Music has always had a propensity to provoke. But that’s where it holds its power.

Popular music is about – guess what – popular things; issues that matter to people. To slip past the powers that be, you need to speak in code, and if they’re not hip to the dots and dashes, it’s just an awful racket. The illicit, the improper, the controversial and even the downright dirty sneaks in under the radar and before you know it everyone’s talking about rock ’n’ roll and swing as if they weren’t once slang expressions for sex. It’s an eternal game of cultural Whac-A-Mole; stamp it out here, it pops up there, middle finger raised, and as this playlist shows, despite the best efforts of The Man, ageing busybodies and self-appointed censors, the music triumphs and endures.

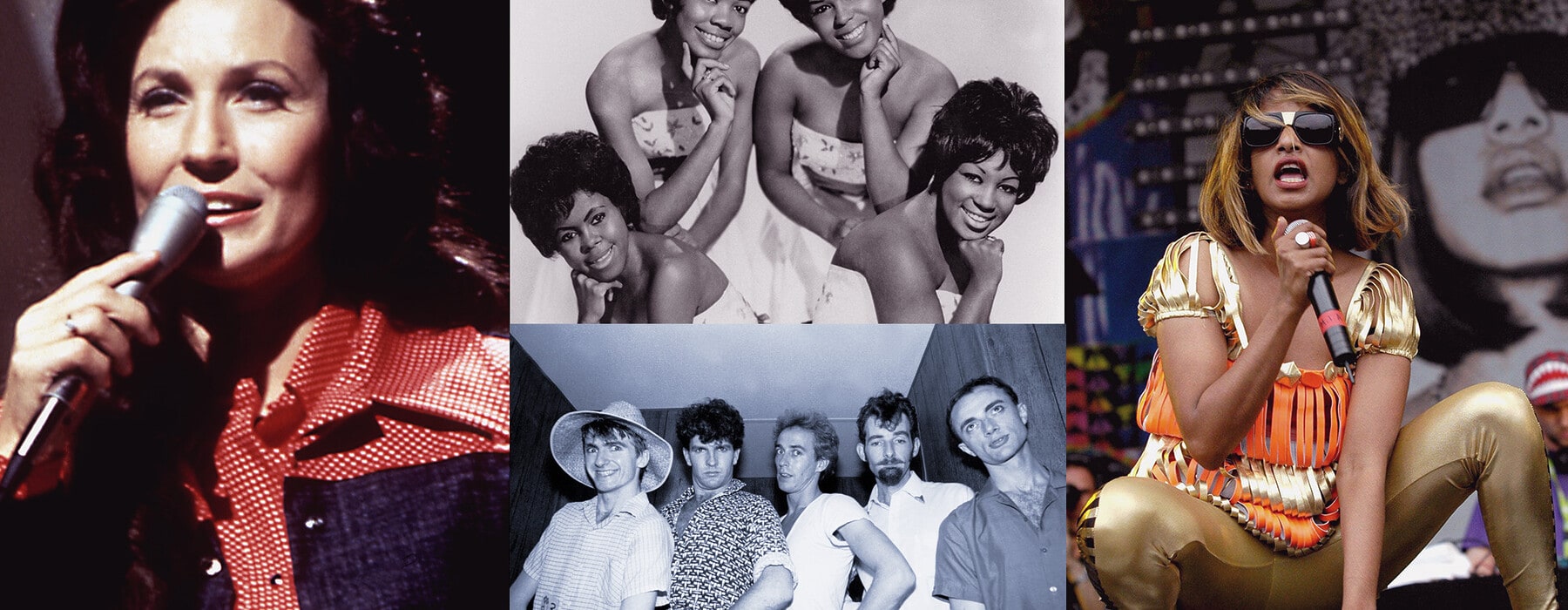

The most common bans usually concern the most popular musical subject matter – the ancient art of the horizontal boogie. Back in the innocent days of 1960, Will You Love Me Tomorrow, written by teenage newlyweds Carole King and Gerry Goffin and recorded by The Shirelles got itself banned for edgy lyrics like “Is this a lasting treasure, or just a moment’s pleasure?”. It might also have been the first record to turn notoriety into sales as the controversy made The Shirelles the first black all-female group to have a number one hit.

