Mahsa Amini’s death at the age of 22, brutally beaten to death in prison for not properly covering her head with her headscarf in Iran has caused a storm of protest and hundreds of deaths. Worldwide the reaction has been outrage. Gilda Kirkpatrick reflects on an upbringing in Iran that has motivated her to lend her voice to a cause that is unifying millions, advocating to abolish a draconian regime that silences the voices of women. As she says, she is free and they are not.

The sound of a violin. A music lesson with a child in another room. The contrast between the lulling beauty of distant strains of music and the crackling intensity of Gilda Kirkpatrick is quite something to experience. She is a woman with a cause, and you cannot help but listen up. However, everything I see around me in her home seems to deny what she is telling me: the mansion on Paritai Drive overlooking Waitemata Harbour; the opulence of the spaces and grandness of the furniture; the gorgeous pets – a Maine Coon cat, an orange pointer; a bespoke aquarium complete with side plate-sized turtles; and a child, or possibly two, at King’s Primary in Remuera. This is the outcome of Iranian diaspora, and this is Gilda’s remarkable story.

She was living in Tehran and just turning 16 when it happened. The hijab control police arrived at a birthday party for a friend and arrested everybody in the house because it was a “mixed girls and boys” party.

“You know – teenagers with their parents,” she says. “They took us to jail and they kept us there without telling our parents [where we were] for a couple of days.” Then they were allowed to contact home. The teenagers were kept in prison for nearly

a fortnight.

I ask Gilda what happened while they were incarcerated.

“Interrogation, every day,” she replies with a groan. “Humiliation. It was just disgusting. Then they took us to – what do you call it? – a coroner – to make sure we had our virginity intact. Because if you didn’t there would be a second part where they have to find out who you had sex with, and either give you lashes or make you marry that person.”

Gilda and three other girls were identified as virgins and sent home to change their clothes and ordered to come back the next morning. The four girls were held in jail for a further three weeks.

“It was just after this period of imprisonment, in 1989, that I came out to New Zealand.”

For years after she arrived in New Zealand, Gilda flinched and gasped for breath whenever she saw a white SUV. That is what the hijab police drove, and anyone at any time could be taken away. Gilda describes her move to New Zealand as being like waking up from an amazingly peaceful sleep after nights of insomnia. But she also says Tehran has a population of 20 million people, and she spent a long time wondering where all of them were.

Although Gilda has escaped Iran, she says, “You carry it with you. You don’t stop thinking about the abuses or caring about the pain of people you have left behind.”

For Gilda, Iran has had two revolutions. The one she witnessed herself, as a child of six or seven years old, living in Tehran, and the one that is happening amongst young people today. The symbol that connects both these two epic periods of struggle is the scarf – or hijab – not just an emblem of faith and commitment to Islam, but a tool of civic oppression.

“When I take on a project, I do the research. Dig deep. Get the backstory,” she tells me. “People always want to simplify things.” And nothing central to people’s freedom is simple.

