Artist Yuki Kihara tells Dionne Christian why crossing the line is in her nature.

The year was 1995 and Yuki Kihara was on a roll. Then 19, she may have had to repeat her first year of fashion design at Wellington Polytechnic – “because in that first year all I did was party and get drunk” – but Yuki took out the Dupont Lycra competition, “Action Pasifika – nothing moves like Lycra”, and her award-winning long, tight-fitting graffiti dress, Bombacific, was obtained by Te Papa for its collection.

After being bullied at college, then battling with her conservative parents to be allowed to leave school for “less academic” tertiary study, the win and Te Papa’s purchase were all Yuki needed to confirm that she was where she was meant to be.

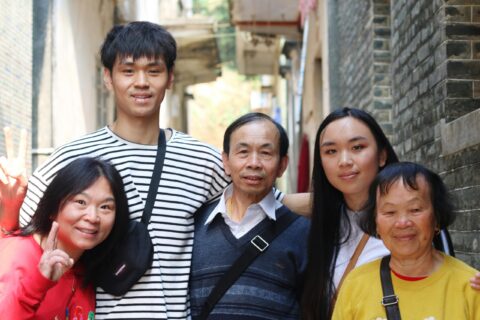

“That sealed it for me to say, ‘You know what, Yuki? You got it and don’t let anyone else tell you otherwise!’ I knew I was on the right track,” she says, adding that it also reassured her Sāmoan mother and Japanese father she was heading in the right direction.

Some 24 years later, in 2019, Creative New Zealand announced that Yuki would be Aotearoa’s representative at the world’s most prestigious art fair, La Biennale di Venezia (the Venice Biennale) – the 126-year-old international exhibition where thousands of artists and art lovers gather to celebrate the best in contemporary art. It was meant to go ahead this year, but due to Covid-19, Yuki will instead take part in the postponed event in 2022.

Chosen from 17 potential representatives, Yuki’s selection marked some significant milestones. She is the first person of Pacific descent to be presented by New Zealand, the first fa‘afafine and the first who hasn’t had formal arts training. Of her selection, Yuki declared that the glass ceiling had been well and truly shattered.

But she started fracturing it years ago. Ever since Bombacific, Yuki has built a reputation for unapologetic art – mainly photography and film – that challenges accepted post-colonial histories and how Western ideals have been foisted on Pacific peoples.

Yuki does so from the point of view of a fa‘afafine, which, translated from Sāmoan, means “in the manner of a woman” and is widely regarded as a distinct third gender identity in Sāmoan society.

Provocative, confronting and always engaging, her work has attracted attention far beyond the Pacific. In 2008, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York held a solo exhibition of her work, Shigeyuki Kihara: Living Photographs – the first time a New Zealander had been the subject of a one-person show there. The museum later added some of her pieces to its permanent collection.

Similarly, art museums in Los Angeles, the UK, Australia, Canada and across Europe hold her work. She’s presented at international art fairs and was recognised in Aotearoa with an Arts Foundation New Generation Award in 2012, the same year she won the Paramount prize at the annual Wallace Art Awards. Last year, she became an Arts Foundation Laureate. She’s also a research fellow at the National Museum of World Cultures in the Netherlands, and has travelled extensively around Europe making and talking about her work.

Right now, Yuki should have been in Venice enjoying the biennale and the extraordinary amount of exposure it brings. But, ever the clear-eyed pragmatist, she’s accepted the delay because it means more time to finesse her work.

Creative New Zealand will announce next month what her presentation at the 2022 Venice Biennale will involve, but given her past form, it is likely to reflect on the shared histories between Aotearoa and the Pacific, highlighting new insights into that relationship.

