Conflicted feelings about censorship became an exercise of introspection into one’s own work.

In January, a Tennessee school board voted unanimously to remove Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel, Maus, from its eighth grade curriculum, because of “objectionable words”. The book depicts Spiegelman interviewing his father about his experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. This book-banning made huge headlines and acts as something of an emblem for the current rash of US schools banning material which, as the Tennessee school board said of Maus, doesn’t represent the “values” of “local communities”.

The opening line of Emma Sarappo’s recent article in The Atlantic declares, “Book banning is back” and highlights 14 titles that are under attack – including Maus. Sarappo points out that, unsurprisingly, many of the books at risk of banning deal with “race and LGBTQ issues”. Watching these events unfold in the States from so-called “New Zealand”, of course, allows me an academic and possibly detached opinion – maybe I even get to be smug about our progressive land. However, book censorship is a big part of my reading and writing life.

Book censorship here is largely invisible, but currently 1300 books are banned or restricted by New Zealand’s Office of Film and Literature Classification. As a country, we’ve decided to give the responsibility of assessing the potential harm of books to this government body.

Of course, there are cases of other organisations making decisions about what to teach or stock or lend. One that hit our headlines recently was the decision by some bookshops to remove the work of JK Rowling from their shelves after the author made what I regard as hateful and untrue comments about transgender folk. Twenty years earlier, teachers at an Auckland school were banned from reading Harry Potter books out loud in class after a complaint about the references to wizardry and magic.

These examples represent different types of limitation to access. One, censorship, deems a book illegal, while banning or “cancelling” represents a group of people who wish to make a book unavailable even though it isn’t illegal. Banning and cancelling often have more to do with the author than an individual book.

What all these types of banning have in common, though, is the belief that books, as an artistic expression, are so powerful they can incite real life consequences. That is a powerful claim for black marks on a white page. As Cory Doctorow said at a Writers’ Festival event in 2018, the yoghurt we ate for breakfast is more alive than the characters we read on the page, yet they elicit so much emotion and thought.

Several times and even several times this year, I’ve had my mind, heart and maybe even my life changed by books. So, the debate is understandable. Often in writing circles we ask, “What can books do?” And censorship of books seems to reply, “A lot! And possibly – too much!”

In our present moment, the censorship decisions that make headlines are the ones that are divisive and rage-inducing. I think this means the debate about censorship is forced into quite extreme and binary terms, often framed as a moral stance of being either for unfettered artistic expression or for “the children”.

I think of it as a fight between “books have no real-life consequences” and “books are nothing but real-life consequences”. I find myself more and more in the murky middle ground of these two extremes. While I believe banning books like Speigelman’s is dangerous and ill-informed, I just can’t get both my feet into the “people should be able to publish anything and any limit on artistic expression is bad” boat.

