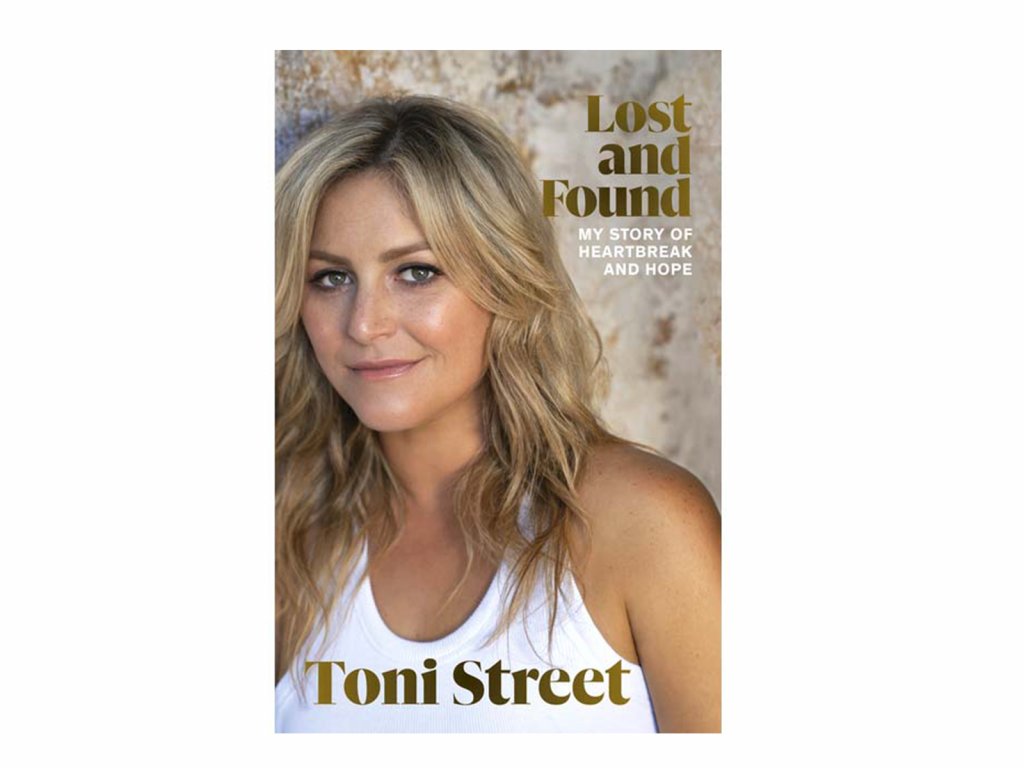

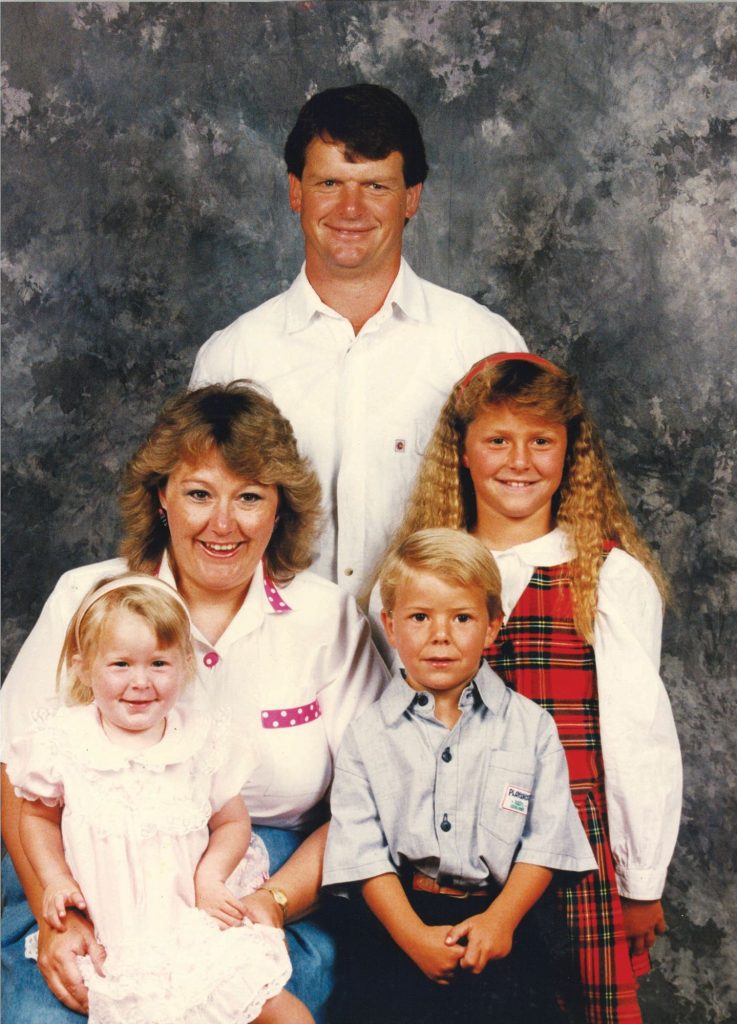

Broadcaster Toni Street shares the day her beloved 14-year-old brother Stephen died. It was the third tragic loss for her parents, who had already suffered the deaths of daughter Tracy and Toni’s twin brother Lance.

