The work of an architect requires many skills: there’s practicality — mathematics, science and engineering — required to manifest a successful building. And then there’s the creativity needed to cultivate beauty, innovation and originality. Add to that knowledge of construction, climate challenges, economics, geology, urban design, even weather patterns, and creating a building that is significant is no mean feat.

For Beth Cameron, one of a handful of female architects whose buildings were recognised in the recent New Zealand Architecture Awards, architecture is also about understanding people. “Architecture ultimately improves people’s lives and wellbeing,” says Cameron, co-founder of Makers of Architecture. “Form and scale can have a lasting effect on health and culture.”

Kirsten Matthew sat down with three of the award-winning wāhine toa to talk about their careers in architecture, their ethos’, and how they are redefining our built environments.

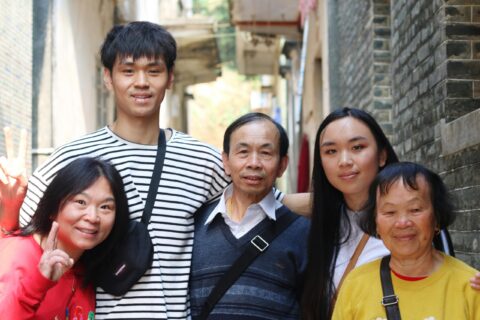

Caroline Robertson

As a co-founder of Spacecraft Architects, Caroline Robertson celebrates simplicity.

“You can do such beautiful work with simple, normal building elements,” she explains. “I can understand wild designs, but I like to think about how we can improve a building, looking at what clients really need, what will make the most difference by doing as little as possible.”

It’s a philosophy that can be seen in Spacecraft’s Pōneke Wellington co-housing project, Block Party, which won a Housing — Multi Unit prize at the recent awards. Described by the judges as “an exemplar for increased density in our cities”, it includes four homes that house six friends.

“Cohousing is complicated in its own way, but it’s healthy and really nice to have a social framework around you that isn’t total isolation,” says Robertson. “You can allow for interaction and that psychology is quite central to what I’m thinking about at the moment.”

It’s a way of life that Robertson, her partner Tim Gittos and their children enjoy themselves, living on a section with two houses, the second owned by friends. It’s not exactly co-housing, but it is a dream arrangement: Robertson drops all children to school in the morning, and the neighbours bring the kids home. She and Gittos share work and parenting: While they both design new homes, apartment fitouts, even a marina at the moment, Robertson is responsible for accounts, while Gittos takes care of client management.

Next year, the family are packing up and moving to Whangarei to build a courtyard house on poles with their own bare hands. “We get really involved in the process outside the architecture, so we know the risks worth taking,” says Robertson. “In Whangarei, building work will start early and finish early. Afternoons will be for admin, making sure our Spacecraft staff have client work to do, and so on. The process of building is so refreshing. It will be a nice counterpoint to designing.”

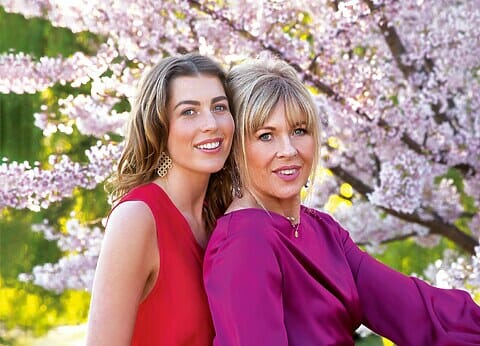

Beth Cameron

“It’s really about problem solving,” Beth Cameron says of her profession. “To design beautiful environments that are accessible to many through technological advancements, design and manufacture. Architecture definitely has a political element, too. It has a huge effect on cityscapes and the future of a place and its culture.”

As a co-founder, with her husband Jae Warrander, of Makers of Architecture studio, Cameron is known for residential projects that often feature pre-fabricated, sustainable materials. She established her business 10 years ago with friends. Warrander’s parents were their first clients. The practice has grown significantly in the last five years, with six staff now supporting Cameron in her work. A construction arm of the business, Makers Fabrication, has split off from the studio, and employs more than 20 people.

Cameron, who recently had her first child, takes care of design, client liaison, new enquiries and social media and marketing. “Jae and I seem to work together really well; it’s easy,” she says. “We’re lucky. We have different strengths but shared values that have held the company together.”

Their most-recent award-winning project, a tasting room at Ata Rangi winery in the Wairarapa, was conceived to support social interaction, raise awareness of the wine making process, and pay homage to the existing buildings and people who work in them. The awards’ jury described it as an “elegant, superbly executed building”.

“Wellbeing and health is an ingredient that has disappeared in many built structures, but it’s important,” explains Cameron. “Sensitivity to light and environment, how people will interact with each other, how it physically positions them, are all important things.”

Colette McCartney

For Colette McCartney, it’s co-design with mana whenua that makes her architecture fulfilling. It wasn’t always so: after studying architecture at University of Auckland, she worked in Sydney, on interior architecture projects for Merrill Lynch, Reuters, and various retailers. In London, she worked for renowned architects Pringle Brandon, creating interior architecture for civic and commercial entities. There was no co-design in any of the work, but since returning home, McCartney has come to relish large, cultural collaborations.

“After 20-something years I’ve gone back to my whakapapa,” explains McCartney, who lives in Papamoa with her husband and two children and is director of interiors and fitout management at GHD Design.

With Whangārei Māori Land Court, Te Kooti Whenua Māori, which won a national Interior Architecture award, McCartney was part of the team that transformed an austere 1960s building into a civic space that sings. Designed as a gathering space with judges, rather than a hierarchical courtroom, it’s imbued with the principles of mahi toi (art and craft), ahi kā (continuous occupation), tohu (guidance), and whakapapa (ancestry). As Nicole Dannhauser, Project Manager, Ministry of Justice, says, “The outcome is a space that is welcoming, respectful and flexible.”

McCartney, who is on the board of the Designers Institute and is committed to increasing the numbers of young Māori in architecture and interiors, is now focussed on Tauranga Moana Innovative Courthouse, a huge civic project that will span years. “Projects like this — big, internal, interior architecture with a co-design aspect — are a dream for me,” says McCartney. “You have room to do unique things in one space. It is work that has meaning.”

Related Article: If I Could Change the World