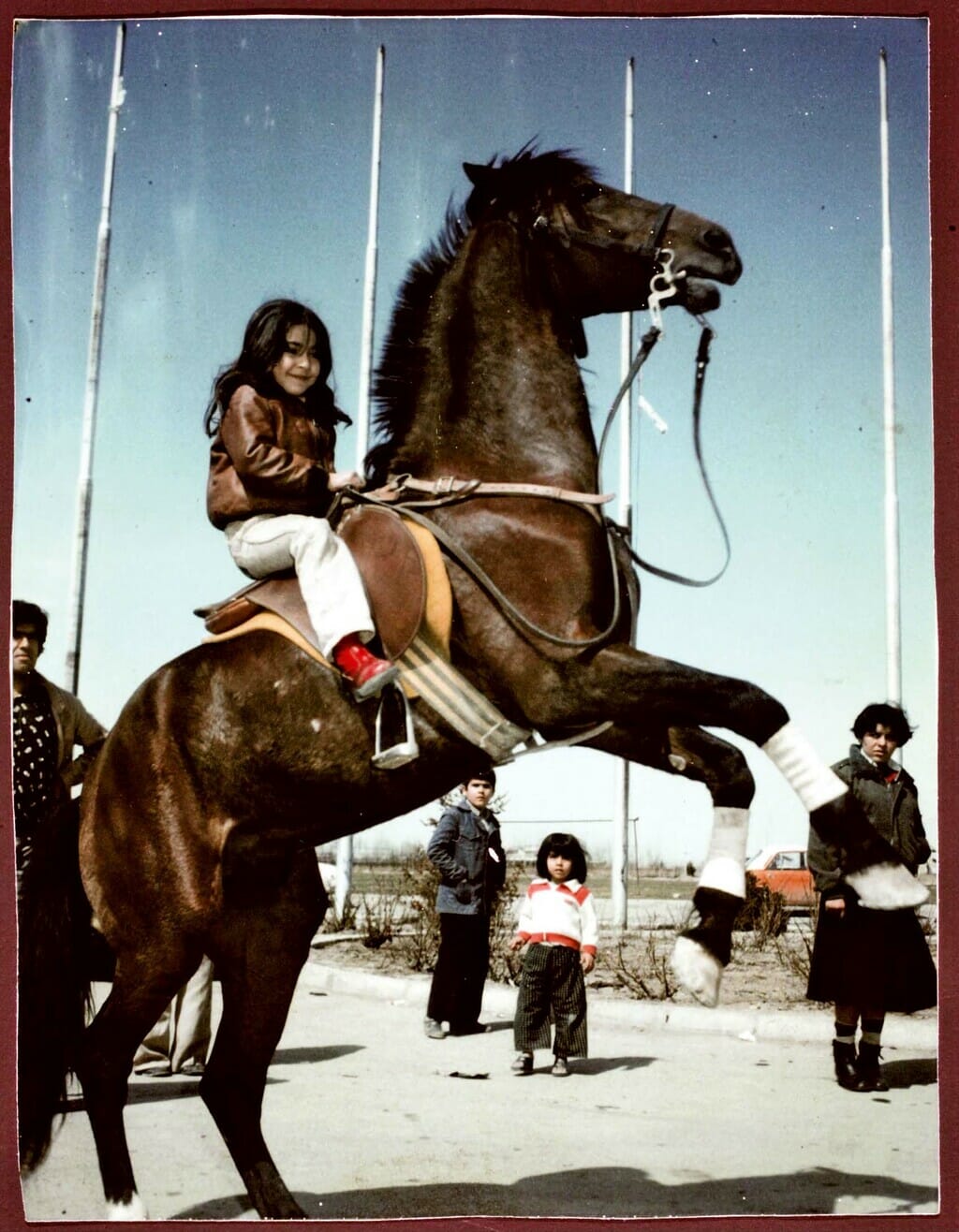

So Gilda took me back to her past, to the Tehran in which she was born in 1973, and where she grew up. To a point in her life when the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was still in power and their society was ethnically and religiously diverse. When women were freer and people more autonomous.

“We had a really good life,” she remembers. “Other than the fact that my parents had their own issues with each other. I sort of grew up in a family where there was a lot of argument. My parents were such different characters. My dad was very social and liked going out and my mum was less social.”

They travelled overseas, to Europe, and domestically throughout Iran. Gilda’s was a privileged life, but one without cosseting, or innocence.

“There was no such thing as Santa [in my childhood]. You started paying attention young, especially with the [conflict between] my parents and things. I was aware of the dynamic between Mum and Dad. You start looking at your relatives, at your family friends. You start understanding [power dynamics at a] very, very young age.”

And Gilda’s family was particularly politically aware. Even as a young child she read books with a social agenda. Small books, for children, with a political message. “You see, my mother was a teacher, and I read a lot. They were all talking politics at home. As a child I absorbed it. If you are part of a musical family where everyone is playing music, then it’s just in you. It becomes a part of your subconscious.”

