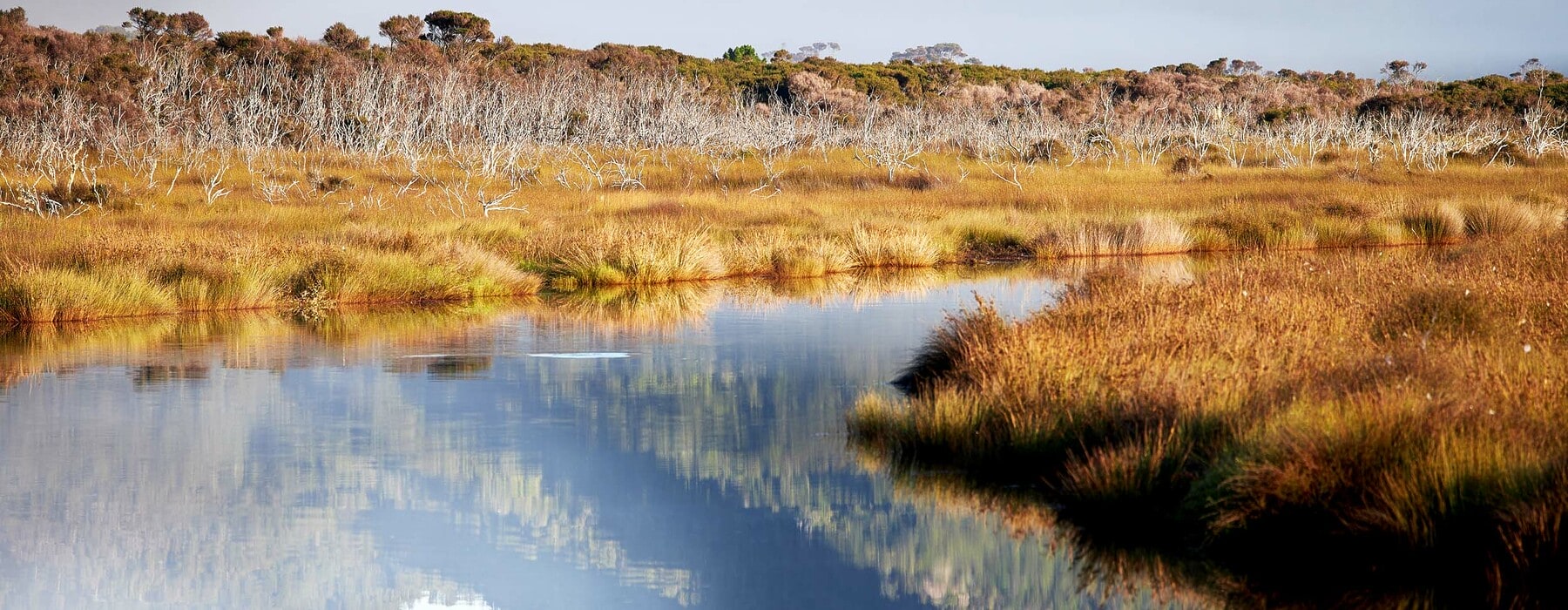

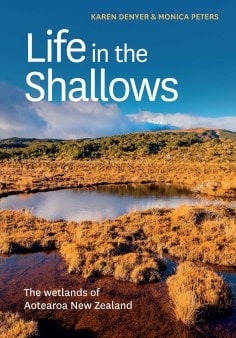

We have destroyed 90 percent of our wetlands and the race is on to preserve what’s left while we still can, say the authors of a new book. Karen Denyer and Monica Peters share their love of this precious part of our environment.

Karen Denyer

Why are wetlands so important?

MONICA PETERS: From a Western land management perspective, we’ve only cottoned on to the fact that wetlands are important because we have so few left. Over the last 150 years or so, they’ve been infifilled for everything from housing, roads and factories to farms, or excavated into oblivion for marinas and other coastal developments. I live in the Waikato and there’s a very, very expensive array of canals, stopbanks and floodgates to do the job that a vast wetland stretching across the Hauraki Plains once did – soak up excess water and release it slowly like a giant sponge, while cleansing and purifying it along the way. There are also all the quirky creatures that breed and live in wetlands, and the special plants that can tolerate having wet feet either full-time or part-time. But that’s just from an ecological function and biodiversity perspective; tangata whenua, duck hunters, wildlife photographers, fifishermen, landscape architects and lovers of nature – each could provide their own unique narrative describing why wetlands are so, so important.

