Teamwork makes the dream work for Mata Aho Collective, a group of talented wāhine Māori making waves in the art world. Dionne Christian writes.

Five artists walk into Bunnings in New Lynn, West Auckland, where they examine products like screen doors, insect mesh, rope, netting and weed matting a good deal more thoroughly than the average DIYer.

When they leave, they walk back to their Airbnb with rolls of mosquito netting and take steps toward making New Zealand art history.

Just three days before the country returned to lockdown, Mata Aho Collective – made up of Māori artists Erena Baker, Sarah Hudson, Bridget Reweti and Terri Te Tau – and acclaimed senior artist and weaver Maureen Lander were awarded the 2021 Walters Prize, worth $50,000, for their artwork Atapō.

It’s the first time a collective of Māori women has taken home the country’s top contemporary art prize, named after artist Gordon Walters and awarded every two years to recognise leading local exemplars.

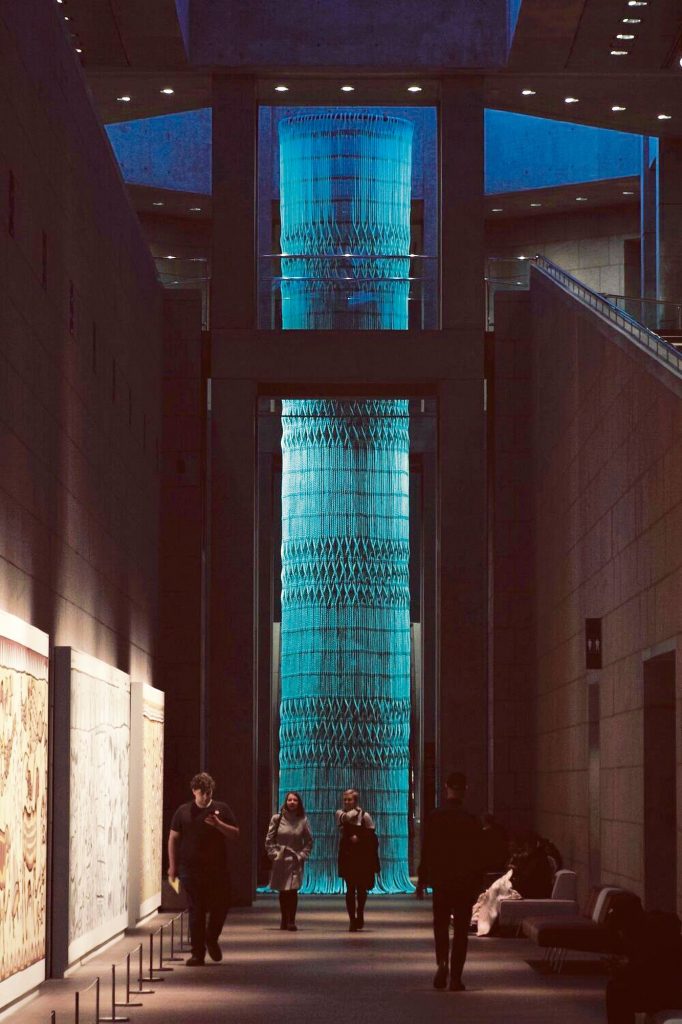

It is also likely to be the first time that an artwork made on the floor of a campground community hall has won the celebrated prize. Atapō (before dawn) was made in the hall at Pinewoods Motor Park in Red Beach, north of Auckland, partly because it was close to Maureen, but also because it was spacious enough to unfurl the nine-metre lengths of insect mesh needed to create an installation to span the full height of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Looking back, the women of Mata Aho smile at the memory of fellow campers walking through with buckets of freshly harvested mussels or politely reminding the artists that they would need to stop work because the hall was booked for a birthday party or church service.

In pictures of Mata Aho making their large-scale, fibre-based art installations, children are sometimes present playing on or beside pieces that will enchant, provoke and captivate audiences at museums and galleries around the world. Indeed, during our interview, Sarah holds Erena’s baby daughter.

