New Zealand photographer Fiona Clark’s work has been both censored and celebrated. Now, a new documentary asks us to look at her images with fresh eyes. Sharon Stephenson writes.

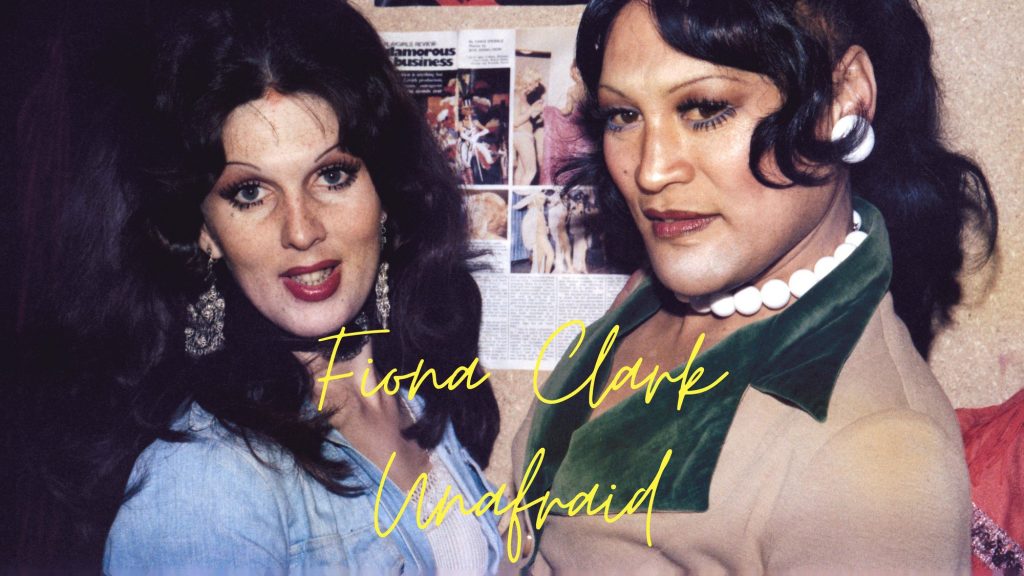

A hot summer’s night in Auckland, 1972. Drag queens stalk bars on Karangahape Road, all vertiginous platforms and backcombed wigs. Gay and transgender people also stare out from mostly black and white images, some grinning, others talking animatedly.

These images are the work of iconic photographer Fiona Clark, who has spent her career recording particular places and times in Aotearoa’s history.

In the 1980s, for example, Fiona’s camera gazed upon the lives – and tragic deaths – of people with HIV and Aids. Later, she switched her lens to New Zealand’s burgeoning bodybuilding subculture.

What her subjects have in common, says 67-year-old Fiona, is that they are the socially marginalised, the “freaks” and those to whom society isn’t particularly kind.

Her remarkable body of work is captured by the new documentary Fiona Clark: Unafraid, which premieres at this year’s New Zealand International Film Festival (NZIFF). In it, Fiona explores how scandalised the country was by her photographs of the early gay liberation movement in the 1970s.

“I wasn’t photographing these people because of their sexuality. I was photographing them because they were my friends,” says Fiona, who identifies as lesbian. “Even if no one got to see the photos, it was a record of who was there and what happened back then. It was a kind of validation and my friends loved the images.”

Sadly, others did not. Fiona’s images were censored and pulled from exhibitions, with numerous gallery owners refusing to work with her.

“You have to remember that being gay was illegal in those days. Some galleries had to put my images in a back office so that people could view them privately. In 1976, I had two works in an exhibition at Auckland City Gallery where the owner was threatened with prosecution, so he pulled the show. Those images disappeared and have never been found.”

Then, as now, it baffled the prolific Fiona, who believes strongly that contemporary art is about seeing things we might not be familiar with and challenging people’s existing views.

“I suppose it was the era, but people couldn’t understand or accept others who weren’t the same as them. For me, it was simply about holding a mirror up to society and trying to lift up the most vulnerable.”

So major was the fallout that when Fiona’s artist friend Tertius suggested she get out of town for a bit, that’s what she did, heading back to Taranaki where she was born.

Around the same time, the former Tikorangi Dairy Factory came up for a sale, which she and Tertius bought.

“It was cheaper to live in the country and, as artists, we didn’t have a lot of money,” says Fiona. “We made a garden and had chickens.”

Even then, the locals tried to stop “two hippies” buying the decommissioned factory. “We got around it by telling the council we weren’t hippies, but artists!”

The Auckland scandal followed Fiona to Taranaki, with some shops refusing to serve her, and her library card mysteriously going missing.

