With memories of being dragged to the theatre as a kid, Maria Majsa never expected to fall head over heels for a musical. Until she saw The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

My mother was tone deaf, bless her – she didn’t have a musical bone in her body. Though she listened to the radio, it was more background fill than act of commitment and she never bought records. She did have a favourite song – Moon River by Andy Williams. Sometimes she attempted to sing it while cleaning and, I’m ashamed to say, my brothers and I would gather like a wolf pack and howl to block out the sound. Yet somehow, despite contraindications, she loved musicals. West Side Story, Oliver, The Sound Of Music, My Fair Lady. One whiff of singing and dancing in a film and my mother hauled me off to it.

The first time this happened, I must’ve been about five. West Side Story was screening downtown, it was raining and we were late because of traffic. By the time we got to the St James, the only seats left were front row neck-breakers. Mum bought me a box of Jaffas, we sat down and I studied the ruched velvet curtains, feet swinging in space.

The house lights dimmed, the curtain rose, a hush fell and the assault began. Big shiny faces floated out of the dark like soap bubbles, bursting into song without warning. Women flounced in full skirts and men seized their shoulders and sang into their faces. I like to be in Ame-ri-ca. It was loud, it was hectic, it pinned me in place like a G-force test. Proximity of screen plus Technicolour Panavision multiplied by gigantic singing heads equals nausea. I threw up the entire box of Jaffas into a bin in the foyer afterwards.

Fast forward a decade to a sultry mid-summer evening in 1977. I’m on holiday, lying on a mattress with a handful of friends, wedged into the back of a lime green Falcon ute at a suburban Brisbane drive-in. We’re drinking, talking, waiting for the movie to start. The others have all seen The Rocky Horror Picture Show multiple times – I’m the only one with no idea what I’m in for. Thank god. Had I known it was a musical, I would’ve hopped on a bus and gone straight home. But I stay, and I learn something that night at the Keperra Drive-In (besides how to do the Time Warp). I learn that not all musicals activate my gag reflex.

Lush Man Ray lips drift on screen to sing Science Fiction/Double Feature and I sit up – suspicious, but intrigued. Several songs in and I’m finding the soundtrack pretty catchy – a mix of trippy tunes, ballads and ’50s bubblegum rock. Yes, the narrative is sketchy, but I’m not stopping to inspect plot holes when I’ve just been flung into the lair of a camp extra-terrestrial whose sole ambition is to fulfil his most outrageous fantasies. There are laughs and killer costume changes (notably Magenta’s goth-slut, French maid ensemble) plus fishnets, corsets and sequins. Conclusion: this film is a ride.

I don’t remember how many times I’ve seen The Rocky Horror Show since that night – I lost count after a dozen and the numbers aren’t important anyway. When I got back from Queensland, I dragged my friend (who hates musicals more than I do) off to see it at the Hollywood Cinema. Against the odds, she loved it too and that got me wondering. What is it about this goofy pastiche that strikes such a unique chord? Why has it become the musical for people who hate musicals?

Firstly, the energy couldn’t be more different to those white-bread musicals I’d been fed as a kid – no clean-cut Hollywood stars here, blinking into the spotlight while they belt out their big number. Rocky Horror clips along with a raucous authenticity I would describe as punk. It is inventive and funny with ragged edges that only add to its charm. Specifically, I love the moments of random weirdness peppered throughout the narrative – like the dusty half-eaten doughnut Riff-Raff fishes from his pocket to offer Janet bang in the middle of the Time Warp.

