Foodies enjoy experimenting with the flavours and textures of different kinds of salt, but a health expert tells Sarah Catherall that whichever one you choose, it’s important not to have too much.

Salt is the main mineral in the ocean, making up three-quarters of the 3.5 percent of dissolved minerals in seawater. Salt also occurs naturally in mineral deposits, and this is known as rock salt. Because New Zealand has no rock salt deposits, salt was imported from the time of European arrival in the early 1800s until the country developed a sea salt industry in the 1950s.

Today, much of our domestic salt comes from Lake Grassmere, a 15 square kilometre lake near Blenheim.

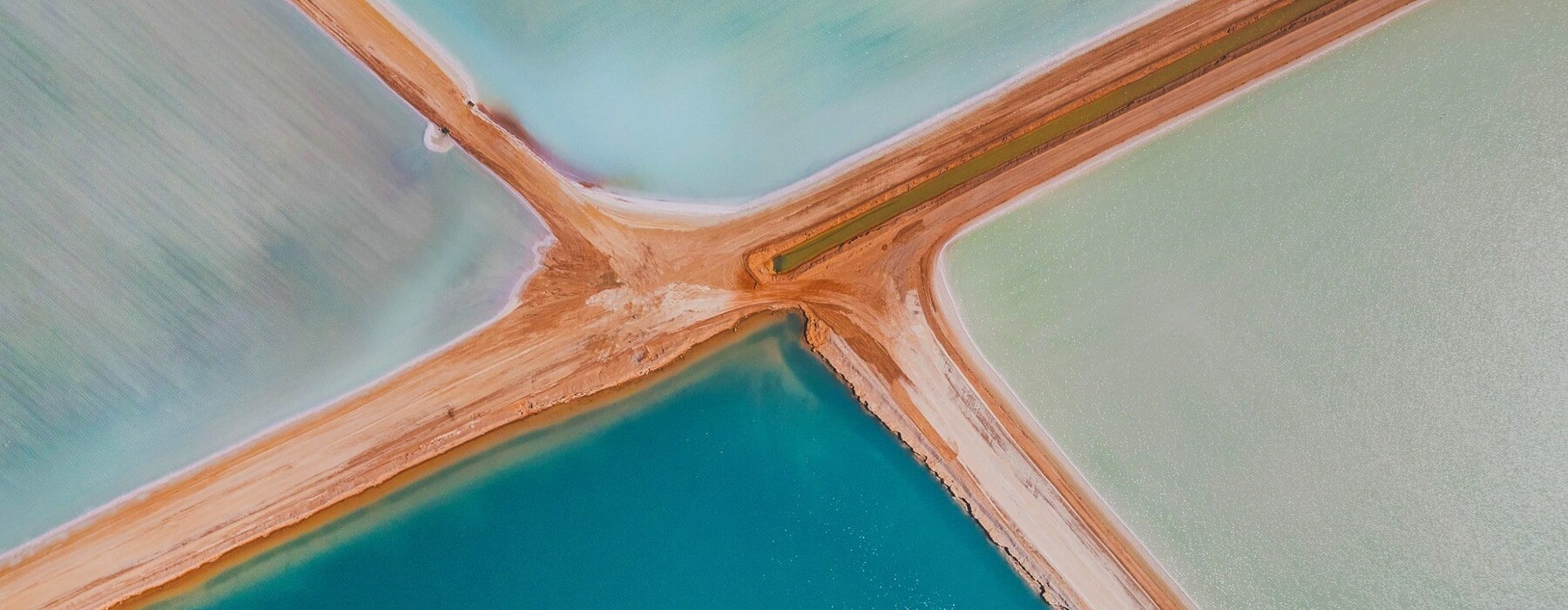

Seawater, fresh from the Pacific Ocean, is pumped into Lake Grassmere. Warm winds blow across the exposed lake, evaporating water and increasing the concentration of salt. The very salty water is pumped into deep holding pens, then into shallow crystallisation ponds. As the water continues to evaporate, salt forms as a crust on the bottom of the ponds. The remaining water is pumped out and the dried salt is harvested, crushed, washed in brine and moved by giant conveyor belts to form huge mounds of white crystals which are visible from late summer.

Salt evaporation ponds at Lake GrassmereImageMatt Ford from Dominion Salt says that once the salt has been harvested, it is washed using brine so it doesn’t dissolve. In some varieties, anti-caking agent is added to make it run smoothly, while iodine is added to some salts.

Matt explains the difference between table salt and salt flakes, which the company sells under its Marlborough Flaky Sea Salt brand. “To make table salt we crush large salt crystals to form small ones.

Marlborough Flaky Sea Salt is made using an entirely different process involving evaporation in an open pan. Flaky salt has an entirely different flavour profile compared with table salt. We also make a product called natural salt which has no additives and higher levels of naturally occurring minerals. But the more natural it is, the more likely you’ll see variations in moisture, texture and colour. Salt is naturally white. There is an urban myth that we bleach it, but that’s certainly not the case.”

He adds that “rock salt” is a label that is often used for marketing purposes when referring to coarse solar salt (where water is evaporated off by the sun). Because New Zealand is a young volcanic country, we have no naturally occurring underground rock salt deposits, so any authentic rock salt has to be imported.

While table salt may be too basic for chefs and foodies, chef Cherie Metcalfe says it’s best for baking as the quantities are easy to control. “You don’t want a lump of rock salt in your cake. Table salt dissolves easily,’’ she says.

