Celebrated authors Patricia Grace, Becky Manawatu and Briar Grace-Smith kōrero about their writing and the importance of telling Māori stories.

Patricia Grace

83, from Hongoeka Bay

Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa and Te Āti Awa

Patricia (DCNZM, QSO) is recognised as the first published Māori woman author (though she disputes the title, as she believes it discounts the storytellers who preceded her). She’s a mother of seven – including son Himiona, Briar Grace-Smith’s former husband – and is a staunch advocate for her papakāinga.

Becky Manawatu

38, from Dunedin

Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Mamoe, Waitaha

Becky is an award-winning author whose debut novel Auē was the best-selling New Zealand book of 2020. She is married to Tim Manawatu and has two children, Maddox, 16, and Siena, 12. A former journalist, Becky is currently the recipient of the prestigious Robert Burns Fellowship, and is working on her next book, Papahaua.

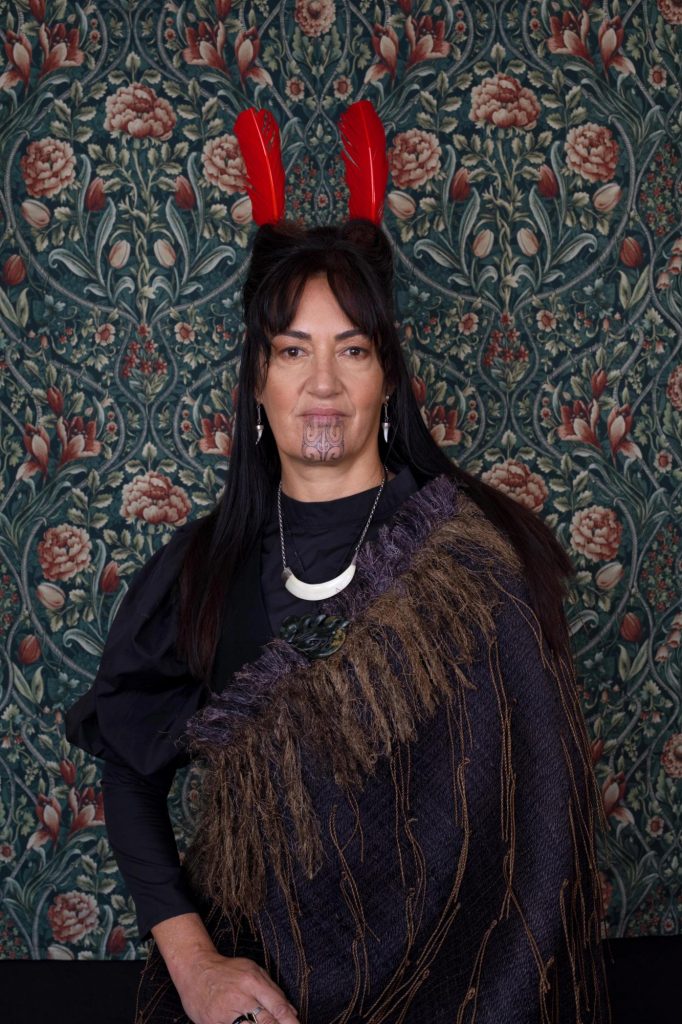

Briar Grace-Smith

55, from Paekākāriki

Ngāpuhi, Ngātiwai

Briar (ONZM) is an award-winning playwright, screenwriter, director and actor, best known recently for her film adaptation of Patricia Grace’s novel Cousins, which she co-directed with Ainsley Gardiner. She is māmā to four: Waipuna and Miriama, both 32, Himiona Jr, 28, and Mairehau, 16.

What’s better than talking to three of the country’s most celebrated wāhine Māori writers and creators? Getting them all together for a small wānanga, of course.

So that’s what we did, bringing Auē author Becky Manawatu to the Kapiti Coast to meet her literary idol, Patricia Grace, and her daughter-in-law Briar Grace-Smith – the woman behind one of the most pivotal films of our time, Cousins, based on Patricia’s hit novel.

We gathered over humble Thai takeaways in the name of Matariki to discuss everything from the life of a writer and what it means to be a Māori storyteller to the juggling act of writing, motherhood and more. It was a candid chat that was a privilege to witness as the artists shared struggles, laughter, advice and even book signings. Funny thing is, the last thing writers seem to want to talk about is writing.

Patricia: We never talk about writing, do we, Briar? We just talk about the family and everything else. It’s the same with any other writers, actually, it just doesn’t interest me to talk about it. That’s why I don’t think writing classes would have suited me.

Becky: I really wanted to ask about how you [Patricia] started writing, because you once said you started out just because you were asked to?