Cut to 1983 and Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s single Relax was not selling well at all until BBC’s Radio 1 jock Mike Read threw an on-air fit and refused to play it due to its “When you want to come!” chorus and tasteful tidal-wave sound effects. The Beeb doubled down, banning the song across its whole platform, including Top of the Pops. At the time, the band protested (perhaps too much, the naughty lads) that there was no sexual meaning in the lyrics, but since then have confessed that, yep, “really it was about shagging”. Before you knew it, Frankie were a global phenomenon. Thanks, Aunty Beeb! Where there’s muck, there’s brass.

Of course, when The Establishment was on the lookout for deviance they saw it everywhere. In 1963 The Kingsmen’s undeniably groovy tune Louie Louie was banned on radio due to a paranoia around the rather garbled lyrics. There’s a story that the record company, aiming for a bit of buzz, started a rumour that there was lewdness within. The FBI (obviously with nothing better to do) put a whole team on it and still failed to come up with anything incriminating. Meanwhile, the notoriety sent the thing to the top of the charts. Ka-ching again.

Possibly the most beige banning ever happened to The Kinks’ hit Lola in 1970. You might have expected the song’s awkward sexual reveal to have raised eyebrows at the time, but it was the Coca-Cola mention that violated the BBC’s strict ban on advertising in music. To get the song back on the radio Ray Davies changed one line from “She drank champagne and it tasted like Coca-Cola” to “cherry cola” and probably couldn’t believe his luck. Youthful pansexual enquiry? Go for it, team.

The contraceptive pill created another good reason for the Moralising Minority to get upset. Loretta Lynn’s The Pill made it clear that the Coal Miner’s Daughter (with six kids of her own) was retiring her broodmare status. Although released in 1975, the song still made conservative America’s hair catch fire and it got blacklisted by most country radio stations, with lyrics like “This incubator is overused/Because you’ve kept it filled/ The feelin’ good comes easy now/Since I’ve got the pill”. With nowhere to go on country frequencies the song jumped the fence and became a hit on mainstream radio, taking with it the good word on birth control.

What women choose to do with their bodies seems to always be upsetting someone. Cliff Richard, in a moment that seems beyond merely out of touch, released his 1975 cover of Honky Tonk Angel only to then discover the song was actually about a prostitute. Richard promptly demanded that the single be recalled in line with his strong Christian beliefs. Elvis, adept at balancing his spiritual and earthly appetites, had already recorded it a couple of years earlier.