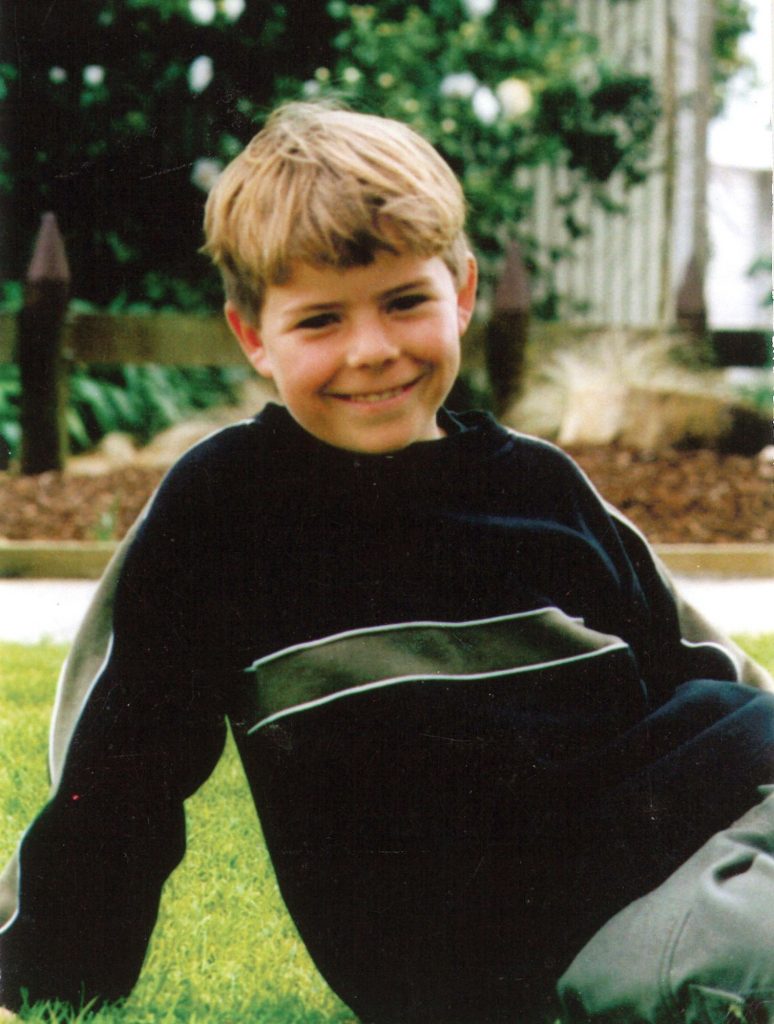

Like many teenage boys, Stephen loved sport and he loved hanging out with his mates. But he was happiest out on the farm with Dad. They were a tight duo. Every day after school he would walk in the door, throw down his schoolbag and head out to see what Dad was up to.