Babies, beachside campgrounds and hardware stores are a world away from the images of spacious studios and rarefied galleries that a phrase like “contemporary art award” conjures up, but Mata Aho members bring a refreshing dose of reality to their work. This was noted by Kate Fowle, the New York-based director of MoMA PS1 and this year’s international judge for the Walters Prize.

Unable to travel to Aotearoa, Kate felt it was inappropriate to award based on a personal selection of one of the four finalists over another. Instead, she awarded the prize to Mata Aho Collective and Maureen Lander to celebrate “the inspiration they bring through their sustained collective practices, as well as for the potential futures they offer in their collaborative thinking and generative processes”.

“For me,” says Kate, “these qualities, together with the commitment the artists have to creating proximity, signal the work that needs to be done by all of us in the coming years, regardless of the barriers we encounter.”

With Mata Aho members living around the country and pursuing their own independent art practices, moments to meet and make are scheduled around work and family commitments, but when they get together, it’s time used well and thoroughly enjoyed.

“We have a lot of laughs,” says Terri. “When you get a bunch of women together lying around on the floor, there are a lot of silly stories shared! It’s the time when your hands are busy and we have nutted out what we are making. For all of us, the most favourite time is the making. You get in a groove and can chat about anything and everything.”

Atapō was commissioned for Auckland Art Gallery’s groundbreaking 2020 exhibition, Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art. Made from the insect mesh, wool, muka (flax fibre) and cotton, it references stories of atua wāhine (female Māori deities) Hine-tītama and Hine-nui-te-pō to explore the bonds of female collaboration and interconnectedness, the significance of lineage and the need to remember and honour this.

Taking on a commission to represent tīpuna atua as strong as Hine-nui-te-pō might have been overwhelming for one artist, but it was less daunting as a team, they say. Working as a collective makes sense given the complexity and diversity of the Māori women their art represents. As it says in descriptions of Mata Aho: “We produce works with a single collective authorship that are bigger than our individual capabilities.”

Being part of a collective also gives each one of them extra strength and courage. Coming out of their respective art schools as young Māori women taking kaupapa Māori art into gallery spaces – often a bastion of Western conservatism – was sometimes uncomfortable despite their confidence in and commitment to tikanga Māori.

“But if there are four of us, then we get to back each other and we get to be bolder, make bigger works and make bigger statements about being Māori in these spaces, so that other Māori – women in particular – can see that and aspire to go bigger, to go bolder and to take up more space,” Erena says.

“Being able to work with the women of Mata Aho and have so much trust in their conceptual or physical making makes me feel that we can achieve and tackle challenging topics, that we can dream big – as corny as that may sound,” adds Bridget. “But we’re not making work in a vacuum, so wider acknowledgements of those who have carved pathways before us, and also to the future generations, are important too.”

In 2018, the collective found itself facing the world’s media when Meghan, Duchess of Sussex visited London’s Royal Academy of Arts for its first exhibition dedicated to historical and contemporary Oceanic Art.

Meghan stopped to admire Mata Aho’s impressive 11-metre Kiko Moana installation which hung in the opening room of the exhibition and, based around the idea of a taniwha dealing with poor water quality in its home habitat, carried a clear environmental message. Rather than being dazzled by the duchess or the camera flashes, Terri immediately started to talk about climate change.

“I think it was kind of a good learning curve,” says Bridget, “because we never got any kind of media training, so we were figuring out what the media was interested in and what important things we need to have prepared to say when we do have platforms to speak. We kind of got straight in there and talked about climate change in the Pacific. It was only a very short time, but we knew we had to use it to say something important.”

The photos of Mata Aho Collective and Meghan found their way into newspapers and magazines around the world. “It was a way, I guess, for our wider family and communities, who are in the art world, to recognise what we have been doing when we go overseas and spend multiple weekends sewing tarpaulin…”

The quartet came together in 2011 at a rangitahi art wānanga (youth arts forum), which was followed by a summer residency from the Enjoy Contemporary Art Space in Wellington. Rather than make four different works to be exhibited in a group show, the art school graduates combined their talents.