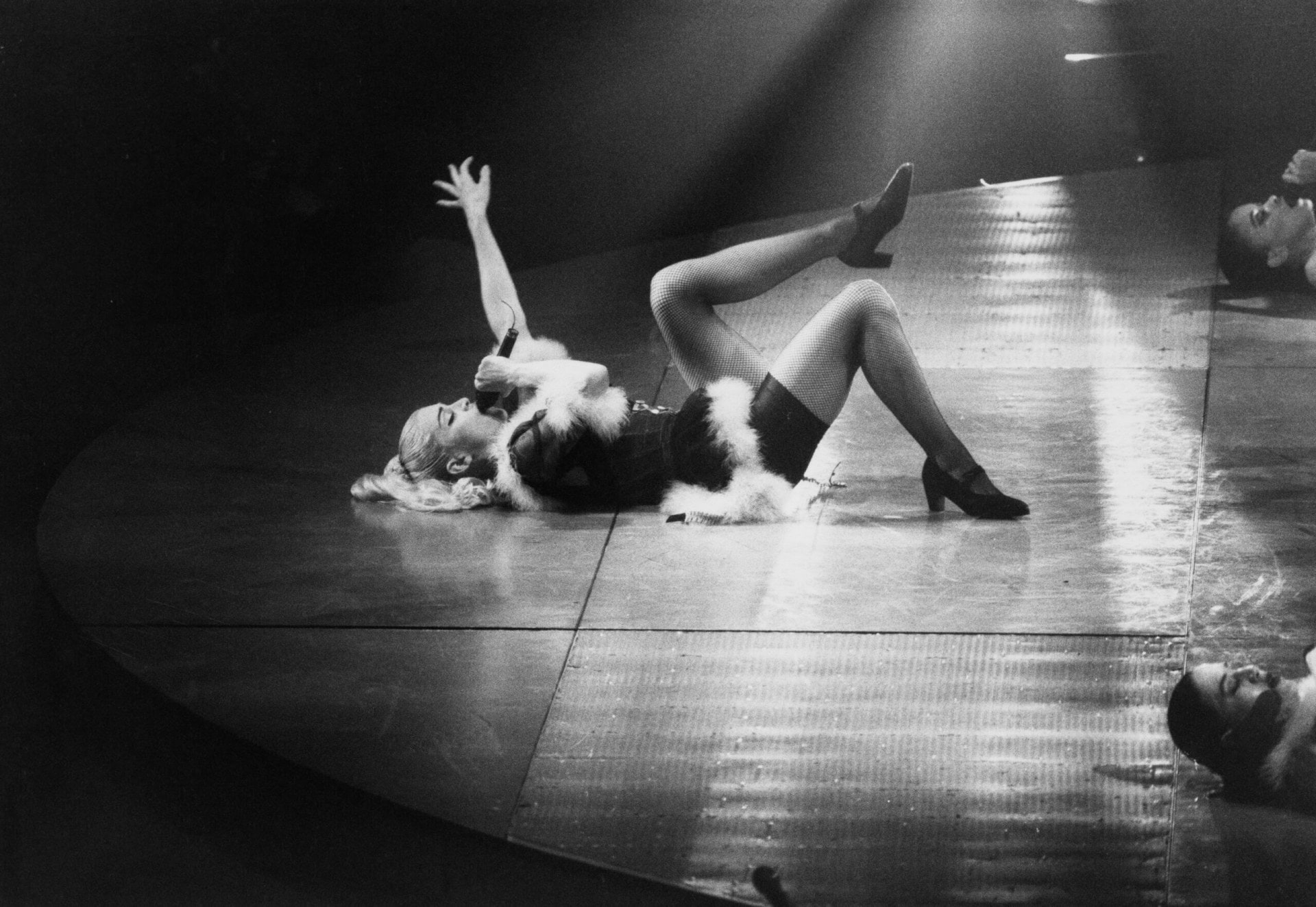

What’s great about popular music is not just the sex but the general, joyful vulgarity. Most of us have been told it’s not ladylike to have a filthy mouth, but the meter has run out on ladylike behaviour. So let’s go there, my bitches! The pre-eminent curse is undoubtedly the C-word, or See You Next Tuesday, or cunt. It’s what Julie Burchill called “the little black dress of swearing”, so whatever works for you. Some women are reclaiming it, some reject it as verbal violence, some can’t even say it out loud. Nonetheless, all must bow down in wonder at Ms Faithfull’s command of this and other top-shelf profanity in her tribute to sexual anger Why’d Ya Do It? from 1979’s smash Broken English. With lines like “Why’d you spit on my snatch/Why’d you let her suck your cock” the song was banned in Australia and removed from all local pressings of the album after staff at the EMI plant walked out in protest at its vulgarity. Because, er, Australians don’t like swearing, apparently.

Martha Wainwright’s sweary tour de force Bloody Mother Fucking Asshole is another song that you’re unlikely to hear on your radio. It’s a salty message for her neglectful father, ’70s singer-songwriter Loudon Wainwright III. Born into a musical tribe who processed their disputes in song, Martha honours the creative-family tradition that “everything is material”(ahem, The Mirror Book, Charlotte Grimshaw). Sadly, it’s not available on local Spotify but the cover by Miriam Bryant is faithful and you’ll quickly get the idea.

Another typical way to get banned is to insult the Almighty and/or his minions. Corseted agent of change Madonna has always had an extended middle finger on the cultural pulse. And 1989’s Like A Prayer distressed two unlikely bedfellows – the Vatican and corporate America. (Ms Ciccone happily juggles the sacred and the profane.) She enraged the Vatican with her subversion of Catholic imagery in the song’s video: variously the Madge+Black saint action, stigmata and a burning cross. Religious and family groups across America then boycotted Pepsi who had just used the song in an ad. The moral fallout forced them to cancel Madonna’s tour sponsorship and absorb $5m in sunk costs. Madonna – moving fast and breaking things long before Mark Zuckerberg thought of it.