Patricia: Oh, yes. First of all, I’d had several stories published in different magazines. I belonged to a penwomen’s society and I started entering their competitions, and that was really good for me because it made me do something that I felt I wanted to try, and I don’t know whether I would have done, otherwise. I used to send them out, and I came to the notice of a publisher who wanted me to send them in for a collection. So I had an easy ride, really, into publishing and I’ve always been published ever since. I never had the struggle that I hear people say they have.

WOMAN: What about you, Briar?

Briar: My mum wrote children’s stories. She worked in preschool education and kōhanga, so I grew up being really encouraged creatively. I had a lot of books around me and she took me to plays, so I started writing plays first, when I was very young. She talked to me about how there were people on stage who were reciting words that had been written, and I’ll never forget her explaining that to me. I really liked the idea of having some kind of power and getting people to say what I had written. I was probably about seven or eight and my first play was in the cloakroom at school. Even now, it still feels like playtime.

WOMAN: How do you keep it that way and avoid it becoming mahi?

Becky: If it does [become mahi], it probably means it’s not going to be a very good piece of work. That’s what I feel like if I’m forcing myself to write something – that I’m probably stuck. But, I mean, I don’t know, I’ve only written one single book!

Patricia: That’s an achievement.

Becky: Some people have said to me, “Oh well, you might be a one-hit wonder.” And I’m like, “So what? It’s a book!”

Patricia: And no one can take that away from you. People actually say that? What a cheek!

Becky: I wanted to ask you, Patricia, about how you write when people are expecting something from you? How did you start your second novel? Was it hard?

Patricia: Well, no, because I thought I was just writing a short story. The first chapter, which became the prelude, was my short story. I had all these carvers surrounding me, so I wrote a carving story and then it was like, “Oh, there’s a house there – who belongs to that wharenui?” I started off with one character, and then Potiki was like that the whole way through; I didn’t know what was going to happen from one chapter to the next.

Becky: That’s a nice way to write, isn’t it? Because then you’re having fun and seeing something unfold in front of you.

Patricia: Yes. All my books are a little bit like that. The characters help me out, really. Once you get those characters, everything else comes.

WOMAN: So all the advice people give about planning and structure is a lie?

Patricia: I think that it is, for writers who are Māori. It seems to be more of a circular thing, like the film Cousins – it spins round and round.

Briar: I think it comes from whaikōrero and the way we tell stories on a marae. The speaker makes a point, but to make that point and to give it strength, they dance around all over the place, but still hold on to the nugget of what he or she is talking about. So I think that’s quite a natural form for us.

Patricia: Yes, and bringing humour and everything into it. All the things that make a good story come into that whaikōrero, because if they don’t, you won’t listen.

Briar: What we really grapple with in film is that for 130-odd years we’ve been told by white men in Hollywood that you write a film with a three-act structure, etc – and that is one way, it’s a valid way, but equally so is this other way of telling a story. I think the more stories we get out that take this form, the better. Things are starting to change in film. It’s been slow, but just recently, you can feel the change. We didn’t have a Māori woman direct a film for 30 years – isn’t that just ridiculous? And because we haven’t seen anyone working in that space, we don’t imagine it could be us. So we were all sort of colonised, as well, in terms of our thinking, but now we’ve had a couple of films break through that, and it just keeps happening.

WOMAN: Did you always set out to specifically tell Māori stories in a Māori way?

Briar: I mostly just write about what I know, therefore I write about a more Māori world. I write about experiences that I might not have been through, of course, but that I can kind of connect to and explore. I’m really inspired by Māori stories and concepts and art. I was a weaver at one point in my life, and the patterns and the concepts really informed my writing.

Becky: Again, Auē is my first book, but when I go back through my work that’s never, ever going to see the light of day, there’s a real mixture of Pākehā and Māori stuff and there’s quite a contrast within those stories. But I was always more drawn to wanting to write about the culture that I didn’t feel like I had enough access to.

Briar: Part of writing, too, is exploring and discovering – you get a chance to work out what the questions are that you have, about identity or whatever.

Patricia: Yeah, we’ve all done that. Like Briar said, you write what you know. And I felt as if I knew that world. I shouldn’t say that, because I was brought up in the city with my Pākehā mother and I knew which world I was in all the time. But the one that interested me was the Māori world.

Part of writing, too, is exploring and discovering – you get a chance to work out what the questions are that you have, about identity

WOMAN: What are your thoughts on other people telling our stories, particularly when there can often be a focus on gangs and violence?

Patricia: In the early days, when we were working on Cousins with Merata Mita, Once Were Warriors had come out and was doing well. So when we took Cousins to the Film Commission they’d say, “Well, where’s the conflict?” They were hinting all the time that it needed a bit more biff in there to make it worth their while funding.

Briar: I just don’t know why we have to keep perpetuating that. See, I believe we have some responsibility for what we tell and the way we tell it. We have a responsibility to our people. So I just go, “Walk away.”