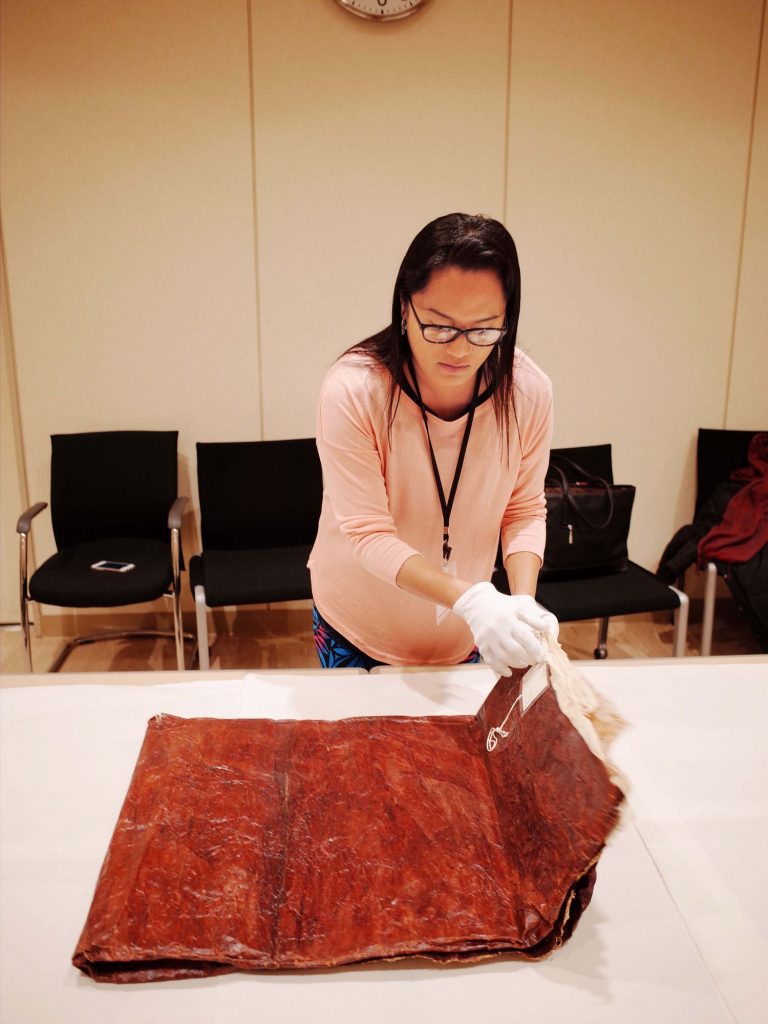

From childhood, Yuki saw things differently. Take, for example, a visit to Japan’s National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku) in Osaka when she was just seven years old. She recalls accompanying her father there and being fascinated, not just by the taonga on display, but how the dark lighting gave the cultural treasures a “spooky” look.

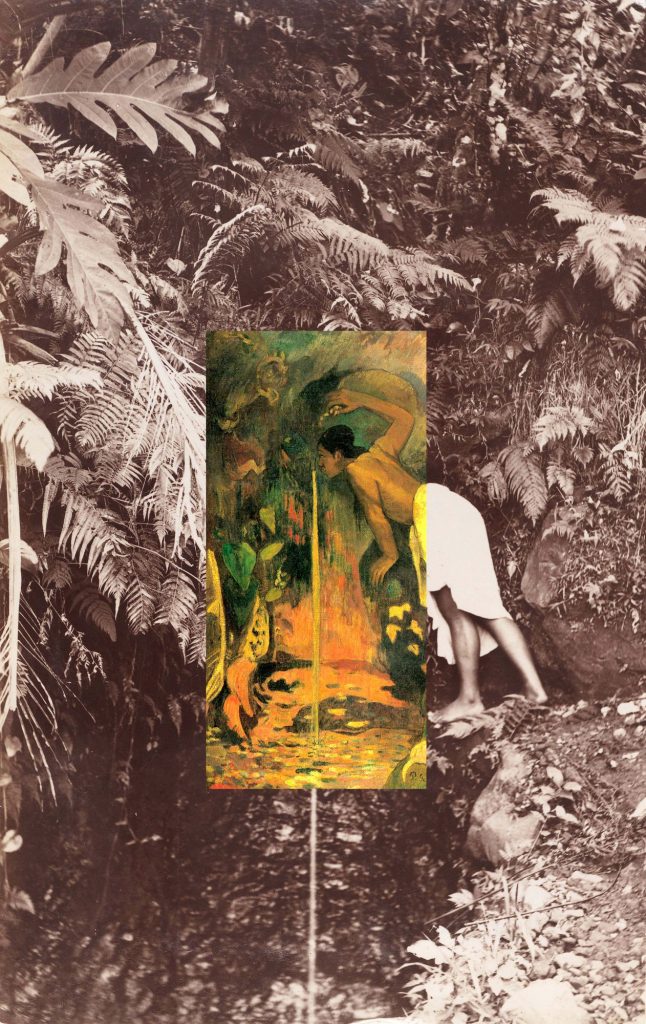

Later, as a fashion design student doing research at Te Papa, she happened across a collection of black and white photos taken by New Zealand photographers in early 20th-century Sāmoa. They purportedly documented authentic landscapes, lifestyles and people, but many of the subjects were photographed nude and presented as exotic sexual objects. Why, she wondered?