Gilda’s house was a microcosm of a much larger, politically aware environment. She remembers the white noise of debate going on everywhere. Discussions were happening on television; in people’s homes, on the streets; and they were heated. Iran was in turmoil. Right, left, moderate, religious factions, political factions, were vying for control, in a soup of civil discontent. The 1979 revolution was a “short revolution”, Gilda recalls. “Everyone was in the streets and people were shouting and screaming, and we were witnessing it, and next thing the Shah of Iran is gone. He was pictured crying. And we didn’t know who this Ayatollah Khomeini was.”

From the partisan confusion emerged Ayatollah Khomeini, a relative newcomer to the scene, according to Gilda. Her family had heard his name mentioned in articles when they were holidaying in France, but not before that. Overnight he was a household name, pumped up by propaganda like a larger-than-life dictator from North Korea or China. Everybody was talking about him. He seemed to be backed by the United States. The Western media’s “mixed messages” played their part in his rise to power, Gilda believes.

“People were happy,” she remembers, after things settled down, “but it was a kind of gloomy mood, coming from a very controlled place. There was a lot of rubbishing of the previous government and a lot of promises of what was to come.” But the result was much more restrictive than most women would have hoped for.

“Within a month they started talking about the hijab. That the women should be wearing hijab and [the new regime] began putting pressure on the person who was responsible for implementing the rules that women should go back to Islamic conduct.

“I remember women I knew – well-educated women – they all went into the streets. There was a huge uprising of women. It was a revolution, and it was about equality . . . There were huge numbers of women, just women, [shouting] we didn’t do this revolution to be treated like second-class [citizens]. We did it for equality.”

Within six months the supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini said, “We do not tolerate these non-Islamic appearances.” The hijab became compulsory in every sector of public life. Women could not teach, work as a public servant, or continue any significant role in society without wearing a hijab. Ultimately, this would be extended to include every action and movement beyond the home.

“It just happened like that… my cousins and my mother had to wear the hijab. It was occurring all around me.”

Then began the separation of men and women. “So, men had to use a different bus, or [men and women] couldn’t sit together. It was 100 percent segregation.”

The Iran-Iraq War, which began a year after the revolution only served to cement the loss of human rights. Sacrifices were now expected to be made by everyone, in defence of Iran. Gilda remembers a huge convoy of teenage boys and young men sent off to fight in huge transporters, and coming back to Tehran, bombed and in bits. Human remains returned on such a scale that the body parts had to be housed in a huge stadium, until they could be returned to grieving families. “They just gathered any pieces together with a soldier’s tag and handed them over.” Gilda didn’t see what was happening in the stadium, but she said she will never forget the stench of decomposing bodies that hung over the city. “It was just terrible.”

She also saw the results of the Halabja massacre, “because it was shown on television.” Mothers clutching their children, standing atrophied like statues. “It was the nerve gas,” she explains, with some urgency, probably because I was struggling to imagine what that might look like. “It freezes people in whatever position they’re in.”

“You mean, like people caught in the ash of the Pompeii eruption?” I ask.

“Yes, but this is not empty casts, this is the people themselves.”

The chemical attack on Kurdish people in the final days of the Iran-Iraq war was the conflict’s closing horror. This mass killing is one of the biggest chemical weapons attacks on a civilian population in history. Up to 5000 civilians were killed, and an estimated 10,000 injured. Not to mention the proliferation of cancers and birth defects.

“Because we were being invaded,” Gilda remembers, “people stopped questioning. The war went on for eight years and during those eight years they used [it] to completely breach our autonomy, our human rights. If you said anything you were disrespecting the blood of these people, their families, and the Supreme Leader. They used war to justify everything.”

After the conflict ended, people who began questioning the narrative were purged.

“They just killed anyone who opened their mouth.” The regime had the authority to enter homes.

“Every day, five times a day, they could check every bedroom and make sure you’re not eating too much or drinking [alcohol]. They went into houses and broke their musical instruments.

We watched it happen. Dancing and having fun very quickly came to an end.”

The government controlled every aspect of social and political life, using fear and anxiety to suppress any resistance.