Essential mineral

Cherie says salt is essential for the food rubs and seasoning products she creates. The Tauranga-based chef, who runs a food business, Pepper and Me, explains that her spice mixes, such as chipotle and lime salt, would taste “horrible’’ if the salt was removed.

Salt – that controversial mineral we are all told to eat less of – is the basis of many of her seasonings and food rubs. However, not all salt is equal, and like other chefs and foodies, she’s a fan of artisanal salts like rock salt, salt flakes and pink Himalayan salt varieties.

Cherie started her business about four and a half years ago, when her daughter, Pepper, was a baby. The former chef, who spent her pre-child career working in hotels, resorts and on superyachts around the globe, was playing around with a lactation-aiding salt blend to sell at markets. Her breastfeeding friends were making lactation spiced cookies, which were literally sugar, butter, flour and spices. “Some of the spices were really powerful and I mixed all these spices together with salt which people could grind onto food. So many people liked the taste and it was actually helpful with milk production, but most of my customers weren’t breastfeeding so they wouldn’t buy it.’’

Since then, she has expanded to offer a range of seasoning products, many of which form the basis of recipes in her new cookbook, Keepers. One of her most popular rubs, called Man Grind, is flaky salt mixed with chilli, lemons, herbs and garlic. Cherie says salt adds flavour to food. “It makes food taste good and also provides balance to a rub or a recipe.” Salt brings out the best flavours in the spices, she says.

Salt is also used to preserve food, and some cultures seem more comfortable using it. Cherie remembers eating cod in Norway, which was lying in a bed of rock salt before it was cooked and eaten. “It still had hunks of salt on it when we ate it. That’s not something you’d usually see here,’’ she says.

Cherie sources her sea salt from Maldon – one of the world’s most popular artisanal salt brands, which is harvested in the English town of Maldon.

Positively pink

Another salt growing in popularity among foodies is pink Himalayan salt, which comes as fine granules or rock salt formations.

In Auckland, the makers of Mrs Rogers, another provider of gourmet seasoning products, sell this pretty coloured salt. According to the product information, Himalayan pink salt is 100 percent natural, unrefined rock salt, mined in the Himalayan foothills in Pakistan. Said to be over 250 million years old and naturally pink in colour, the ancient salt bed is regarded as the purest salt on earth, uncontaminated by modern pollutants and toxins.

Mrs Rogers product manager Jono Steven says Himalayan pink salt is a premium salt and a pure, unprocessed alternative to refined white salts. It’s more expensive than typical salt, though, because of the costs of mining it and bringing it here. The flavour is similar to table salt, although some say Himalayan pink salt is milder and others suggest it has a sweetness which table salt lacks. It is dubbed as a “finishing salt’’.

However, Jono says it’s not correct to market it as mineral-rich compared with other salts. “While it does contain a full spectrum of natural minerals from the earth, and a little may be better than nothing, the amount is too small to significantly supplement your diet,” he says. Mrs Rogers doesn’t make any health claims in its marketing, “as excess sodium consumption is not healthy. We prefer to market it as an unrefined alternative to table salt, for those who prefer more natural products,’’ he says.

Jono says table salt is our most basic salt. “Table salt is raw sea salt that is sterilised and crushed to a fine granule, often with added anti-caking agent so it doesn’t clump, or added potassium iodide for iodised salt. It is produced in huge quantities; it is cheap to make and therefore it is cheap to buy on shelf, usually in basic plastic bag packaging to keep the price down.

Even Cerebos, another well-known salt brand, is introducing artisanal salt varieties. It says its Mediterranean sea salt is “hand-gathered from the waters of the Mediterranean. Our sea salt flakes are naturally formed into thin crystals with an extremely low moisture content, which makes it the perfect salt for the discerning chef.’’ Its Namibia salt pearls are balls of salt designed to be thrown into a pot of boiling water or crushed.

Cutting back on salt

While salt brands are expanding into gourmet varieties, they’re not making any health claims. Even the artisanal salt brands say that salt should be added to food in moderation. That’s a message Heart Foundation NZ is pushing. It says New Zealanders eat double the amount of sodium they should.

New Zealanders often don’t know they are eating as much salt (or sodium chloride, its scientific name) as they are, because it is added to everyday foods like bread, breakfast cereals and processed meats, according to chief advisor food and nutrition, Dave Monro.

Eating too much sodium can raise blood pressure, which is a leading cause of heart disease. The World Health Organisation estimates that high blood pressure is responsible for 17 percent of all deaths in high-income countries like New Zealand.

With three-quarters of salt added during the food manufacturing process, Dave says: “Most of us know that eating too much sodium [salt] isn’t good for our health, however many New Zealanders wouldn’t realise that we eat almost twice the recommendation. A big part of this is because it is hidden in many of the everyday foods we eat, like bread, sauces, cereals and other convenience foods. This again highlights the important role that food companies can play through the reformulation of processed foods,’’ he says.

Products like stock, soy and miso all contain hidden salt. The Heart Foundation advises that cooks should add flavour to meals by using herbs, spices, citrus (lemon or lime juice and zest), dressings and vinegar in place of salt. It also stresses we should check labels, choosing products which are low in salt or have reduced salt.

The Heart Foundation is working with food manufacturers to reduce sodium content in foods. So far, bread has 20 percent less salt than it had 13 years ago.

And while foodies are reaching for specialty salts, the Heart Foundation is against this trend. Says Dave: “The marketing of specialty salts, such as Himalayan rock salt or hand-harvested sea salt, can make them sound healthy. It’s recommended to cut back on all salt, regardless of type. It doesn’t matter how expensive salt is, where it is from, or whether it comes in grains, crystals or flakes – it still contains sodium.’’