Maybe there is the dance, as she says. Creation and change, destruction and change.

New marae from the old marae, a beginning from the end.

His mind weaves it into a spiral fretted with stars.

He holds out his hand, and it is gently taken.

It almost seems impossible that I should write of Keri Hulme. I have no special claim on her, and she is god-like in my pantheon – a wizard with words, weaver of magic – I had no idea what language could do until I read her. But then I did read her work, over and over, and that changed everything. She initiated me into the mysteries that words contain, the way meaning can be made from sound and rhythm and shape. As far as my reading takes me, I’ve enjoyed everything Keri wrote: her poems, short stories, articles, even online comments. If I didn’t understand or agree with something, I still enjoyed being in the company of her voice and her intellect: she has always shown me worlds and ways of being outside of my own. But it is The Bone People that changed my life profoundly.

I must have been 13 or 14 when I first read The Bone People, and everything about me was a bit wrong. My body was the wrong shape, my frizzy red hair was the wrong colour and style, I wore the wrong clothes because we didn’t have money, and I didn’t know how to talk to people, especially boy people. Normal teenage stuff, except that deep down I knew there was something about me that was a bit more wrong than other people. I didn’t have a mother, not one that I knew anyway, and my childhood had been pretty scary and lonely – I’d been miserable for most of it and was figuring out how not to be miserable as an adult. I don’t have any pain or blame left for the way things were but the reasons for it had something to do with domestic violence, mental illness and alcoholism. It would be a few more years before I would be fully free of the physical circumstances of that life, and I was still living with the duality that all children of fractured upbringings carry: trying to be “normal”, just like everyone else, while hiding the shame of what my life was really like. We are never fully free of our childhoods, and I eventually got to a place where I wouldn’t want to be – whatever deprivations mine held awakened in me a heightened awareness and love of narrative, without which I wouldn’t be who I am.

I think that its compassion for deeply damaged people is important; it gives space for readers to reflect on the pain in their own lives, including the pain they’ve caused, and to imagine what might bring healing.