“It’s the uncertainty of it.” The unsure ground. The never knowing.

“Someone, even a private citizen, or a policeman having a bad day will come, will beat you, will take you to jail,” Gilda says.

“Cases happen every day. It is psychological warfare. Men are witnessing it, but they can’t say anything because they will be killed too. It is injustice in every possible way.” Gilda pauses.

“It’s hard for you to imagine what it is like,” she says, meaning me (and to be honest, she’s right). “You guys are secular, your justice system [stands] on its own. It’s based on human rights. But in countries like Iran and Afghanistan, our justice system is 100 percent based on a religious book and what the clerics have to say. They [have] absolute control. Women are property. Women have no rights. Women can be and should be subject to abuse and rape by their partners, and it’s okay to beat your wife. There are rules on how to beat your wife; how to rape your wife.”

But the abuses do not end with women. “They hang people for being gay, for being trans. Like this guy last year. A 20-something-year-old guy, and his cousins cut his head clean off and left it under a tree because he was going to escape Iran to go to Turkey with his boyfriend. And fathers who behead their daughters. They get maybe two years jail time, which they only serve a short percentage of. Because it is a crime that they have done based on their religious belief. [The courts] are very lenient [with them].”

Gilda believes, overall, the conditions are far worse for women than they are for men, “in terms of our autonomy and basic human rights, and just the way women are looked at. It’s a very chauvinistic ideology that they are implementing, and it has been since its inception.

“And it’s just getting worse and worse. Women can’t be judges, all [the decisions] are made by men.”