Stephen wasn’t particularly academic; he struggled at school, and I know he found that doubly tough because schoolwork came quite easily to Kirsty and me. But he had other skills. He was a courageous little rugby player. He wasn’t big, but he was wily and could outwit his opponents. He was amazing with his hands – skills honed by all those hours spent mucking around in the shed with Dad. He was a perfectionist, and he was driven. When he wanted something, he would put his mind to it and spend as much time as he needed to make it happen.

I remember when he was desperate to get a cellphone, so he collected bottle caps to trade for money. It took a lot of bottle caps, but Stephen was determined. And when he wanted a PlayStation he struck a deal with Mum and Dad that if he learnt his times tables they would buy him one. He just went for it; for months he practised and practised and eventually nailed it. He got his PlayStation.

We all remember the day he came home with his school report at the end of third form. He walked in the door and flopped on the couch face-down. Mum realised he was crying, but all he would say was “I’ve done no good.” He had failed maths, which was meant to be his strongest subject. Mum picked him up and cuddled him like a baby, doing her best to console him. She reminded him about all the things he was great at that other kids might not be. We didn’t know what else to do. It was heartbreaking.

Then Mum told him about John Britten, the Christchurch motorcycle engineer who was dyslexic but had still managed to create the world’s fastest motorbike. She told Stephen that perhaps he was dyslexic, too, and promised him “we’re gonna get it sorted”. She said she would buy him a copy of Britten’s biography and read it to him. “You will be so clever, Stephen, you could 100% build a motorbike like that,” she told him. He looked up, his beautiful brown eyes sparkling, and said, “Do you really think I could?” The idea that someone who struggled like him at school could still be successful filled him with hope.

‘Yes! I know you could,’ Mum said, and she meant it. That summer had started so well. I finished my final year of school on an absolute high. I had loved being head girl, I got an A bursary and was excited about moving away from home. I had been awarded a sports scholarship to study at Lincoln University in Canterbury, and would train at New Zealand Cricket’s High Performance Centre, attached to the campus.

I spent that final summer at home playing cricket for Central Districts, relaxing at the farm, doing plenty of socialising with family and friends, and hanging out at the surf club. I look back on those few weeks of holidays as a sort of utopia. Little did I know my world was about to implode.

Everything changed on the morning of January 7, 2002.

I had been in Dunedin playing cricket and we had taken a very early flight back to Christchurch. Milling around at the airport as we waited for our bus to Lincoln, I had no idea that back home my family was breaking into a million pieces.

The night before had been much like any other back in Taranaki. Mum and Dad had friends over for dinner, and Stephen and Kirsty decided to have a sleepover in my bedroom. I had a queen bed, of which they were hugely jealous because they still had their little single beds, so occasionally they begged Mum to let them bunk in mine for the night when I was away playing cricket.

When Mum went to tuck them in at about 11pm they had built a pillow barrier down the middle of the bed and were arguing over who had the most room. Mum settled them down and pulled up the duvet, and then out of nowhere Stephen suddenly asked her about the John Britten book.

“Have you bought it yet, Mum?”

It had slipped her mind, but it hadn’t slipped Stephen’s. Mum felt terrible. “Sorry, darling, we’ll go and buy it tomorrow, I promise.”

“OK, Mum, night night. Love you.”

That was the last time she would see him alive. The next morning Dad crept in at about six and got Stephen up to help him with the milking. The night before, Stephen had had a sore foot that was a bit swollen, so Mum had said, “He’s not going up to the shed like that.”

But Dad, being Dad, thought, “He’ll be right.” Besides, he and Stephen wanted to play golf that morning so they were keen to get the jobs done early.

Dad was milking and asked Stephen to jump on the quadbike and go and put out a bit of fencing in a paddock about 200m away. It was a totally normal sort of thing — Stephen knew the terrain and had been helping with jobs like this since he was little.