Why are they so important for carbon sequestration?

KAREN DENYER: As we say in the book, the things wetlands do for us free of charge is staggering – stripping nutrients and silt, storing floodwaters and recharging aquifers, to name a few. The dollar value of the “ecosystem services” that wetlands provide is 10 times more than either farmland or forest.

They are also, finally, now being recognised for their role as carbon stores and sinks. Globally, peatlands store around twice as much carbon as all the forests of the world. In the Hauraki Plains, the healthy Kopuatai peat wetland is still actively storing carbon, but the drained and farmed peatlands around are sinking at an alarming rate of one metre per 50 years, and emitting up to 32 tonnes of carbon per hectare per year as they do so.

Unfortunately, wetlands still fall into the too-hard basket when it comes to bringing them into our carbon-trading markets. It is expected that, globally, many peatlands will release carbon if the climate warms and dries. If we let that happen it’s going to be a huge problem for us and our planet. Trees are great at temporarily storing carbon, but wetlands can lock it up indefinitely – that’s where the coal and oil that we are burning today came from. There are potential solutions out there, we just need to think outside the box. In fact, Waikato Regional Council is embarking on a big research project into peat and carbon at present, showing real leadership.

What are the biggest threats to wetlands locally?

KD: People, sadly. Wetlands are still being cleared or drained, even with strong new rules to protect them. In fact, we have had strong rules for years, they just haven’t been well enforced in some parts of Aotearoa. During these past dry years some wetlands have become terribly polluted. But people are also their biggest saviour, as more and more people realise their importance and are keen to help restore them.

MP: Our desire to radically reshape the landscape to fulfil economic imperatives has left us with a tenth of the wetland areas that once blanketed so many parts of Aotearoa. We’ve introduced sharp-toothed mammals that predate birds and insects; weeds have been allowed to take hold above ground and underwater, and introduced fish freely compete with our native fish. Karen has mentioned pollution, and there’s climate change pressures as well. When you were researching the book, what did you think were the most exciting or promising work scientists are doing?

KD: I would have to say Dr Bruno David’s use of bio-acoustics, using sounds to understand what’s going on in the environment, and even to control machines in response to the sounds that animals make. There’s a pretty gruesome, but ultimately uplifting example involving our apex predators, eels, that deals with what happens when they get caught in a pump during a flood. There’s also some cool stuff being done with environmental DNA that can give us early warning signs that estuaries are under stress or tell us about what our lakes were like in the past so we can plan for their future.

What came through really strongly though is how New Zealand is increasingly blending Western science and the significant body of Māori knowledge built up over hundreds of years of interacting with wetlands and their species.

What does mātauranga Māori bring to our understanding of wetlands?

KD: Western scientists have had barely 200 years to learn about New Zealand wetlands, and most of them have been limited to researching a fraction of the wetlands that once existed, many now degraded and with half their species gone. It is like doing a jigsaw without the picture on the box and only 10 percent of the pieces. Māori lived in and beside wetlands for more than 800 years and had the full picture. They have so much intimate knowledge and experience of wetlands; how they work, how they changed seasonally, and how they once were. They observed and interacted with species that are now extinct. It has become clear to most scientists – Māori and non-Māori – that to fully understand a natural area it makes sense to first talk to local iwi and find out what they know from oral history and their own observations. Blending traditional knowledge with Western science dramatically increases our understanding. For instance, learning where and when fish species that are now rare were once harvested can help us locate and protect spawning sites or migration pathways.

MP: Mātauranga Māori brings a dimension that has been missing for a long time, with predominantly Pākeha scientists and land managers leading wetland initiatives. Restoring our degraded landscapes isn’t

just about an ecological fix, it’s situating restoration actions into a wider social and cultural setting. That means looking at a much bigger and nuanced picture – not just at the natural environment and the disastrous impact of human activities, but also how people have valued, used and understood wetlands over time.

l VISIT Add a wetland to your itinerary when you’re travelling around New Zealand, so you can fully appreciate the great diversity of scenery, wetland types, plants and animals our wetlands have to offer. Find a wetland near you by visiting the National Wetland Trust at wetlandtrust.org.nz – the trust has a directory of wetlands to visit, ranging from wetlands right in the thick of our cities to more remote sites.