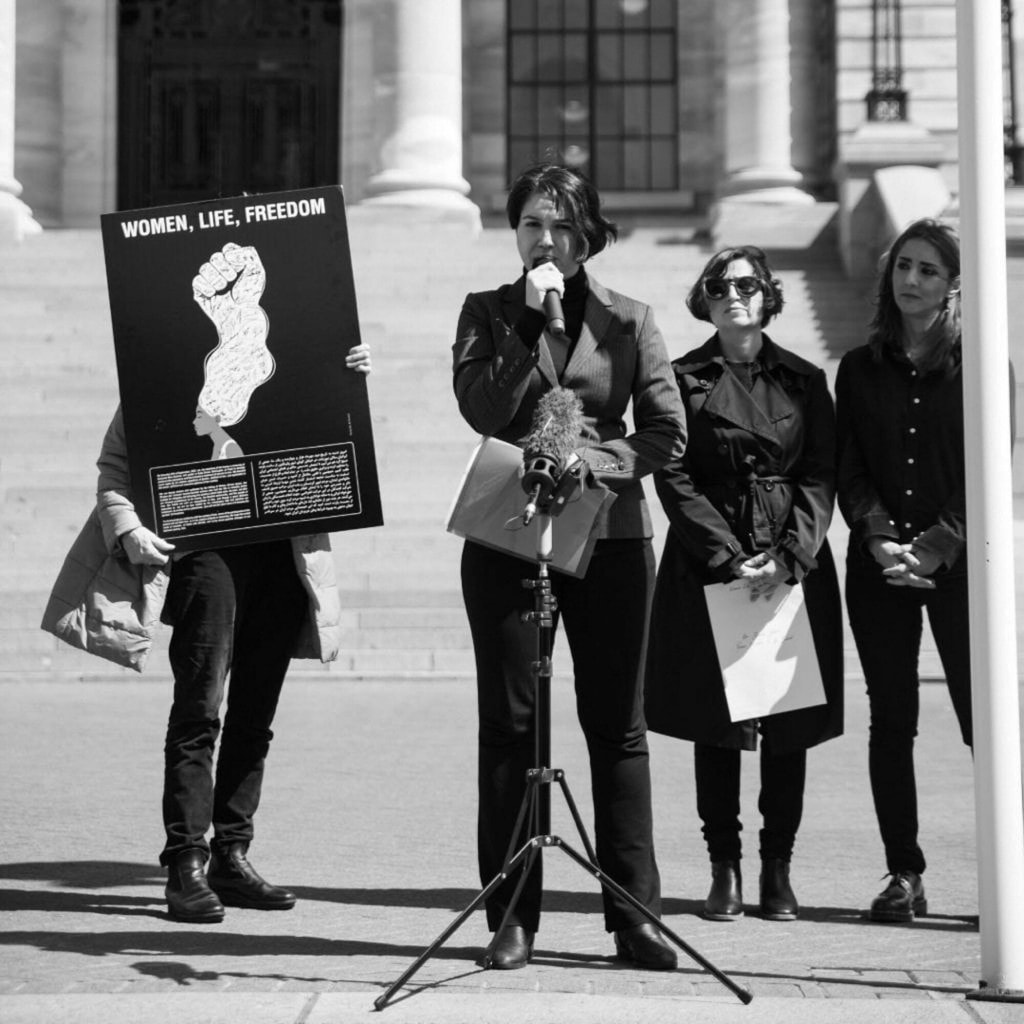

Many people around the world have been showing solidarity with the protests happening in Iran.

So, Iran’s second revolution, the one in which Gilda invests her hopes for Iran’s future, is no surprise to her. Gilda believes this revolution is much bigger than its catalyst: the tragic death in custody, on September 16, 2022, of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini. Or the feminist slogans that are being bandied around. “This has got nothing to do with feminism. This is about a girl that got murdered, but since then 25 or more other girls have been killed and hundreds of men, every day. [This revolution is about the] 14,000 political prisoners in jail.” It’s about justice, civil rights and personal autonomy. It’s about the separation of religion and state, so that Iran is not ruled by a theocracy anymore.

“It isn’t about, ‘I don’t want to wear a scarf’, or ‘I want to wear a mini-skirt’. [The hijab] is a symbolic tool of oppression. That is what they are trying to get rid of. Because we believe, firmly, that it is a visual stronghold that [the regime] can have over people.”

Gilda says, “The cat is out of the bag and it will never go back.” Women are out on the streets again protesting.

Iran has a young population. Of its 80 million citizens, the majority are young people who have been nurtured by parents who remember better times, and they are informed by the internet. And this uprising will not be repressed. “The words that are coming out of their mouths [are targeted] at the foundation of [Iran’s] judicial system, at the fundamentalists that are protecting the regime, at terrorist groups [protected by the government]. They want secularism. They are done with one religion over all people.”

I ask Gilda what she has been doing to help the revolution. She tells me that in the past 50 days, “I have been in touch with Iranian people that I know here, and talking to them, and going to protests. And I have been in touch with people in the USA and Europe asking what their governments are doing? And what our diasporic community is doing across the world?”

Gilda is heartened. “I have never seen the Iranian community come together on such firm ground. Across the world: in Sweden and Norway, in Germany and Canada, in Australia . . . it’s everywhere. Different cities, [all coming together with one voice] to demand the same thing. It is freedom for Iran from the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps), and the expelling of the ambassadors of Iran across the world, because they are an extension of its government. By not condemning the Iran regime, by not declaring the IRGC a terrorist entity . . . you’re just supporting them.”

So, Gilda went ahead and did what she could in New Zealand. “I put these billboards up, which were simple [in their communication]: ‘Freedom for Iran and no IRGC’.”

Edmund Burke is credited with the famous words, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good [people] to do nothing”, and this is more or less Gilda’s mantra. She will do whatever she can to raise awareness of the abuses in Iran.

Gilda realises that not everything she has to say, on the subjects of Iran and the hijab, are universally welcomed. But it isn’t in her to give up on a country and a people she loves. She believes the responsibility to support this revolution for civil rights is as much that of the Iranian diaspora, and their host countries, as it is of those on the ground in Iran.

She admits, therefore, to finding it very triggering when she saw Jacinda Ardern projected, dressed in a hijab, on Dubia’s Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building. Her response is not a diminishing of the horror for what happened in the two Christchurch mosque attacks on March 15, 2019.