“Then I realised that museums had a lot of decolonising to do in terms of the displays, the taonga, the way it was presented and decontextualised and catalogued, conveyed, translated,” Yuki says.

PHOTO BY YUKI KIHARA

“Making art has been a way [for me] to negotiate places. I use my artwork to negotiate being at the intersection of geographic borders, cultural borders, gender borders, racial borders. So my work has always been a critique of borders, how they are made and how they are used to control.”

She says growing up at the junction of so many borders has allowed her a unique perspective of both being inside and outside various cultural contexts and situations. When it comes to making art, that can be seen as a blessing. But it was less so when a 16-year-old Yuki arrived at a conservative boarding school in Wellington.

“I had a very unique outlook and experience in life that nobody else did,” says Yuki. “I was more mature than the rest of the people in my school, who came largely from farming families and who had never travelled… I spoke three languages [Sāmoan, Japanese and English], I had lived in Sāmoa, Japan and Indonesia, and I also identified as a fa‘afafine.

“Most of the other pupils lived a very privileged but naive life, and I couldn’t live that way because of the experiences that I had. I was bullied; I always had to be a step ahead of them to figure out what their next move against me would be.

“I’ve heard many successful people say, ‘I wouldn’t change anything for the world’, but personally, I’d like to – I would love to. But again, that would mean all these things that accumulated in my history and led me to where I am now wouldn’t have happened… They are sometimes difficult to deal with because they have become the saboteur in my head that always lingers around, feeding into my insecurities, but I have been able to find ways to tame them. Art helps.”

Not surprisingly, Yuki couldn’t wait to leave school. Told by her parents that she couldn’t study art, she instead enrolled at fashion design school at Wellington Polytechnic (now Massey University).

She also eventually shifted away from the relatives she was living with to a flat with other fa‘afafine, where she had “the time of my life”.

While Yuki was happier, fashion school didn’t fulfil her artistically, with its focus on industry training and lessons on things such as business management, fair labelling laws and creating made-to-measure collections – although she now acknowledges those elements have proved immensely useful. While her classmates were training to be fashion-industry ready, Yuki was using cloth as a sculptural material to make theatrical and avant-garde creations.

“They had no functionality; it was all about the presentation,” she says.

In 2000, she produced a series of T-shirts which subverted the logos of big businesses. Parodying the brand names to make a political point (many of these companies relied on Pasifika workers, often earning low wages) showed youthful rebellion, but also Yuki’s discomfort with an increasingly sanitised, homogenised and corporatised life.

The T-shirts were displayed in a small Auckland art gallery and hung by clothes pegs from a piece of string in a Wellington hair salon where Yuki worked part-time. It was here that they caught the eye of Te Papa curator Ian Wedde, who displayed them in a 2001 show called More or Less alongside a Gianni Versace retrospective exhibition.

A media storm followed, with articles about copyright infringement appearing in major newspapers. New Zealand Listener dubbed it “the Shigeyuki Kihara scandal”, while a fresh- faced 26-year-old Yuki was interviewed and photographed for several other publications.

Although no legal action was taken, the furore marked a turning point in Yuki’s approach to her work – and a shift from fashion to photography and film.

“I found more freedom to generate the kinds of conversations that I wanted to have in the gallery space more than in boutiques. I wanted to treat a gallery space not necessarily as a space to exhibit things, but as a space to present an idea and generate discussions around it,” she says.

Yuki divides her time between Aotearoa and Sāmoa, deciding 12 years ago to be predominantly based in Sāmoa (although travel restrictions mean she’s spent most of 2021 in New Zealand). While it’s the arrangement she prefers, she acknowledges it hasn’t always been easy.

“For the first two years, I was complaining like a b****, like a spoiled brat – ‘Sāmoa doesn’t have this, Sāmoa doesn’t have that, slow internet connection, la la la’. But after all the whining and looking at the work of other artists, I began to realise that other artists don’t whine. They are actually making the best of what is available in Sāmoa, and that’s when I realised there were other ways,” she says.

“I enjoy the challenge because I always find, you know, one has to discipline one’s self to work within limits. Having limited resources doesn’t really devalue your creativity, it amplifies it. When you have everything, that’s when you get confused. When you have limited resources, that’s when your imagination thrives.”