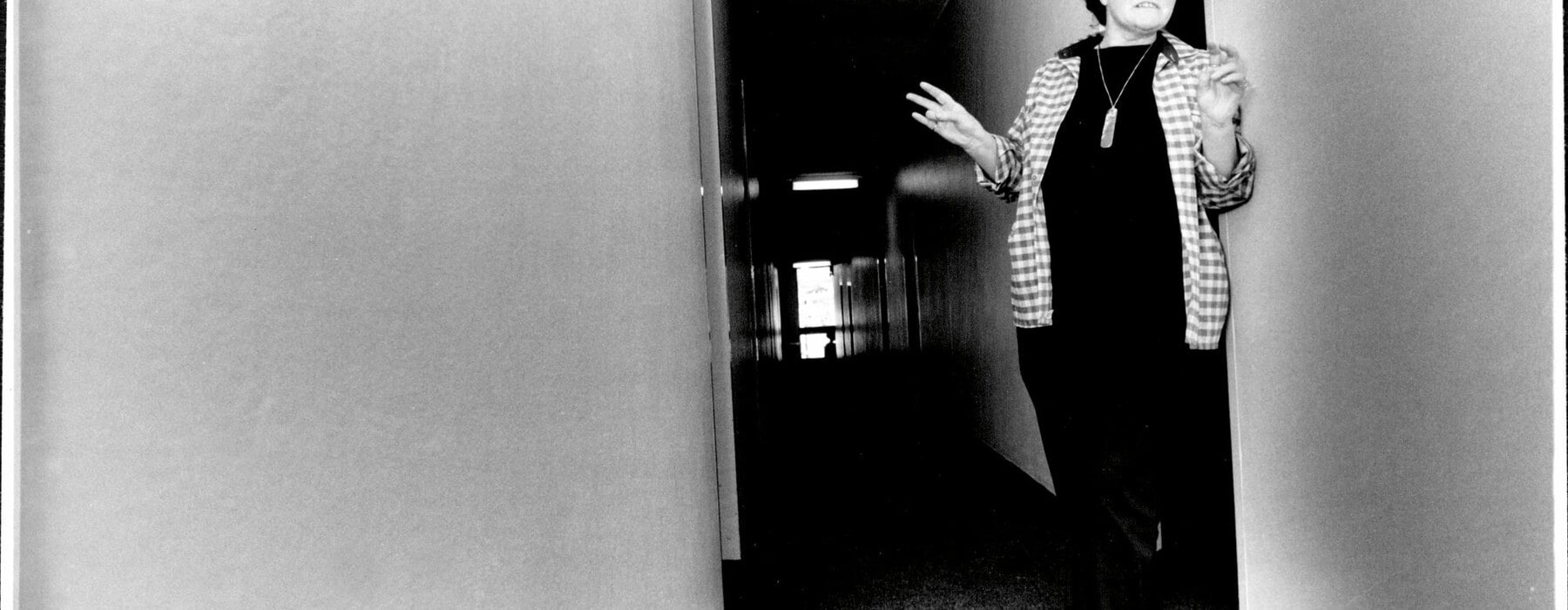

Marian Evans

Though I was mesmerised by its language and narrative power, I didn’t entirely understand the bone people as a teenager, so I read it again and again, each year shocked anew at my growing understanding. The poetry of Keri’s words called me in, and the mysteries of the story held me there, for no matter how many times I read the book, by the end there were no easy or complete resolutions to my questions. Perhaps mute foundling/non-Māori whāngai child Simon is the heart of the novel; his proud, damaged and violent, grieving Māori father, Joe, is the guts; and creative, independent, bicultural and asexual Kerewin, the eyes. The adults in the book are hard-drinking and unpredictable, much as the adults in my life were, but fortunately for me I’d never experienced the kind of physical violence Joe visits upon Simon.

What I did recognise was the psychology of that violence: the lies, the cover-ups, the shame, the loyalty. The way even the adults who see that something is wrong fail to do anything about it. The way we minimise our hurts and our guilt. How we pretend to ourselves and others that we are okay. I would get as angry at Kerewin for her silence as I was at Joe for his violence: how could she not do anything? Why were the adults in the book all so useless? Here is what I learned: people can hurt the ones they love terribly, and this will never make sense. The things I didn’t understand about The Bone People were as important as the things I did, because they introduced me to the important space in all good writing for not knowing. All around me, in real life, things happened that were nonsensical and cruel. It was comforting to find this reflected in a book, and also to understand that the failings in my own upbringing weren’t for lack of love.

The Bone People – one of my all-time favourite books. Booker-winner 1985 but the critics were dismissive; she didn’t belong to their literary club. It was an outsider story told by an outsider in an outsider way.

2019 Booker Prize winner, Bernadine Evaristo, Twitter

I want to say something about the legacy that writers leave for each other – the permission they give when they break the rules. Keri gave so many of us permission and her legacy wouldn’t exist without the feminist publisher Spiral Collectives who first published The Bone People when others refused to. I was never more aware of the Spiral Collectives’ part in things than when, after Keri’s death was announced, voices from all over the world poured their chorus of memory and mourning into the digital ether, sometimes at original Collective member Marian Evans’ request.

I first met Marian in 2009 when we were both studying towards a PhD in creative writing. A humble, gracious and incredibly supportive classmate, I was astonished when I learnt of her place in such significant and staunch feminist and literary history. I never imagined I’d find myself a “peer” of such a person. But of course it made sense – Marian remains indubitably supportive of creatives like Keri and is still an active member of current Spiral Collectives, which also included the late Irihapeti Ramsden and Miriama Evans. Since Keri’s passing, I’ve realised I should have talked to her about all this long ago, but thankfully Marian and others have written extensively of the Spiral Collectives online for anyone who cares to learn more. The significant grassroots work of women working collectively outside of the establishment continues.

That I have written three books is a miracle made up of improbabilities that were made possible, in part, by the existence of books like Keri’s. The Bone People is a book about misfits written by a misfit – I mean that in the most loving, admiring way of course, “misfit” being exactly how I would describe myself and most who are dear to me too. We who do not fit. We who must find new language to describe the worlds we inhabit, since those worlds defy the acceptable and expected narratives. Keri knew exactly what she was doing, steeped as she was in two literary and cultural traditions; she knew the rules but she followed her own music. I took this lesson very deeply to heart even at 13, and read her more confounding lines with the kind of openness that allowed me to accept that even though meaning was sometimes slightly beyond my grasp, I could see something of the intent in the shape of the words, their placement, the spaces and shapes around them. As a writer I delight in getting away with breaking grammar or language rules in a way that reflects more accurately the music in my head.

Sometimes, as Māori writers, we feel like we have to be careful what we write because of what others will think of us, or because we somehow might fulfil the perceived expectations and biases of the publishing establishment to see certain kinds of stories about us — that is, our trauma narratives. Think of the popularity of Once Were Warriors. But I can’t imagine giving myself or anyone else any such rules about what we are allowed to write, and I somehow can’t imagine someone like Keri writing from a place of limitation or fear.

Our stories are what they are, born of our experiences and our imaginations, and our world is always sadder for the lack of them. I write for us, the damaged ones, the triumphant ones, the ones that, yes, survived some trauma, or are surviving it right now, as we are reading. Let them think what they like they will anyway. Let us write not into victimhood, but into the most expansive version of us we can imagine, even if we have to start by placing our damage on the page and working outwards from there.

If it helps, we can imagine an isolated kid as we write, the mute child who will learn to speak by our example. Sometimes the ones who have hurt us will find their way onto the page too, because their stories also tell us something about ourselves. Keri’s legacy gives us courage to speak the unspeakable.

But all together, they have become the heart and muscles and mind of something perilous and new, something strange and growing and great.

Together, all together, they are the instruments of change.

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, all passages in italics are direct quotes from Keri Hulme’s Booker Prize-winning novel, The Bone People.