It should have been a quick job, and when Stephen hadn’t returned after a while Dad started to wonder why not. He set off across the paddock on foot to find him. Maybe the bike had broken down, or he had run into trouble with the fence job.

As he came up over the top of a hill he saw him.

The quadbike was flipped on its back and Stephen was pinned underneath it. Dad broke into a sprint and managed to lift the quadbike off the lifeless body of his son. He knew immediately that Stephen had died, but he began CPR, desperately trying to pump life back into him. He could not accept this — no way was he taking another dead child home to Wendy. “Come on, son, come on!”

The CPR wasn’t working, so Dad scooped Stephen up into his arms and carried him back to the milking shed. All he could think was that he had to save him, he had to bring him back to life. He laid Stephen on the floor of the shed and grabbed a length of live electric fencing. It was desperate and crazy, but in that moment it was all he could think of. He thought maybe he could zap his boy back to life, as though the live wire was some kind of makeshift defibrillator. He was panicking and crying and begging Stephen to come back but it was hopeless. The electric current did nothing and our boy was gone.

I can’t imagine what was going through Dad’s mind as he carried Stephen back across the farm to Mum. It haunts me when I think about it even now. How could they survive the death of a third child? Dad laid my little brother gently down on the back lawn and ran into the house yelling for Mum, who was still in bed asleep. “You’ve got to come, you’ve got to come quick!”

What awaited her – and my 11-year-old sister who was also woken by the screaming – was worse than anything she had dared fear. The son she loved so deeply and fiercely was lying dead on the patch of grass where Lance’s funeral had taken place 16 years before.

Mum took in the scene, her boy lying dead on the wet grass, and she could not accept what she saw. She ran inside and called an ambulance, crying and shouting, “Send help, please send help!”

The operator had difficulty understanding what she was saying. Then Mum said, “Don’t worry, it’s hopeless, he’s dead,” and threw the phone down before running back outside. She was angry now because Stephen was covered in mud and cow shit, which he would have hated. For a country boy, he had a surprisingly low tolerance for dirt.

She ran in her nightie the 300m to my grandparents’ house, across a paddock in bare feet and over a little footbridge. “Stephen’s dead!” she screamed, before turning on her heels and running back. She didn’t know what to do; her son had died and it was the end of the world.

In their stunned state my parents eventually carried Stephen inside, changed him out of his dirty clothes and laid him on his bed. It was important to Mum to make him comfortable and safe and warm. The ambulance arrived, but obviously there was nothing they could do. The police turned up and asked some questions, because that’s what happens after a sudden death. Then everyone was gone and it was just Mum and Dad, my sister and their dead son, who right now should have been loading his golf clubs into the car and heading off with Dad.

They knew they had to tell me what had happened. Mum managed to track down the cellphone number of my team manager, Jackie, and somehow found the courage to dial it. She calmly explained what had happened and asked to speak to me in a quiet area. Jackie took me to a side room at Christchurch airport and handed me the phone. “Toni, it’s Mum. Stephen’s had an accident.”

At first I thought he must’ve broken his leg, or maybe even his neck. He had been given a motorbike for Christmas and in my mind I was already cursing the thing.

“Is he OK? How bad is it?” “It’s bad, Tones. He’s died.” The next few hours are a blur.

I remember walking out of that room and staring blankly at my teammates, who realised something bad must have happened. A couple of the girls knew Stephen and they tried their best to comfort me, but I felt an overwhelming sense of claustrophobia. I needed to get out of there.

The weird thing is that from the outside I probably seemed calm. A deep state of shock was setting in and it felt as if I was dissociated from my body. I don’t think I cried. The reality was too horrible to accept. It simply could not be true that my little brother would not be there when I got home. He was such a vital and special part of our family; it wouldn’t work without him.

I’ll never forget that walk off the plane and across the tarmac in New Plymouth that day. It was like I could feel the years of grief and anguish that lay ahead, weighing me down with every step I took towards my devastated family.