“We all felt awful for what happened. Imagine leaving your country to get away from all that [corruption and control] to come to a free country, and you are minding your own business and you have that happen to you. It’s just terrible.”

No one can extinguish the awfulness of this event. Nor is Gilda’s stance an undermining of the hijab for devout women followers of Islam. She believes everyone should be able to worship the way they like, and their choice must be respected.

Her problem is that the hijab is a symbol of the oppression of women in Iran. If Jacinda Ardern had worn it in a mosque, then it would have had a genuine, religious context. But to wear it on New Zealand soil, in secular spaces, is as much an endorsement of terror as it is a statement of compassion.

“I was reading comments online,” Gilda says, “and there were all these people that were highly religious, writing things like, ‘more Western women should follow in her footsteps’ – everything [and every gesture] has a consequence, right?”

Then she tells me the story of CNN international anchor, Christiane Amanour, who was instructed at the last minute by Iranian President, Ebrahim Raisi, to wear a hijab as a “matter of respect”. She politely declined his conditions and the long-planned-for interview was canned. It took her years to decline them, but finally she refused. Gilda sees this as a victory. A stand of resistance by a senior member of the media.

Gilda’s words to Western leaders are these: “If you hadn’t cooperated with these people [by wearing the hijab], they would have stopped this behaviour a while ago. [Religious hard-liners take great satisfaction in the fact] that they have the power to put a scarf on a Western woman in her own country. Western society is responsible” – for endorsing persecution, when it is compliant.

Gilda believes the hijab is a taboo subject in the West. An awkward distillation of “woke”, or politically correct sentiments that hover over a wasteland of ignorance and indecision about the hijab. And I can’t help but agree with her that we in the West need to talk and know more.

PHOTOS: LUKE HARVEY AND GETTY IMAGES

Women, life, freedom

Protests have been happening around Aotearoa since the death of Mahsa Amini.

Like millions of Iranians who grew up after the Islamic revolution, Samira Taghari endured events that have left a shadow over her life.

As a law student and young professional, she personally witnessed hangings, a fatal stoning and the lashing of several people. A close relative of hers is among the thousands of people killed under the current regime. Samira has been an active political protestor here in Aotearoa but fears for the Iranian diaspora, believing there are several defenders of the Islamic regime in New Zealand who are feeding intelligence back to the regime, which in turn targets family members still living in Iran.

“I do worry about family safety,” Samira says. “But that’s true of everyone who stands up to this cruel regime – particularly the heroes fighting for freedom right now on the streets of Iran. They have to worry greatly – about themselves and then also about their loved ones.”

She wants the New Zealand Government to take a strong stand against a regime which sanctions sexual abuse and torture.

Elly Stone, who came to New Zealand 26 years ago, is among the women who have joined the protest.

“We are fighting about very basic human rights. It’s not about religion or wearing or not wearing a headscarf, it’s just about choice and about having the same rights as anyone else.”

When Hana Habibi, an economist working in Wellington, stood in front of parliament and cut her hair, it was a symbol of grief and rage. Grief at what is happening in her birth country. Rage at the lack of urgency with which the international sanctions are working.

“Iran has successfully portrayed itself as a country with whom you can negotiate,” she says. “The regime is sophisticated and has learned how to lie. How can you have human rights negotiations with a country that systematically engages in discrimination, against ethnic minorities, religious minorities and gender minorities?”

What Hana and the protestors want are targeted sanctions – sanctions against the individuals who are directly involved in the brutal crackdown of protestors. Targeted banning of these individuals.

“We want the expulsion of the ambassador in this country because by having an ambassador here we are providing a platform for the regime. And this is intolerable to us,” she says.

“The insecurities we all feel as protestors are justified. The regime has long arms and disappearances have happened – it is something real and important.

“The only way to live in freedom and dignity is for the religious theocracy to be replaced by a democracy where people can live freely, choose their lifestyle. New Zealand cannot afford to be complacent.”

TEXT: SUSANNA ANDREW

PHOTOS: HANA HABIBI