“I’ve never felt unaccepted by any of the communities I’ve been in except for farming ones, which can be pretty brutal, even now.”

Tertius eventually moved to Australia, and for the past decade Fiona has lived in the factory on her own – save for a Jack Russell called Meg and, until recently, a geriatric goat named Nancy Girl.

She’s spent those years slowly doing up the former manager’s cottage, turning the milking shed into a darkroom and filling the factory with art projects and collections of everything from vintage china to arts and crafts.

“I volunteer one day a week at the Waitara Project Recycling Shop so I find a lot of stuff. Actually, stuff finds me!”

In 1977, tragedy intruded on Fiona’s life when a drunk motorcyclist smashed through the windscreen of the car she was driving. Not only did she break every bone in her face, it left her with partial sight in her right eye, a head injury and numerous hospital stays.

Naturally, she picked up her camera to document her recovery, calling the series The Other Half. Focusing on trauma and blindness, the work was never shown in New Zealand, but Fiona was invited to exhibit it at London’s Raven Row gallery in 2017.

“The gallery curators heard about the series so came to visit me, and they flew me out to London for the opening.”

It was during one of her many hospital stays that Fiona found her next subject: bodybuilders.

“There was no physios back then, so I would walk around Auckland Domain to stretch my legs. I came across a gym where I watched people bodybuilding, which was new to New Zealand, especially women bodybuilders. I was fascinated with the gestures and posturing and the idea of being in control of your body. I’d lost control of my own body, which was probably why it appealed so much.

”Ask Fiona about her heartbreaking images of Aids and HIV patients and her voice catches in her throat.

“They were my friends and they were dying. The ’80s were brutal in many ways. They felt like a repetition of the hatred and bigotry of the ’70s.”

There was no real epiphany that set Fiona on the artist track. One of six children born to dairy farming parents, she grew up in Inglewood – not far from where she lives now – and from the age of 14, Fiona knew she was different.

“I didn’t fit the norm at Inglewood High School. Acceptance wasn’t part of the wider community for me growing up.”

Escape came in the form of “doing things”, such as painting, sewing and hammering objects in her father’s shed.

As soon as she was done with high school, Fiona jumped on a bus to Auckland with two suitcases and a curiosity that a small town couldn’t satisfy.

“I got a job at the hospital in the tuberculosis ward, but then someone told me you couldn’t work in that ward if you were only 17.”

She got accepted into Elam School of Fine Arts, where she initially studied sculpture before switching to photography. To help pay her fees, Fiona ended up working behind the bar of a waterfront café, which turned out to be the headquarters for those she later photographed.

“I was a wide-eyed girl from the provinces, but these people were friendly to me. I wanted to record us hanging out, going to parties and bars. I thought it was a world people needed to understand and that I could capture it.”

Fiona has never let her accident affect her ability to capture life, especially social injustices, with her 1953 Leica camera. She’s a staunch advocate for the environment, taking photographs of coastal resources that were used by local iwi for one of the first-ever Waitangi Tribunal claims.

The idea for Fiona Clark: Unafraid was floated three years ago by Auckland-based Argentinian director Lula Cucchiara, who spotted some of Fiona’s work in an art gallery. “Lula asked to meet me and said she wanted to make a documentary about me and my work.”

Along with an eight-day shoot with an all-women film crew, Fiona had to do a deep dive into her extensive photographic archive.

“I tried to contact everyone in those photos to let them know they would be used in the documentary. I had great feedback and people were pleased that I was telling their stories again.”

Fiona insists the documentary isn’t about her, but rather “a tough journey a whole lot of people have been on”.

“As the title suggests, we were unafraid of abuse and ridicule back then and I hope this documentary teaches people to respect history. Because it’s through our history that we can move forward.

Behind the lens with Lula Cucchiara

I was born in Buenos Aires and grew up in Córdoba. Fourteen years ago, at the age of 17, I decided to visit Aotearoa on a working holiday visa – the intention was to stay for a year, but I found my second home here.

I come from a creative family of photographers and film-makers, so that’s always been in my DNA. I like creating and making, I like real people and real stories. I’m always documenting, if not for a job then for friends and family.

I wanted to make this documentary because I believe Fiona needs to be recognised for all the work she has done documenting a massive part of Aotearoa’s history, whether through environmental changes or the LGBTQ+ community.

It was my first film, so every step was a challenge. However, I absolutely loved the process and wouldn’t change a thing. I can’t wait to make more!

I hope this film resonates with people, and helps them remember the images and appreciate Fiona’s work, and the time and years she has put into documenting such important parts of our history. I also hope we inspire others to be who they want to be, to trust their gut and keep going.