How can ordinary people help save or restore wetlands?

KD: Firstly, by getting to know them. We find out where you can visit a wetland (some are listed in the book), ideally one with easy boardwalks and interpretation signs, and just go and enjoy them. Take the kids, enjoy the serenity, look for little critters like dragonflies, note the colours and textures of the plants, and appreciate their gentle beauty.

MP: Join the National Wetland Trust and connect with a community conservation group restoring a local wetland. If you’re a behind the scenes person, then writing submissions is one way to help. You could also contribute to fundraising efforts or managing volunteers for a local community group.

Alternately, if you’re someone who jumps in boots and all, then helping to tackle weeds, control predators and plant natives are all needed to restore wetland health. There’s also monitoring – some methods to measure environmental changes in wetlands are designed for people without a science background. Check out the Wetlands Monitoring and Assessment Kit, and the Auckland Community

Ecological Monitoring Guide. Karen and I developed both resources, so we know they’re great! Tell us about the project you are involved with at Rotopiko in the Waikato.

KD: Rotopiko is a peat lake that formed at the end of the ice age, so she’s got some impressive age on her. The National Wetland Trust has been working with the local community to restore the site and create visitor facilities to enlighten people about the special values and mysteries of wetlands. It’s where the trust is planning to build a National Wetland Centre.

Already there is an outdoor family-fun trail for kids of all ages to enjoy. It includes a floating pontoon with wetland-themed panels, boardwalks through towering kahikatea trees and around the lake margin, and games along the way. Mudfish Scrabble anyone?

MP: I moved to the Waikato in 2005 to coordinate an experimental project at Rotopiko – seeing if a unique, threatened plant species (giant cane rush, which only survives in two small pockets in the Waikato), could be propagated and replanted next to the lake. These rushes help form peat, creating a carbon sink over many, many years if undisturbed. Spool ahead to 2022, and some of the original rushes have survived as has their passenger – a quirky moth with a super-skinny larva that lives inside the plant stems. Are we making progress with caring for wetlands? What more needs to happen?

KD: Wetlands have just been given extra strong protection at the national level through laws enacted in 2020. Yet already the government is under pressure to weaken them from certain sectors.

But the very fact the government was bold enough to pass these laws is a sign the New Zealand public and policymakers are now appreciating the vital importance of wetlands to our own health and wellbeing, for clean water, for carbon uptake, for housing many of our most unique threatened species.

We need to learn more about the role of wetlands in the carbon cycle, so those who protect or create wetlands can be rewarded with carbon credits, and those who continue to drain them pay for the environmental cost. We also need to look at more wetland-friendly agricultural practices, and again

Māori have knowledge that could help us re-wet drained peatlands and sustainably harvest valuable species from them. There’s a little section in the book on this practice – it’s called paludiculture and could be the way of the future for our sinking, drained Hauraki and Southland plains.

MP: The research carried out by the scientists featured in Life in the Shallows has provided crucial information for how we can better restore, manage and protect wetlands in Aotearoa. Community conservation groups have also garnered significant experience and know-how for restoring wetlands.

The next step needs to be top down: leadership, commitment and resourcing from central government to protect and enhance what’s left, and importantly, to create incentives for turning drained/infilled areas back into the wetlands they once were.

Get involved with the wetlands

VISIT Add a wetland to your itinerary when you’re travelling around New Zealand, so you can fully appreciate the great diversity of scenery, wetland types, plants and animals our wetlands have to offer. Find a wetland near you by visiting the National Wetland Trust at wetlandtrust.org.nz – the trust has a directory of wetlands to visit, ranging from wetlands right in the thick of our cities to more remote sites.

VOLUNTEER There are several wetlands where you can stay or volunteer. Places like Matuku Link in West Auckland, Mangarākau in Golden Bay, Pūkorokoro Miranda on the Firth of Thames, Sinclair Wetlands/Te Nohoaka o Tukiauau near Dunedin, Ōruapaeroa/ Travis in Christchurch and Rotokare near New Plymouth.

Life in the Shallows by Karyn Denyer and Monica Peters

(Massey University Press, $65).