A Melbourne writer’s debut that explores what it means to lose a parent, a Kiwi’s wilderness adventures, and an Irish tale about doing the right thing.

Sunbathing by Isobel Beech

Can a novel be unrelentingly sad, deeply intelligent, and still suffused with an ethereal beauty and goodness? It sounds impossible, yet Isobel Beech’s debut Sunbathing can be described this way.

A young woman, reeling from the sudden death of her father, escapes Melbourne and the realities of her life to go and live with friends Giulia and Fabrizio in the Italian countryside in the months before their wedding. The novel unwinds as the woman speaks directly to her father, detailing not only the flight to Italy and how she fills her days with Giulia and Fab over the long hot summer, but also with reflections on the final months she spent with him before his death. In her mind, she can say to him all the things left unsaid.

Her days in Italy fall into a simple, honourable routine: watering the vegetable gardens, eating at the table outside under the trees, walking to the village for supplies, filling the bottles with water to keep cool in the fridge, and feeding the stray cats. She finds incredible solace in the gentle, tender domesticities of life with her friends,

a quiet place of solitude and companionship both, where she has the opportunity to process her grief in her own time, as well as put it aside to continue her life. But through it all, there’s her phone, and she battles a silent war to understand her addiction to social media.

Sunbathing is a quiet exploration of what it means to lose a parent, and to lose them by suicide. With this loaded subject matter, Beech accomplishes an incredible acrobatic dance between lightness and heaviness. The writing is steady, unpretentious, but lyrical. It’s familiar, as though a friend is speaking to you, but with the odd shy joke, the honest appraisal of anger and anxiety, and the earnest yearning for love and admiration. There are strong echoes of the unique voice and attitude of Meg Mason’s Sorrow and Bliss, that same unflinching stare at the hard parts of life through the eyes of someone young and female, someone who spends a lot of time online.

Beech dissects “influencer” culture, toxic masculinity, the true meaning of friendship and the ways in which we can fail each other. Her protagonist recalls heady dinner parties where discussions of #MeToo spiral into pettiness, and the hollow virtue-signalling of Instagram celebrities. This all contrasts with the sweet wonder of friendship lived in “real life” and the irreplaceable glory of the world beyond our screens.

This is a graphic portrait of loss, and a glimpse of the struggle to continue in the shadow of regret. Beech’s character inspects grief with a clear eye – “it’s clumsy and inconvenient and you may well come to hate what it turns you into – inarticulate, cagey, vague, selfish, moody, paranoid”. She writes with nuance and gentle care, though, about suicide, providing more than a clichéd glance at this tragic devastation. I found the subject matter intense, but when I finished reading this book, all I could think about was the hope and beauty portrayed alongside the sorrow.

Do you need someone to talk to? Support is available from Lifeline on 0800 543 354, or call or text 1737 to talk with a trained counsellor.

Solo: Backcountry adventuring in Aotearoa New Zealand by Hazel Phillips

In 2017, journalist Hazel Phillips was tired of Auckland – expensive houses, miserable traffic. A new job based in Sydney meant she could work remotely, and her colleagues in Australia didn’t know if she was working from a Department of Conservation hut or from a living room in the city, so she took the opportunity to live “strategically homeless”, moving around the country at leisure, spending her free time mountaineering, tramping, and experiencing the wonder of our incredible islands. Solo is about her time living as a nomad, but it’s also a fascinating insight into the history of our adventuring nation and the men and women who walked the hills before her. Solo is part history and part New Zealand’s answer to Cheryl Strayed’s Wild. Full of photographs and beautifully designed, this is an absorbing read.

WIN! We have three copies of Solo to give away, thanks to Massey University Press. Email [email protected] with WIN SOLO in the subject line, tell us your name and postal address and you’ll be in the draw. Entries close on July 31, 2022.

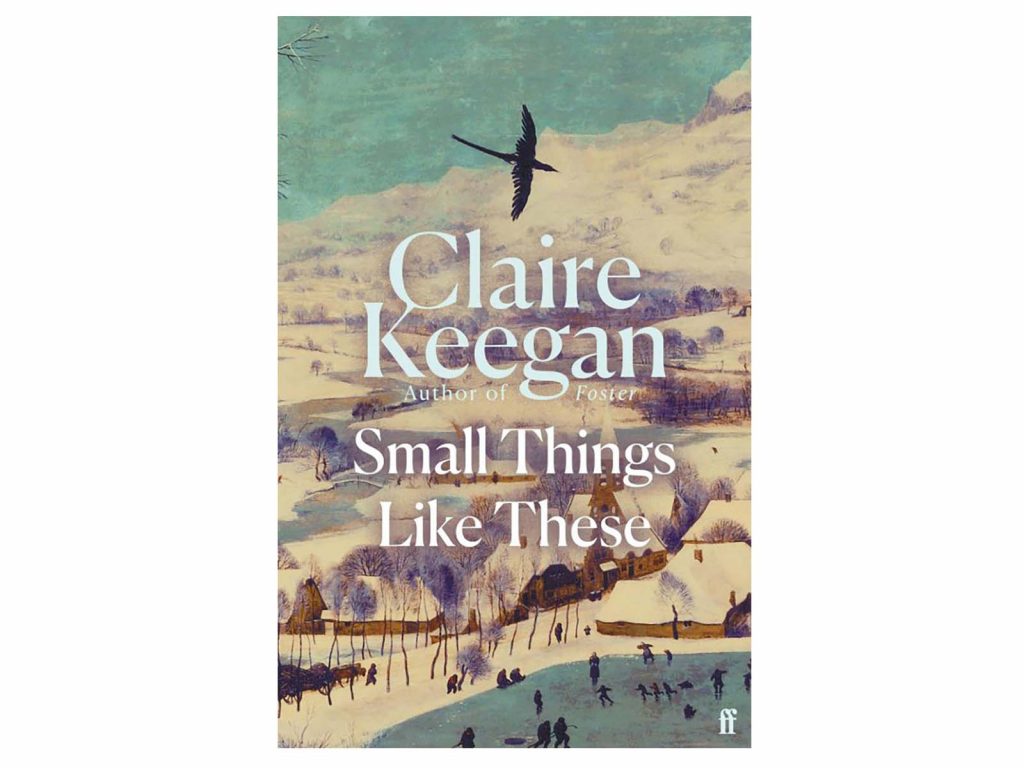

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Irish writer Claire Keegan’s long-awaited new work is a tiny, almost perfectly formed novella. It’s 1985 in New Ross, County Wexford. Bill Furlong, a coal merchant, married with five daughters, is busy delivering coal in the brutally cold weeks leading up to Christmas. One of his final deliveries is to the convent on the edge of town, attached to the training school and laundry, a place full of young women, a place of rumour and a shadow of disrepute. When Bill discovers a girl locked in the coal house – malnourished and in severe distress – he’s reminded of how “it would be the easiest thing in the world to lose everything”. After this encounter, he can’t stop wondering about the women in the convent. He considers alternative worlds in which things are different for him and his family, but his wife chastises him: “Where does thinking get us?”

But Bill cannot help but think. His deeply philosophical nature draws him out of the sturdy and concerted ignorance that the rest of the town, the rest of the country, is all too happy to maintain. Exploring the debt we owe others to be curious and act upon our findings, Small Things Like These is fiction that doesn’t shy away from the harrowing parts of humanity.