Patricia: It even comes right down to advertising. I’ve been pretty annoyed recently with the ad that was made to persuade Māori to have the Covid injection. It starts off with a young girl with a very angry face and then it goes on to some women with boxing gloves, and then it ends up with a haka. To me, all they would need if they wanted to persuade Māori to have injections would be to get someone they respected having the injection or something like that, but it was all aggressive stuff. I saw another one done for the Pacific Island community and it was really nice – it came from within their culture and it had some dancing and other positive things, but the Māori one was just negative.

Becky: I feel awkward in the conversation because my book has gang violence and I have to take into account how responsible I should be. I still question my own rights to tell the story I told.

Briar: I don’t think Auē is a gang story. It’s very different. It’s your eye, it’s who’s looking in that matters. But yeah, we have to think about it, don’t we? We have to really think about what we’re doing. Everything is loaded and potentially political.

Becky: And it’s something that Pākehā don’t have to think about.

Patricia: I know that there are things I won’t write about. I’m not one of those who would hurt people, you know? I’m quite happy to leave out what I don’t think I should touch – I don’t have any reservations about that.

Briar: It’s really interesting – with film it’s visual, so there’s a whole lot of talk now about how we deal with this event in a way that doesn’t focus on the violence while still understanding it’s there. I’m interested in that now, too, because I’m tired of seeing violence. I’m just sick of it. Like Cousins, as a book, had so much integrity and the story was all about the gentleness in the storytelling and having these men who… None of them got any lead roles; they were just standing in the corner being supportive.

Patricia: Those are the sort of men I know – we grew up with men like that, like all those lovely uncles of mine. And that’s really important. Māori men get such a rough deal in the media, in books, in the news. I’ve got five sons and they hate it. Every time something happens, they feel it and it harms them. It takes you by surprise every time when it happens, having one of them say, “Oh, I hate that,” about something they’ve seen on TV, because you know they’re applying it to themselves.

WOMAN: How do you juggle all of that thought, responsibility and writing with the rest of your life and other mahi?

Briar: It is a bit exhausting. I was thinking about how there are no boundaries in my life. One aspect seeps over to the next quite often, and it’s just the way I’ve learnt to live – keeping super flexible. But it’s a real drive. If I go too long without writing, I get very restless. Patricia: Yeah, I sleep better, I eat more sensibly, all those sorts of things when I’m actually writing, so I just learnt to get on with everyday life really. As for the finance side of it, I had a husband who earned enough for the whole family, and I didn’t contribute all that much, and he was happy for things to be that way.

Becky: It’s awesome to have that support, eh? It’s so important – not that you have to have a partner, but that if you did, they’ve gotta come with the tautoko. For me, I just loved writing, so I just wanted to make it work. Ultimately, I think, love will make you do it.

WOMAN: Do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

Briar: I think that community is really important, so find your community, because it can be lonely. And if you can find your community, you can do it together, in a way.

Patricia: Don’t say, “One day…”. I know that I’m glad I never put it off. I had kids, I had a job, a house and family, no typewriter, no space of my own, but I’m glad I didn’t put it off. I’m glad I did it then. Because I could have very easily said, “Oh, when the kids have grown up…”, or, “When I’ve got a typewriter or an office…”, but the kitchen table has always been my place, really. That’s all you can do – just do it and do it your way.

Becky: I think, also, if you’re going to write fiction, falling in love with at least one character helps, because then you’re excited to be with them again and eventually that love grows and spreads to others.

Patricia: That’s really good advice. That’s what means most to me – the characters. Everything belongs to them.

I think if you’re going to write fiction, falling in love with at least one character helps, because then you’re excited to be with them again

WOMAN: And finally, how do you celebrate Matariki?

Briar: We never celebrated it, but about 10 years ago I was an object writer at Te Papa and they used to hold a lot of exhibits around Matariki, so I became more and more aware of just the idea of looking back and learning from it and moving forward. I also remember Patricia’s husband, Dick, showing me where the constellations were, and I was having difficulty seeing them, and he said, “We’ve lost our ability to see them.” And I’ve never forgotten that. He was describing it almost as if we had the knowledge, we knew where to look and how to see, and now we struggle with it.

Patricia: We certainly never celebrated it growing up, but we do now. We’ll have something at our marae every year for the children, go to the observatory. I also always think it’s a better time to have lights rather than at Christmas, when there’s plenty of daylight around.

Becky: It’s a way to brighten up the middle of the year when everyone’s kind of lumbering along, eh? I also didn’t know about it until my kids started learning about it at school. So now for me, I like to just set some… not goals – definitely not goals – but intentions for the coming year, and we’ll have a nice dinner together as a family.