throughout history, across the whole world and across generations,” she says. “If you look at it that way, it’s pretty special.”

Photography by: Alamy & Getty