This was not the first time religious groups had blacklisted an artist – famously gobby John Lennon opined that The Beatles were “more popular than Jesus” in 1966 and set off an orgy of Beatles LP-burning across the Southern US. These flurries of performative cultural exorcism amounted to not much but they made the righteous burghers of the Bible Belt feel good. And the kids always love a bonfire. Happiness Is A Warm Gun, off The White Album, was banned for sexual content but Beatles nerds remain in deep discussion about the song’s meaning due to its bewildering array of sex, drugs and guns imagery. I prefer the good faith interpretation that led to the Peanuts cartoon titled Happiness Is A Warm Puppy. WOOF.

If sex or religion is too easy, you can always try politics, or even war. War-bans are perhaps the most ridiculous in their overreach – during the Gulf War, ABBA’s Waterloo was taken off-air because it *checks notes* mentions a war. Following Margaret Thatcher’s death in 2013 the 1939 The Wizard of Oz song Ding Dong! The Witch Is Dead made a surprising return to the pop charts. Trying desperately to maintain decorum the Beeb banned it even though just about every other radio station played it. This stuff almost writes itself. When the Sex Pistols released God Save The Queen, it wasn’t the best of times in England, it was just the worst of times. Dubbed “the sick man of Europe”, mid-’70s England was mired in economic depression and the height of British engineering was the Austin Princess car. The song wrecked the Queen’s Silver Jubilee and was considered in “gross bad taste” by the BBC. That didn’t stop it selling by the truckload.

Even us inoffensive Kiwis got ourselves banned in 1982 when Split Enz’s Six Months in a Leaky Boat was whisked off the UK airwaves to protect the feelings of the Royal Navy during the Falklands War. Actually referring to colonial settlers’ voyages to Aotearoa, the song remains a beloved staple of homesick expat singalongs and intermediate school assemblies.

You can sidestep sex, religion and politics, but fun with drugs will always get the attention of the arbiters of what is good for you. The late Tom Petty, self-described “reefer guy”, had to remove a pretty harmless joint-rolling reference from his 1994 song You Don’t Know How It Feels to satisfy radio and TV networks. Obviously no one listened to the B-side of the single, which was a veritable laundry list of narcotics. Girl On LSD was so out-there that the record label wouldn’t have it on the excellent Wildflowers album. These days there are 18 US states that have legalised marijuana and the original version of You Don’t Know How It Feels will be playing to people who do, in fact, know exactly how it feels.

Gun references can also misfire. Young hip-hop star M.I.A. (Mathangi Arulpragasam) attracted the hairy eyeball of censorship when she released her 2007 hit Paper Planes. Parodying white middle-America’s fear of ethnic migrants, the song had its gritty gunshots and pot references toned down for TV (only proving her point further). In 2012 censors took Foster The People’s Pumped Up Kicks off the radio in the wake of the Sandy Hook school massacre, disregarding the song’s focus on teen mental illness and gun violence at a time when it was most needed. Two examples of a perplexing squeamishness in a gun worshipping society.

Rather than wait to get censored, Ice-T made his own version of the parental warning sticker on his 1989 album Freedom of Speech … Just Watch What You Say. He cautioned “Some material may be X-tra hype and inappropriate for squares and suckers” which turns out to be a fair warning.

Probably the most explosive of all taboos remains race. In 1967 interracial marriage was only just legal in the US – yes, you read that right – and 14-year-old Janis Ian recorded Society’s Child telling the still-feared tale of a white girl falling in love with a black boy. Radio stations were terrified to play it – an Atlanta radio station was burnt down after airing it – but the song eventually charted. In her autobiography, Society’s Child, Janis Ian describes audiences screaming death threats as she (still a teenager) was playing the song. Do yourself and Ms Ian a favour and go buy a copy of her self-titled 1967 album. Trust me.

Perhaps the grandmama of them all is when in 1930 Jewish schoolteacher and union activist Abel Meeropol wrote a startling poem called Strange Fruit – and he wasn’t talking about rambutan. Nine years later the poem was a song banned by radio stations all over the world for the crime of telling the truth. Sadly, while the music was stopped, the subject matter carried on regardless in the American South. The ban somehow made the song even more powerful – when Billie Holiday sang it live, she insisted on stopping the bar service so the image of “black bodies swaying from poplar trees” would have maximum impact on her mostly white listeners. In 1939 Time magazine dismissed the song as “a piece of musical propaganda” – fast forward 60 years to the end of the millennium and the very same magazine voted Strange Fruit the “Song of the Century”.

Change – it’s painful and slow. But there are weigh stations on the journey and at each place there’s a jukebox playing these songs.