Renowned Kiwi photographer Anne Noble is generating plenty of buzz with her recent work. She talks to Sarah Catherall about capturing the beauty of bees in her own backyard.

When Anne Noble placed beehives in her garden about 10 years ago, she never expected two things would happen: she would fall in love with bees, and would spend the next chunk of her life photographing them.

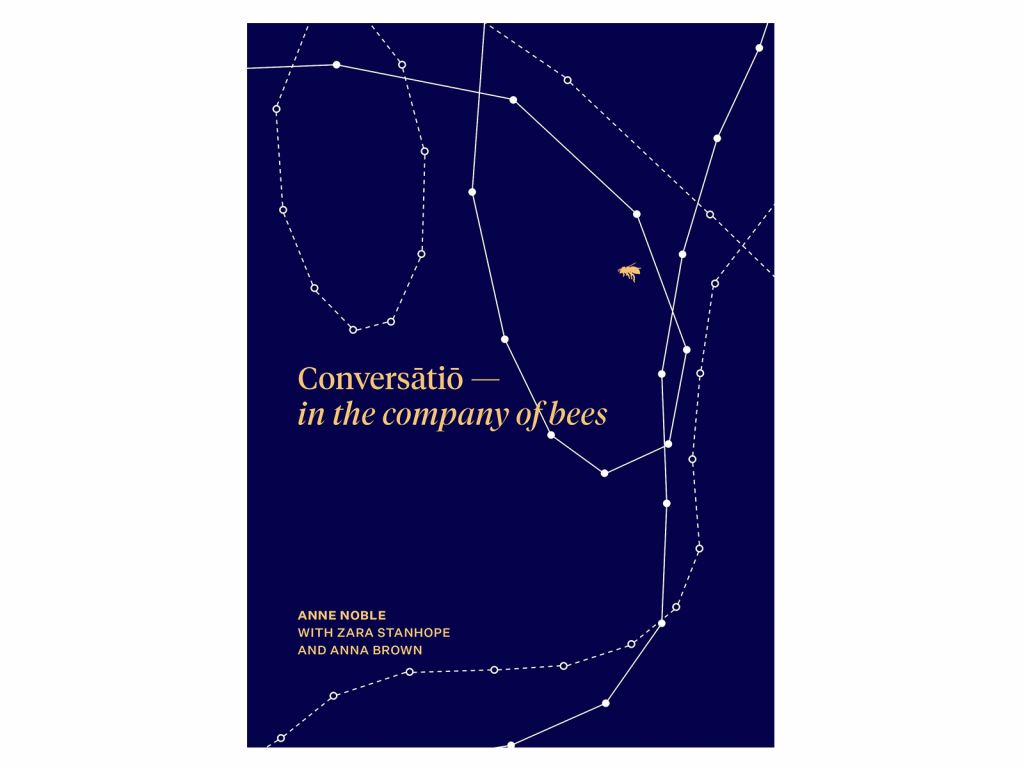

Now, the contemporary artist is about to launch a book containing her stunning, intimate and ethereal bee portraits: Conversātiō – in the company of bees.

Over the past four decades, Anne has become renowned for her striking, often haunting, images of the natural world, which help us understand it better. One of the country’s most respected contemporary photographers, the 67-year-old talks via Zoom in her home studio, surrounded by her black and white photographs hanging on the walls.

Anne nods that her bees are happy in their hives. She has already been down to check on them today.

Home is in Kelburn, where she lives with her husband, the architect John Gray. They have a daughter, Ruby, 28, who lives in Wellington and featured in one of Anne’s first photography collections, Ruby’s Room.

Being a beekeeper wasn’t part of Anne’s life plan. She explains, “About 10 years ago, our garden wasn’t doing so well and many of our fruit trees were flowering but not producing fruit. So, a friend suggested beehives. I expected John would look after them, but it turned out that it was me.”

Anne often went out in the evening to watch the bees flying home. Her artist’s eye would see the golden light catching their wings, and one day, she got her camera out and began capturing what she saw.

“I became fascinated watching them,” she says, her eyes shining.

The experience of watching bees was meditative. She had to slow down, to be still and to observe. “I was enraptured the first time they swarmed. I thought, ‘My God, the bees are leaving en masse!’