We drove home in a stunned silence. I knew those roads like the back of my hand, but the view wasn’t the same anymore: everything seemed different.

I walked down the hallway straight to Stephen’s bedroom. There was no escaping it now. There he was: my brother tucked into his bed looking almost exactly the same as before but also completely, horrifyingly different.

Some people draw comfort from seeing their loved ones after they’ve passed away, but not me – I didn’t like it at all. That was not my brother in that bed. The Stephen I knew and loved was gone and in his place was a lifeless body. Every part of me ached for my little brother.

Word spread quickly and the house began to fill with people. In our little pocket of the world families put down roots and don’t move, so these were people who had known my parents forever. The ties ran deep. They had been there when Lance died and when Tracy died, and they were here now, with a shared sense of utter disbelief that it could have happened again. Every single person who walked into our house was in a state of shock. But they swooped in, wrapped us up in love and support, and between them made sure we were not alone in those first few days.

Eight cups of tea a day is normal in a farming house, but this was more like 20. I can still hear the kettle boiling, the clinking of the cups, teaspoons stirring and the dishwasher being loaded and unloaded. We had to talk to everyone who came through the door and it was exhausting, but I was so grateful for the busyness of the house. We talked, we passed around the biscuits, we made another pot of tea. It helped to distract us from the hideous truth that our 14-year-old Stephen, the darling of our family, lay dead in the bedroom down the hall.

I was so relieved that it wasn’t left to Kirsty and me to hold our parents together. We were young and struggling with our own emotions, let alone coping with Mum’s and Dad’s. I genuinely remember thinking “I’m so glad you came” about every person who turned up at our front door during that period, because they were helping me to help my parents. I didn’t want us to be alone.

Most visitors would go to see Stephen in his bedroom. I continued to struggle with it. I didn’t want to see him like that. It broke my heart, and I remember feeling really scared of the whole situation. I suppose, looking back, I was in denial. If I acknowledged him in that bedroom properly I was accepting that he was dead.