The experience was so positive that Bridget, Erena, Sarah and Terri decided to get together to make work as Mata Aho Collective, and soon built a reputation for stunning and thought-provoking art made with an indigenous sensibility and a recognition that past, present and future are tightly interwoven.

They have worked with Maureen Lander since 2014, describing it as a tuakana-teina (mentor/mentee) kind of relationship.

“Maureen always says if you were a painter or a photographer and you had your work framed, you wouldn’t want another artist to come along and paint on your picture frame,” says Terri. “So, she’s thinking about the whole gallery space as framing installation work. At one of our first exhibitions, she said to us, ‘Is there anyone in the space close to you within your footprint?’”

Previously a senior lecturer in Māori Material Culture at the University of Auckland, Maureen says she’s comfortable working with younger generations and has mentored a number of artists and groups of weavers, but found working with Mata Aho particularly enjoyable, stimulating and challenging because of the way they work as a collective.

“They are all extremely talented artists in their own right, but when they come together they are able to achieve a ‘next level’ outcome in both scale and degree of complexity in their work,” says Maureen. “It’s been fascinating to observe how Mata Aho come together so well as a team – four brains and eight hands all in tune with each other.”

It’s been fascinating to observe how Mata Aho come together so well as a team – four brains and eight hands all in tune with each other.

And there’s lessons the younger artists (all born in the 1980s) can teach her, says Maureen, who’s been particularly impressed with the way they use social media.

“They use Instagram to post small snippets of the making and wānanga process which act like bait to intrigue their followers, who then can’t wait to see the finished artwork when it is finally exhibited,” Maureen says. “I could learn a lot from this as my own Instagram account is practically dormant! It is one of the main things I hope to improve on in the future after seeing how effectively it works for Mata Aho.”

A social media presence may have helped Mata Aho build an international reputation, but there’s no disputing the fact that the art itself is breathtaking. Kiko Moana, made from a light-duty blue tarpaulin that was folded, stitched and slashed, was originally shown at the German documenta contemporary art show in 2017 before travelling to Oceania.

In 2019, the collective exhibited Mahuika, made from red and yellow barrier mesh, wool and cable ties fashioned into ten hand-sewn pennant flags, at the Honolulu Biennial. Each flag represented the flaming fingernails of the Māori goddess Mahuika, who gifted knowledge of fire to her descendants.

Then there was AKA, created for the National Gallery of Canada – it was this installation that saw Mata Aho Collective first nominated for the Walters Prize in 2020. Completed, it stood 14 metres tall, weighed nearly one ton and aimed to provide “a space for contemplation” by inviting viewers’ eyes upwards to “places of raised consciousness.”

AKA – inspired by stories of the atua Whaitiri (the personification of thunder) – was made from stunning “Poly-Pacific Blue” rope found in a marine store in Honolulu, and was hand-woven in a 12 metre-high boiler room studio shared by Massey University volcanologists in Palmerston North.

Each project starts with a discussion about what they want to represent and how best to use materials – and their own artistic talents – to embody these ideas. Often, they don’t know what the finished art will look like, so there are experiments with concepts and materials, as well as the creation of small-scale mock-ups and models.

“Sometimes we say we’re engineers who went to art school,” says Erena. “There’s a lot of math.”

The materials they work with are selected partly because they’re the stuff of everyday life. “They are from our households, from our communities and they’re recognisable,” says Sarah. “If our whānau were to come into a gallery and not recognise anything else or feel comfortable with anything else, they would know what that material is, they would know what it feels like, they might have it in their house and might have found some ingenious way to use it themselves.”

The group’s shared hope is that by creating large artworks that take up space in a gallery and capture the attention of audiences, they will inspire other Māori artists to do the same.

“We come from a lineage of artists who worked to make space for us to get here and, hopefully, we do our bit for other folks to come up too. We want to push the boundaries of what’s understood and read as being Māori, Māori materials, modern Māori concepts.”

IMAGES VIA AUCKLAND ART GALLERY TOI O TĀMAKI AND MATA AHO COLLECTIVE