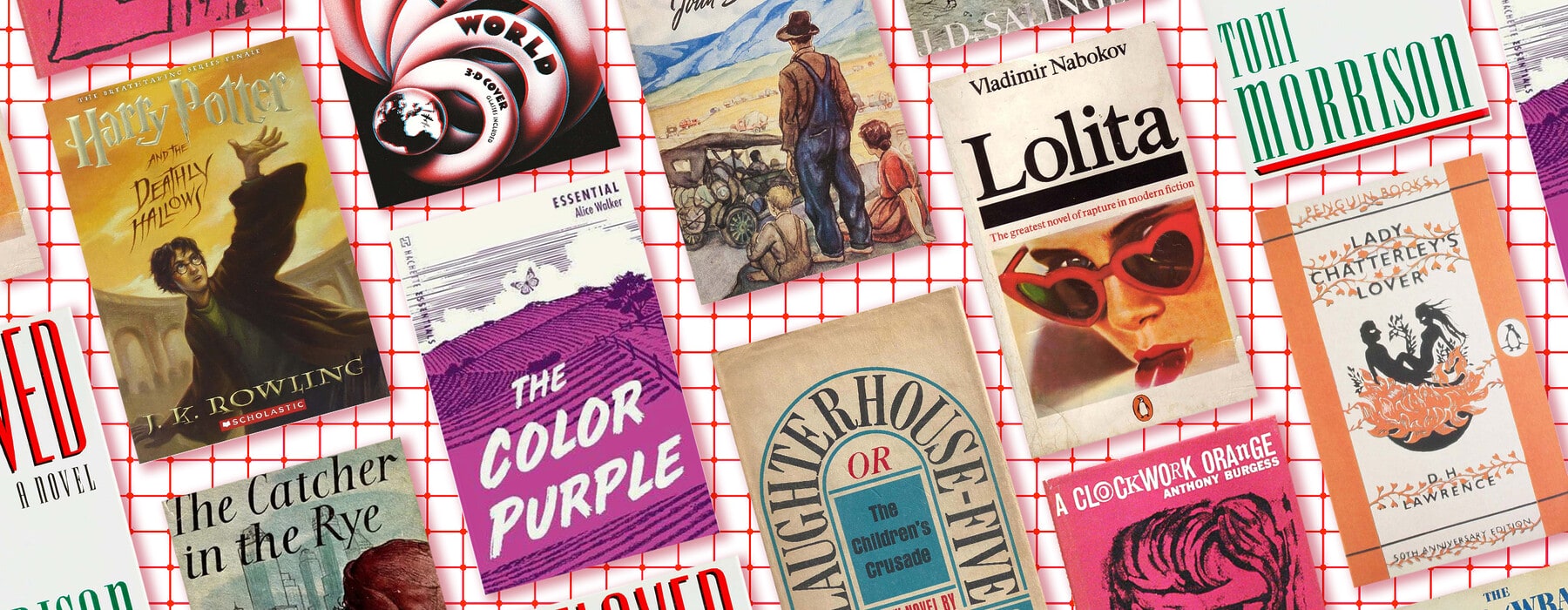

When I was 14 I read Lolita. I’d heard about it in The Police’s (equally dodgy) song Don’t Stand So Close to Me. Before Lolita I had read very few books, I was a naive reader – I read it uncritically as a love story. I think it had a big impact on the next 10 years of my life. I firmly believe Lolita was not safe in my 14-year-old hands.

A lot of years later, I’m not keen on the book – I kind of wish it hadn’t been written. Or perhaps, rather, I wish it would stop being canonised and celebrated. Or perhaps, I wish there were so many other books written from competing life experiences that it became obsolete. I believe just as firmly there are and will be 14-year-olds who will read Lolita critically and be able to challenge the ideas in it. I think a 14-year-old today is probably way more likely to be in that class. As young folk are more and more curating their cultural life through their phones – I believe there are far more savvy 14-year-olds than I was.

This experience, and the way I’ve thought about it over the years has made me think a lot about my responsibilities as a writer. After Lolita I read American Psycho, Last Exit to Brooklyn, Tropic of Cancer. I was obsessed with white dudes writing edgy books. My first writing is littered with me trying to shock in the most masculine ways I could muster. And in the back of my mind I’m sure I was thinking, I can write whatever I like! I can write as whoever I like!

But then something happened. I’m not sure exactly what it was but I think it had something to do with reading Janice Galloway’s The Trick is to Keep Breathing. A book that is truly shocking, but in all sorts of beautiful ways challenges the power structures of violence rather than reinforcing them.

I started to realise there is responsibility in writing – not a particularly popular idea until a few years ago. I saw that there was a different type of banning happening.

I started to think about all the books that never get written because of colonisation and rape culture and poverty. I saw that if my work was reinforcing these systems, then I was part of the problem. That a big part of my work is making room for these books. This often means getting out of the way – in a literal sense, sure, but also in an artistic sense – some stories are not mine to tell.

I find this the toughest part of this debate. Time and time again I see writers claim they’ve been “banned” or “cancelled” for appropriating a story that isn’t theirs, when in reality what they’re facing is criticism – an invitation to talk and learn. This minimises the very real danger of banning books like Spiegelman’s.

Today, I’m aiming for greater and greater self-censorship. I want to be thinking, What would this person think of this? How is me writing this limiting other’s right to expression?

And rather than approaching this as a moral problem, I’m thinking of it as an artistic problem – one that can help me write better work.