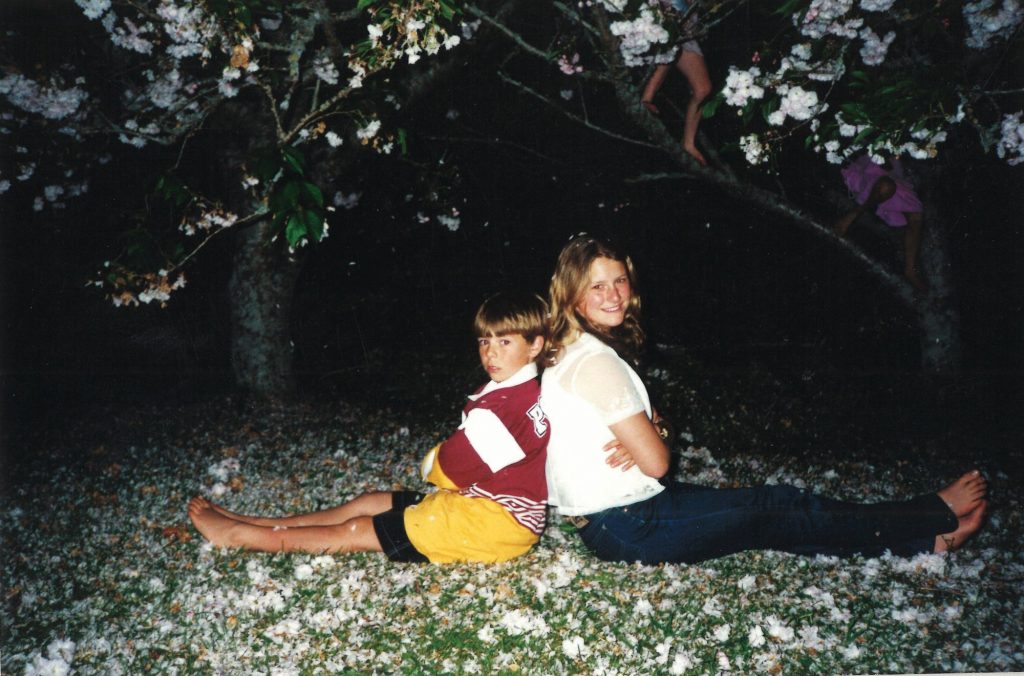

Of course I did spend time with him, because a part of me must have known it was important, and now I am pleased I did. It helped me to process that yes, this was real, and no, we weren’t getting him back. But now when I close my eyes and remember him it’s the real Stephen I see. The one who’s kicking a rugby ball around on the back lawn or smiling up at me with his cheeky grin. It’s the brother who hugged me twice at the airport as I left for my cricket trip, the last time I would ever see him.

When I close my eyes and remember him it’s the real Stephen I see… smiling up at me with his cheeky grin.

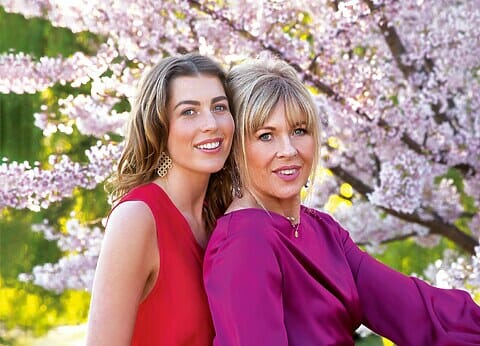

My grief seemed bottomless. There were times I cried so hard I couldn’t breathe. Mum was so strong, with a steely determination that her boy had to be remembered and celebrated properly. She put together a big photo board filled with pictures of Stephen taken throughout his life. The day before his funeral I stood in front of that board, taking in every single image of the precious boy I felt so lucky to have called my brother. Suddenly the horror of how much we had lost overwhelmed me. Mum found me sobbing and gasping for breath on the floor.

I now realise it was a panic attack. My feelings in that moment were so intense I thought I was going to die of sadness. How Mum managed to hold it together seeing me in that state I don’t know, because she must have wanted to join me in a heap on the floor. But she gave me a paper bag to breathe into and comforted me as I sobbed.

As a family we lived in a kind of no-man’s-land in those first days after Stephen’s death. We were just drowning in sadness. Mum was adamant the funeral should happen soon, knowing from past experience that delaying it only prolonged the pain. Almost a thousand people came to Stephen’s send-off, packing out the New Plymouth Boys’ High School hall. They came and they wept with us, and every single person there showed us just how loved Stephen was and how much they cared about our family. Mum had firm ideas about how the day should be: it was a celebration of her boy, and she didn’t want any of us wearing black. “That’s what you wear when old people die,” she said.

My memories of the day are strangely patchy; I think it’s because I was traumatised.

I remember thinking beforehand that no way would I be able to get through the funeral, but I managed to pull myself together. I wish now I had been strong enough to make a speech, because there was so much I would love to have told everyone about Stephen and what he meant to me. But I just couldn’t. Instead, I read a poem.

Mum, on the other hand, was extraordinary.

She did us proud, standing up in front of all those people and talking so beautifully about her son. She wanted every person in that hall to know how awesome Stephen was, how cheeky and funny he was, how he loved the farm and his rugby, and how he was growing into a thoughtful, kind and hardworking young man who made us all so proud.

I honestly don’t know how she did it, but I’ll always remember her standing up there beside her son’s coffin, promising him he would never be forgotten.

At the end, as Stephen’s coffin was carried out of the hall, the Boys’ High students, all 1200 of them, performed the most spine-tingling haka I’ve ever witnessed. It was unforgettable.

After the funeral I was hit with a crashing sense of “what now?”. I had to reimagine my life without my brother in it and I didn’t know where to start. I didn’t have any desire to do anything. For the first time my future felt scary and I wondered if any of us would ever feel happiness again. It didn’t seem remotely possible.

I had no idea how I could survive the pain, or this new life without my little brother.