A revolution in the global jewellery industry emanates from a Wellington setting, writes Susanna Andrew.

I’d never seen a diamond in the flesh. Well, that’s not entirely true – I’d grown up with the sight of my mother’s gold band on her wedding finger. It was so familiar to me that when it was removed I couldn’t recognise her hands anymore, they looked bereft. The ring was very modest with maybe three tiny diamonds set deep into the slender band of gold, little chinks of light winking. My mother’s mother had given it to her because she was the only one of her sisters not to have been given a “proper” engagement ring. Let’s just say there really wasn’t much time between being betrothed to my father and being married.

Most of my mother’s generation were sold on the notion that diamonds – and only diamonds – were the symbol of enduring love; a promise of the heart. In 1992, an investigative journalist writing for The Atlantic uncovered a story of how an advertising campaign in the 1940s marketed an idea to drive growth in diamond jewellery sales for De Beers, a UK-based mining company which owned a diamond cartel in South Africa.

Giving diamond rings as a sign of engagement had been common since the Archduke Maximilian of Austria started a trend in Vienna in 1477 but by the turn of the 20th century the diamond ring had lost some of its lustre. Quality was poor, sales needed pumping.

The idea was very simple and surprisingly easy to believe. “Diamonds are forever”.

You couldn’t have asked for a better metaphor or a better marketing strategy. Co-opting the qualities of a stone formed beneath the earth over millions of years under conditions of enormous heat and pressure to suggest a romance that lasts a lifetime. Not only did the advertisers successfully sell the idea to young lovers but they upped the game and pitched it a second time as the gift of choice for a 60th wedding anniversary. And it didn’t end there, the “foreverness” of this ploy ensured diamonds were seldom re-sold or traded in. They were passed down and prized. These days the idea of diamond rings for engagement is not the expected tradition (well, let’s face it, getting engaged is not quite what it was either) yet still the idea of a ring holds sway.

Think of any diamond you’ve ever seen. They are always set in gold or silver, held by clasps, gripped by claws. Ian Douglas, jewellery designer and owner of The Village Goldsmith in Wellington, often heard from customers they wanted a ring with less of the wrapping. They wanted to see more of the diamond. For 20 years he worried away at the problem of how to better showcase these desirable stones, until he came up with a unique solution involving titanium and micro laser cuts. Ian worked with Callaghan Innovation and New Zealand Trade & Enterprise to launch the Floeting Diamond label in November last year. His revolutionary method has created a sensation in the jewellery industry worldwide and the interest has been global.

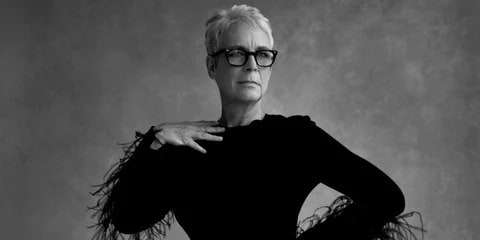

Take a look at our model on the cover and in our fashion shoot. Small schisms of light on her hand, in her ears and on a chain around her neck. Yes, they cost more than the car I drive but you can’t deny the dazzle and you cannot deny the beauty. Nuggets of trapped starlight. As Mae West once said, “Diamonds talk and I can stand listening to them often”.