“There was a great swirling cloud of bees forming an extraordinary beautiful heart shape in the tree. There were 30,000 bees clustered around the queen… It takes you to think about the complexity of what you are looking at.”

Bees became such a passion that Anne also joined the local beekeepers club and began helping catch swarms. She collects honey from her hives and gives jars away to friends.

“I love looking after a colony of bees. It takes you extremely close to bees’ interactions with the world. It’s a wild system and as a beekeeper you have to create an environment in which they flourish. They’re completely independent of you, but I feel a sense of responsibility for the quality of their lives, their environment and the site created for them.

“Here I was falling in love with something which was at the bottom of my garden. I thought about how I could bring together these two things that I loved – being a beekeeper and an artist.”

Anne took that idea further when she got a Fulbright Fellowship and spent time at Colombia College Chicago in 2014, as its international artist in residence. While there, she met a local beekeeper who gave her a bag of dead bees which had been killed by pesticides.

Anne photographed their wings, and the result was a series of beautiful images, which also had an environmental message. She’s worried about bee health and that colonies are dying.

PHOTO BY ANNE NOBLE

“Bees are like a canary in a coalmine. Their health signals environmental damage,” she explains. “When industrial agriculture controls an area, bees suffer. Bees starve from a lack of food to forage on and they’re impacted by pesticides.”

Anne has exhibited artworks and installations about the honeybee in New Zealand, France and, most recently, with her work Conversatio: A cabinet of wonder, at the Queensland Art Gallery in 2018.

The latter was Anne’s most ambitious bee project – a “living photograph” in the gallery, where visitors could watch bees flying in and out of a glassed hive, and see Anne’s magnified image of a bee on the other side.

“Rather than being preoccupied with the death of a species, how could I make an artwork which was much more about life than about death?

“As the bees flew in, they cast moving shadows, so it was creating a living artwork. Then they would fly and disappear. So, people could sit and watch and wonder at this object which revealed itself. People could experience bees themselves as a work of art. There’s so much you can do with photography, but that pales compared with the experience of watching bees themselves.”

Since the early 1980s, Anne has spent her career photographing the natural world. In 2001, she took her first trip to Antarctica, which she visited several times over the years, taking documentary- style photographs to reveal how the icy continent is portrayed in popular culture, exploring how we have come to see Antarctica as “a glistening white world where penguins frolic and snowflakes fall”.

Her art practice has an intelligence to it and she has passed her knowledge on to the photography students she taught at Massey University, where she was a distinguished professor, a role she retired from recently after 26 years.

Her photography and curatorial work also reflect her interest in science. As a teenager growing up in Wellington, she aced school chemistry and considered becoming a doctor like her father. He was a surgeon and Anne often persuaded him to let her go into the operating room to watch him perform surgeries.

“I’m curious and fascinated by looking at things. Photography is part art, part science and part alchemy. You’re always using observational instruments but you’re seeing and imagining the world through technologies. There’s a lovely overlap between art and science.”

Conversātiō – in the company of bees is part science, part ecology and part art. Along with Anne’s photographs, the book contains essays by a bee scientist, an art curator and an art critic, as well as poetry and literature. It teems with Anne’s images of communities of bees, their translucent wings, photograms (cameraless images) of the wings of dead bees and a black and white series of electron microscope images. In all, her work shows the hive life of bees in rich detail.

On that note, the images hanging in her studio are not bee portraits as I first thought. Anne swings the Zoom camera closer to show her latest obsession: forests. Observing bees made her think about the biodiversity of forests, which are also under threat.

“It’s this idea that a forest is more akin or similar to a colony of bees than we perhaps realise. It’s finding ways of thinking about a forest as a system,” she reflects.

Later this year, Anne will exhibit her first images of tree trunks and forests, which she photographed around Wellington and in Whanganui.

As part of this project, entitled In a Forest Dark, the artist buried rolls of camera film in the forest floor and later developed the images. “I love the storytelling that takes place in the forest. I loved the Grimm fairy tales as a child. Forests are the space of the dark, the psyche, they carry wisdom. I think it’s important to imagine places with stories about them.”

Anne nods that, yes, for now, she is done with photographing bees. “I work on projects for about four or five years and then they reach some kind of conclusion. I’ve always enjoyed working on projects which have evolved over time.”

PHOTOS BY BONNIE BEATTIE, CHLOË CALLISTEMON, PETER MILES, ANNE NOBLE