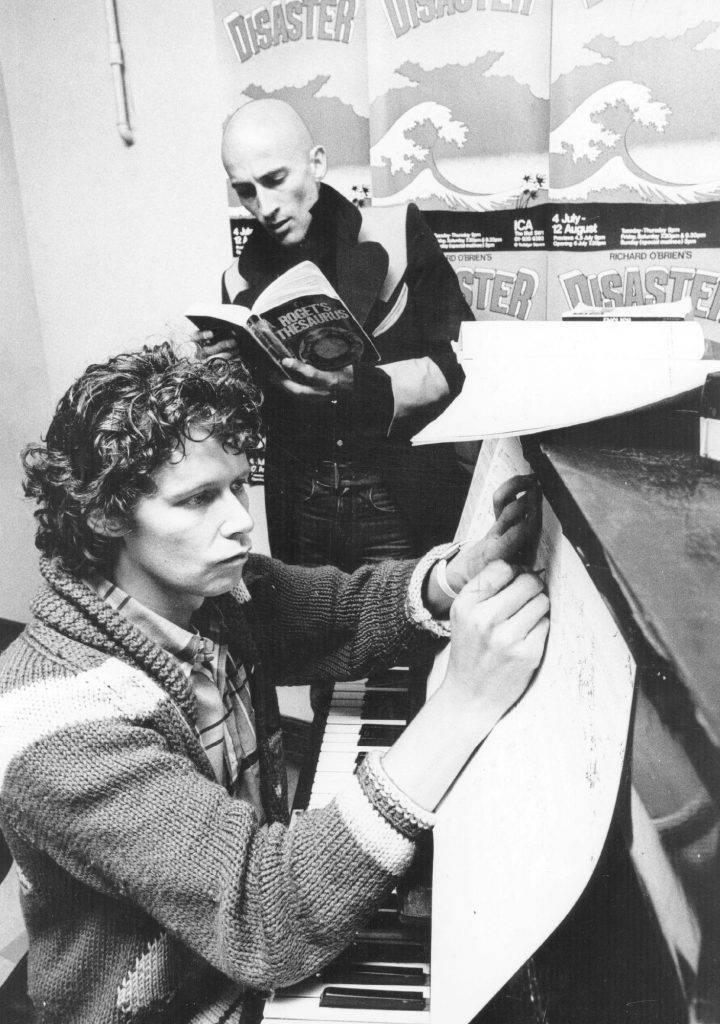

For the price of a movie ticket, you get a good jumble around inside the mind of its creator, Richard O’Brien, and let’s face it – there’s nothing like being invited into someone’s giant fantasy life. Aged six, O’Brien told his older brother he wanted to be a fairy princess. Sadly, or perhaps productively, he discovered this wasn’t something the world was ready to hear.

His glamorous longings turned inward and, like many a misunderstood soul, he went on to find his own means of comfort and escape. Much of his spare time was spent at the local cinema, where Hollywood B movies – sci-fi and creature features – fed his imagination. By the time he reached his teens, O’Brien had already laid the groundwork for the creation that would be the defining moment of his career.

Perhaps the coolest thing about RHS is the way it attained cult status in a seemingly effortless trajectory. O’Brien roughed out the plot plus a few songs in a lull between acting gigs. At the time he was aiming for nothing loftier than “building an entertaining evening that would make people laugh.” The play was an instant hit and enjoyed a long, successful run, but when the film version was released in 1975, it was a box office flop. The reviews were scathing. Mainstream audiences weren’t sure what to make of a movie where the all-American, straight, white couple were the freaks, while a gang of transgender aliens owned the show.

The film may have languished forever in obscurity, had a young film company executive not suggested late night viewings in art-house cinemas and college campuses across the USA. Midnight screenings began in New York at the Waverly Theatre just as the gay rights movement was starting to find its voice in the aftermath of the Stonewall riots. These late night sessions attracted a steady trickle of misfit followers who identified with the film’s gleeful disruption of stigmas and stereotypes around gender and sexuality.

Fans adored this movie. They wanted to live inside it, where they felt safe and seen. They started dressing as their favourite characters, in a sort of “shadow cast” and doing the Time Warp in the aisles. They threw props around on cue and invented dialogue to shout back at the screen.

Don’t dream it, as the song goes, be it. And behold, the first audience participation film was born. Word spread, audiences grew and the film went on to gross more than $120 million during its run as the longest theatrical release in cinema history. Not bad for a kinky little film about being true to yourself and letting your weirdness show.

Forty seven years on, O’Brien’s creation remains a cult phenomenon. The ongoing pansexual, gender fluid party he started has helped shift the dial on LGBTQI+ awareness and acceptance. And what of the man responsible for all this saucy nonsense? In 2012, O’Brien moved back from London and now resides permanently in New Zealand, where he is a bona fide national treasure with a bronze statue and everything.

On March 25, 2022, he turns 80 – another cause for celebration. On that date, which also happens to be my birthday, I’m planning a party. Covid permitting, I will hire out the Hollywood Cinema, dust off my fishnets and Janet Reger corset, raise a glass to Richard and screen the movie in his honour.

IMAGES VIA GETTY AND ALMAY